There are only a very few dates in U.S. history that are instantly recognizable by most citizens: July 4, December 7, June 6, September 11; for baby boomers, maybe, November 22. But beyond that, we tend to remember events more than dates; and when such events are no longer present to the collective mind’s eye they tend to fade into the dustbin of history—part of the academic historian’s palette, to be sure, but increasingly difficult to access as a usable past. Few people recall the significance of May 3rd in U.S. history. I didn’t, and I have studied and even published essays and books that speak to the momentous events of that day in 1963; or at least I didn’t recall the significance of the date until I literally stumbled upon the two photographs below while surfing the web and looking for something to write about yesterday morning.

The images were included in a slide show titled “This Week in History” and buried deep on the Camera Works page of the Washington Post beneath twenty three other slide shows on a potpourri of topics ranging from the swine flu crisis, the Chrysler bankruptcy, and President Obama’s first 100 days in office to the Kentucky Derby, a photo exhibit at the MOMA on the recent history of fashion, a retrospective on the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, the visit of an eight year old beaver to a veterinary dentist, images of animals from around the world, and the top ten sports photos of the week. As far as I can tell, nothing else in the WP commented on the events of May 3, 1963 in the city of Birmingham, Alabama, nor for that matter was the topic addressed by any of the major news outlets or agencies, including the local Birmingham News. It is almost as if the events of that day have faded from collective memory, no longer necessary to a productive and usable understanding of our nation’s bloody racial past.

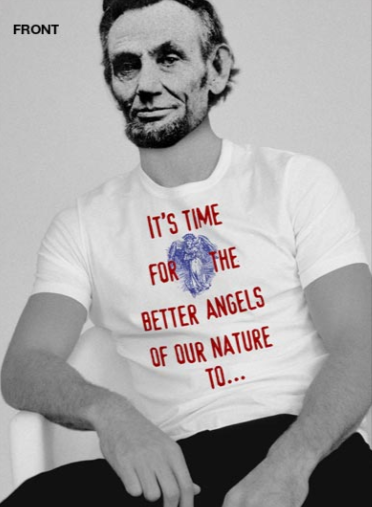

The point is accentuated some by the front page of Sunday’s NYT, which included two stories above the fold, one touting President Obama’s professorial pragmatism in thinking about the Supreme Court and the other titled “In Obama Era, Voices Reflect Rising Sense of Racial Optimism.” Replete with photographs, the later story featured polling data indicating that 2/3s of Americans hold that “racial relations are good” and illustrates the point with anecdotal data of blacks and whites “communicating” on the streets, at the gym, and so on. The article concludes with the words of an African-American auditor from Tampa, FL, “I’m not saying that the playing field is even, but having elected a black president has done a lot.” It would seem as if we have moved beyond the days of Bull Connor and the KKK; and if so, maybe it is time to let the images of water cannon and attack dogs fade into the recesses of our collective memory as the nation heals its wounds and moves forward.

