A great deal of heat was generated over the Bush administration policy of censoring photographs of military coffins being returned to the US from Iraq and Afghanistan. (Actually, the policy had been in effect since the first Bush administration in 1991, but it was renewed by W. The policy was changed in December 2009.) The criticisms were justified, of course: democratic governments are supposed to be transparent; wars should not depend on public ignorance of their costs; military sacrifice can not be properly honored if hidden. On the other side, defenders of the status quo had argued that the images would fuel controversy about the war.

Now that the coffins are back in public view, however, the impact of the photographs seems to be far less than anticipated. (Some day governments will learn that the best strategy is to hide things in full view.) In fact, the result has been a big yawn. That may be why photographers now are doing something far more interesting that playing supporting roles in a conventional standoff. Instead, we are being shown something else.

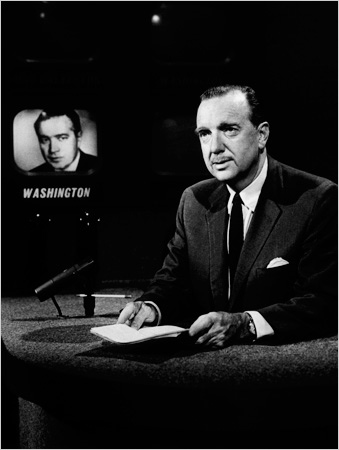

This image from the UK is, not surprisingly, a model of ritual observance. The coffin of a rifleman killed in Afghanistan is being carried to a hearse during a repatriation ceremony at RAF Lyneham in Wiltshire, England. The flag-draped coffin forms one point of a triangle completed by the enormous transport plane centered in the vanishing point and the hearse in the left foreground. (The vectors are marked by the line on the tarmac, the wing/coffin and tail/two figures standing at attention.) The set also composes a rectangle as the plane appears to be the same length as the distance between hearse and coffin. The rectangle creates a strong sense of order and stability, while the triangle directs the meaning of the event from the foreground on earth through the plane to the blue sky beyond.

Thus, the photograph completes the work of the ritual practice being depicted. The viewer is being asked to acknowledge two transitions: the soldier’s remains are being brought from a foreign battleground back to the motherland, while his soul can be imagined as already winging its way from earth to heaven. Fittingly, the coffin is neither in the plane nor the hearse; the soldier is neither completely within the institution of the state nor transferred to the family. He is now forever in between and somewhere else. The institutions remain, here in idealized form: the large, impersonal, powerful plane that is nonetheless beautifully self-contained and standing at ready, dedicated to service of the individual citizen; and the small, familiar vehicle is also beautiful because built to human scale, carefully polished, designed to handle loss, and part of everyone’s fate.

Obviously, that story is too good to be true. Rituals are not merely fictions, and they don’t contain only good news. What struck me most about this photo is not the precise positioning of the ritual objects but rather the terrifying isolation being displayed in plain view. Note how nothing is connected except by the invisible vectors of visual design. Each element of this social setting stands in complete separation from the others–including the viewer from the scene itself. In place of any connectivity, we see the open tarmac, flat landscape, and immense sky. You can imagine heaven, just as you can imagine the nation, but the photograph also suggests the the story of this death is radical isolation. That soldier is forever separated from those who knew him, and that loss contributes to greater separation among all those within the community.

Nor is this the work of one photographer, or a British rather than American tableau.

This photograph is from Delaware, probably at Dover AFB. A Navy team stands at attention before a coffin that has arrived from Afghanistan. Here you see basic elements of the military ritual in the first photograph, albeit in much more humble fashion. The coffin is partially hidden, the state how is represented by a delivery van, and the sailors’ service uniforms suggest a working class destination. Most important, however, is that we again see human isolation amidst a vast emptiness. Here, in fact, that comprehensive absence can’t be contained by ritual forms. The scene is, sadly, all too revealing.

Perhaps this is the real challenge of showing the coffins. The basic question is not whether to criticize the war or support the troops, but rather how to cross the distances that already separate everyone in the human community.

Photographs by Adrian Harlen/Reuters and Mark Wilson/Getty Images.

2 Comments