By guest correspondent Elisabeth Ross

A little while ago, the New York Times ran a story about the so-called “family dinner” predicament, which in this latest commentary was anchored by yet another study suggesting an association between frequency of family dinners and adolescent substance abuse rates.

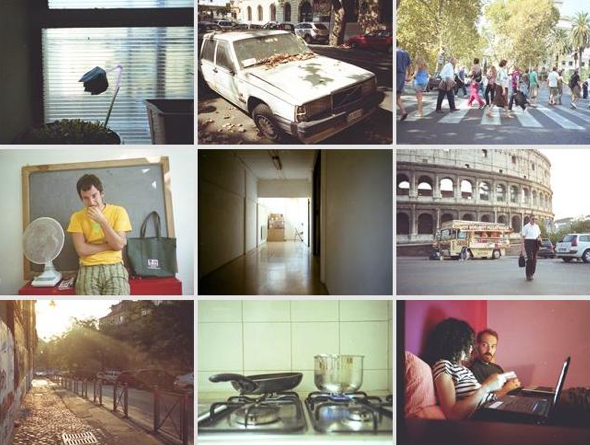

The photograph accompanying the article on the front page of the Style section forecasts the nostalgic, eternal return to that staple of the modern visual lexicon: the mid-century kitchen, complete with iconic 1950s housewife emerging to present a casserole to her adoring family seated at the table.

The faded pastels, washed out background, and dinner table floating in a cloud of whiteness suggest an ethereal quality, interrupted only by the father’s black suit. He sits slightly off balance, imitated by his son, but not quite able to project full parental authority. The smile is a little too forced. Is he nervous? Maybe he and his wife have just had a fight. Maybe he’s wondering if that casserole is about to hit him in the head. Maybe she’s looking at it, gauging just how much she’d have to clean up afterward and if it’s even worth it.

Of course, that’s not what we’re supposed to be thinking. But we have seen this sanitized domesticity performed so many times, that we should know better than to confuse the ideal with the real. The image of the dressed-up housewife in her otherworldly kitchen can be considered today in terms of underlying doubt, anxiety, and potential for transgression. In this way, the image speaks to another photograph from the same article:

In this 21st century family tableau, the mother is similarly turned inward, that is, facing her family and facing away from the viewer. Comparison with the first image is supposed to be damming: look, for example, at how the four individuals are eating junk food while strapped into seats that keep them separated from one another. But that’s not the only way to see it. The space is private but mobile, comfortable, and with modern amenities at hand. The mother–nothing suggests she is a housewife: no apron, no casserole, no husband, no house–is firmly planted in the driver’s seat. The pink apron is replaced by business-casual black. Mom’s in charge. At least, of dinner.

And that’s part of the problem.

After presenting the inverse ratio of family dinner frequency to teen drug use, the article parenthetically notes that 80% of family dinners are prepared by women (while still holding 50% of all jobs) and then features interviews with 8 women, who describe their commitment to or reluctant abandonment of the family dinner (one woman would only admit to the latter on the condition of anonymity).

Every year for the last decade or so, we hear the same statistics linking family meals to an assortment of psycho-developmental benefits for children. The data does not show causation, researchers admit, rather, simply an association. Which means that any number of variables on both sides of the equation would change the actual cause and effect outcomes dramatically.

So what is really going on here? The Columbia University authors of this latest study are also the folks who created “Family Day, ” designed to promote family dinners. (This year, it was September 28, in case you missed it). The website has a “sponsors and partners” link which, when clicked, display giant logos; among others are Stouffers, Coca-Cola, and Smuckers. And anyone who has visited a supermarket recently will have noticed a revival of food products marketed as quick and easy ways to get the Family Dinner ready.

Keeping in mind that the iconic images of 1950s housewives and their kitchens were strategically deployed to promote an entire postwar aesthetic tied to consumer spending, one should ask what such images really show and what does that have to do with reality, then or now, not to mention quality time with the kids. “I don’t think we really know what a good family dinner is,” one psychologist notes in the article. And apparently we don’t know what one looks like either.

Conjuring up 1950s iconography may work for some, but for others it is an invitation to shifting interpretations and resistance. The housewife and her kitchen should invite interrogation, not surrender. And one question to begin with might be why, in 2009, we are even suggesting that kids might be turned into drug addicts unless women conform to a model of family life that never really happened.

Photographs by Getty Images and Scott Dalton/New York Times.

Elisabeth Ross, a graduate student in the program in Rhetoric and Public Culture, Department of Communication Studies, Northwestern University, has no idea what her kids will have for dinner this evening. She would like to salute Elinor Ostrom of Indiana University on this week becoming the first woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Economics. Dr. Ostrom was not permitted to take advanced math in high school because women were routinely advised at the time that they did not need trigonometry or calculus, “if they were going to be barefoot and pregnant in the kitchen” (NPR interview, 10/12/09). You can contact Elisabeth at e-ross@northwestern.edu.

2 Comments