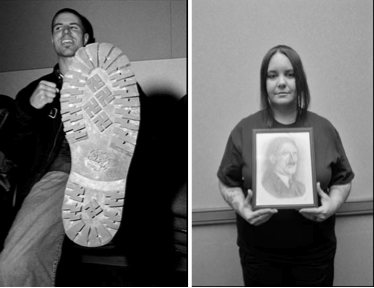

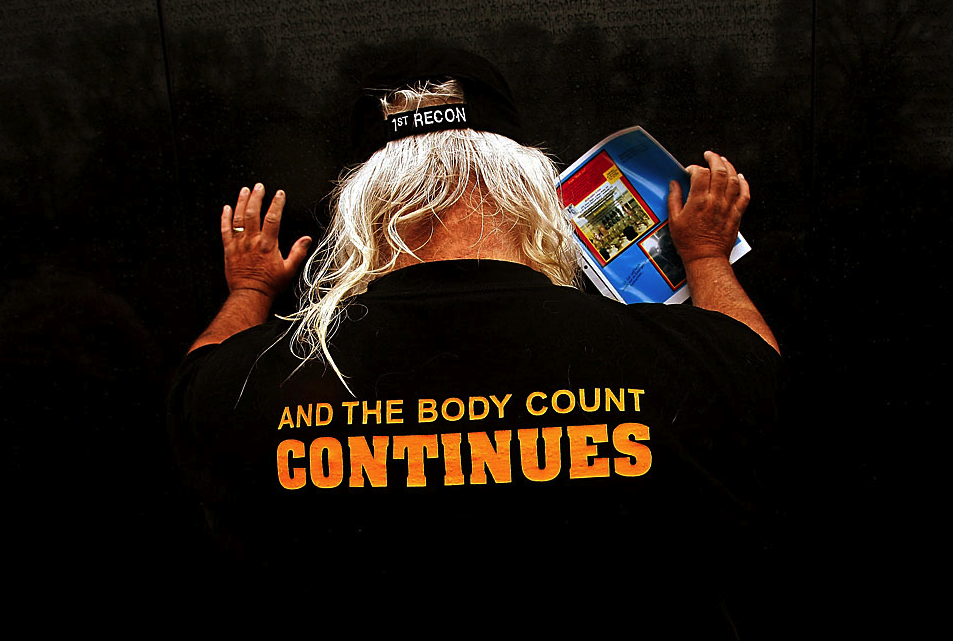

Or maybe not … for buried within the NYT article is the report of statistics from the Southern Poverty Law Center indicating that there has been a 50 percent increase in the number of active hate groups in the U.S. since 2000. The Times barely recognizes the point, concerned more with the “sense of racial optimism,” but the significance of those numbers is underscored in last week’s edition of Newsweek, which repeated them as part of a feature story on the recent “rebranding” of white supremacist groups as “mainstream” political organizations. The online version of the article was accompanied by a slide show of images such as these:

What is disturbing about these photographs is not just that they put hateful symbols on display, but that they are happily posed—and by young people, the next generation of Americans—without the hint of public shame. Indeed, it is no stretch to imagine these individuals proudly posting these images on social networking sites like Facebook or You Tube with full expectation of their viral dissemination.

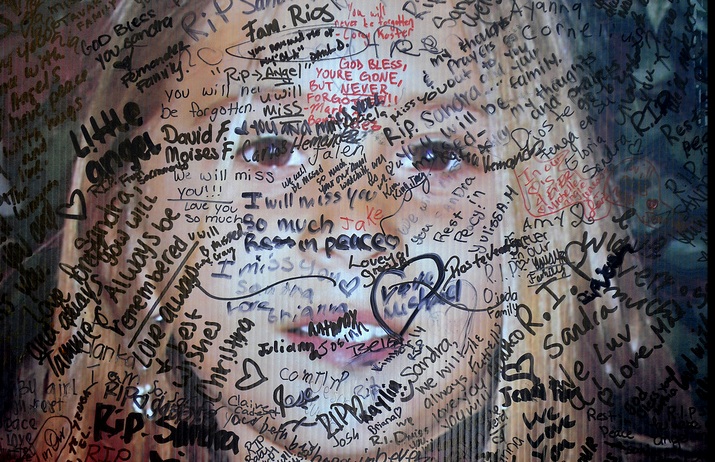

Walter Benjamin says that to “articulate the past historically” means to “seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger” and thus to recollect the present (and one can only assume its implications for the future) in relationship to a prior moment in time. To fail to do this, he suggests, is to take the risk that “even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins.” I would like to think that the election of President Obama has put an end to the American Tragedy of racial discord and set the nation on a trajectory to an ever hopeful future. I would like to believe that we could securely tuck away the photographs of May 3, 1963 or to recall them with the same simple curiosity that leads me to wonder about Frank Lloyd Wright’s architectural genius or the dental problems of aging rodents. I worry, however, that if we fail to articulate our image of President Obama’s election with our images of that fateful day that we do a grave disservice to ourselves and to the safety of future generations of Americans – and more, to the many who gave their lives in the name of racial justice.

Photo Credits: Charles Moore/Getty; Bill Hudson/AP; Bruce Gilden/Magnum and Newsweek