Among the sophisticated, raison d’état (“reason of state”) is the first principle of foreign policy. Decisions are to be made on behalf of the national interest without regard to confounding values. So it is that democracies can support dictators, to take one example that might apply to U.S. foreign policy now and again. Although the idea has been the subject of extensive debate, it has at the same time become ever more deeply embedded in practices of state administration. It should not be surprising, then, that those practices acquire the look of rational, efficient mechanisms of control.

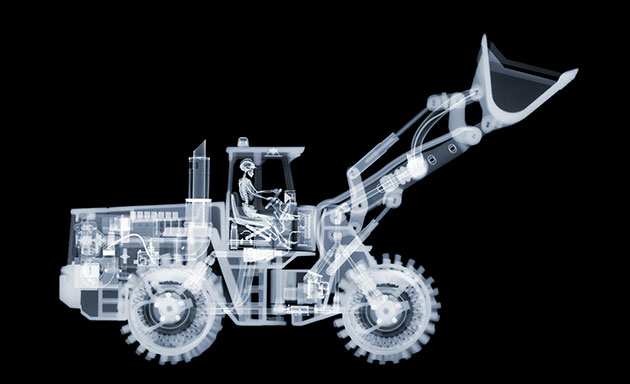

This photograph of a common room at Guantanamo Bay prison is a study in rational organization, everything in its place. The room is used for activities such as watching television, but its real purpose is obvious: maintaining comprehensive control of the inmates while they are out of their cells. And, yes, those are leg irons on the floor; the prisoners are locked in while sitting at the table. The photo may be intended to feature the functionality of the room: containment appears almost transparent–no dungeons here–while the asceticism and cleanliness double as substitutes for morality.

Modern regimes of control rely heavily on assumptions about reason and necessity in the use of power. They can’t be less powerful or more moral, we are told, because the rational consequence will be that a more powerful and less moral opponent will triumph. They can, however, apply instrumental rationality and modern technologies to maintain security, and that competence becomes sufficient justification for administrative sovereignty. If they can’t be moral, democratic, or otherwise defined by anything other than the use of power to maintain security, at least they can be systematically organized to achieve their one objective.

Fair enough, but for one problem. The result of this mentality has been not the enlightened use of reason, but rather ever more well-financed stupidity. Massive expenditures on prisons don’t reduce either terrorism or crime. Funneling billions of dollars to dictators doesn’t build states or economies, but instead wreaks civil society and produces great swaths of poverty and dependence. Trammeling democratic values (and others as well) doesn’t win hearts and minds while it does feed cynicism and hatred. But we knew that. And that knowledge doesn’t change much, in two senses: it hasn’t influenced those in charge of the state, perhaps because it hasn’t itself become more insightful or articulate.

I want to suggest another, perhaps odd approach to the problem of state stupidity. Let me ask, when can we see stupidity? Would we know what to look for? This is not a matter, at least for the moment, of defining the term, but rather of considering how behavior and practices known to be stupid can be seen as such. The culture provides a few cues: some, such as slapstick comedy may not be too helpful unless analyzed rather than simply applied. Other sources such as Kafka’s Trial and Castle might be important sources, but they are highly literary rather than directly visual.

I’m running out of time, but as I look at the photograph above, an architecture of stupidity begins to emerge. For example, the extreme functionality of the space that actually inhibits any reasonable use, much less any use that might lead to resolution of the larger conflict. Also perhaps the overdesign of the security apparatus: tables bolted to the floor within a cage will have their rationale, but there is something so excessive here that it has to be a sign of arbitrary rules, endless procedures, and near-complete inattention to anything else but the literal replication of the machinery of power. Nor is that a dynamic process, but one that depends on stasis, on the inactivity, boredom, and habitual resignation to routine evident in the guards’ postures.

The prison is a monument to stupidity. It is not enough to reform the prison, however. My point is that the national security state produces stupidity because it depends upon stupidity. The national interest of a democratic people may be served well by reason, but the modern state, to the extent that it is a regime of coercive control, will rely on another mentality: stupidité d’état.

Photograph by Tim Dirven/Panos Pictures.

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes.

1 Comment