The bomb scare in Times Square the other day was a close call, otherwise known as dumb luck. And despite the embarrassment of the would-be bomber coming from Pakistan rather than Iraq or Afghanistan, one can assume that the scare only helped to continue the American war effort. Whatever happens in the US, the bombing is sure to continue over there. Rather than make light of the association between actual terrorism and US military campaigns, it might help to ask if coverage of the two might have more in common than has been noticed.

The New York Times slide show was labeled “Bomb Scare in Times Square,” and the caption for this photo said, “A crew cleaned up at the scene.” As if: I don’t see either a crew or Times Square, but rather a lone functionary in a back alley scene out of some sci-fi movie. Body Snatchers II, perhaps. In fact, the photo is a study in disconnects. Instead of the spectacle of Times Square, we see stacks of garbage, shipping flats, and other odds and ends. Instead of workers, there is one figure in an entry-level moon suit, and rather than cleaning up he seems to be merely rearranging the shards of glass with that ridiculously small broom. In place of terror and mobilization, there is this strangely esoteric ritual. Rather than war, there is a choreography of forensic sanitation (note his mask, gloves, and slippers). While some speak of the defense of civilization, this scene is vaguely surreal, and in lieu of the destructiveness of a powerful explosion, there is only broken glass on an empty street.

But there wasn’t a powerful explosion, so what’s the point? What I want to suggest is that the disruption produced by the non-explosion reveals some of the blindness that now regularly accompanies US attitudes toward war. The first problem is a failure to recognize the vast difference between the rhetoric of the war on terror and the banal realities of how it actually operates. Civilization comes down to picking up the garbage, and its defense usually depends more on a well-functioning civil society and basic police work than on the projection of military power across the globe.

A second problem is that we don’t see the either the bomb or the likely retaliation, but only a trace of destructiveness and an innocuous figure of state action. In this case, the lucky break of non-detonation excuses what is a regular practice of omission. Despite some outstanding documentation of the effects of war in Iraq and Afghanistan, the US public an never see more than a a small fraction of the destructiveness caused by American military bombing, and then only from a distance. (Assessments of total direct and indirect civilian deaths in Afghanistan due to US military action range from 8,768 to 28,360.) Let me be clear: powerful documentary photographs are published in a few outlets, but not enough and without the full reportage needed to really make a dent in public opinion.

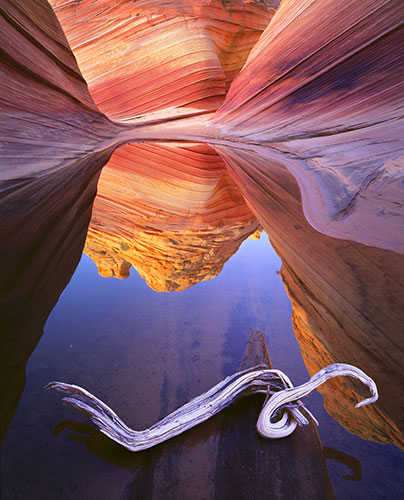

And what documentation of military destructiveness is available is balanced by images such as this one:

This image of a Marine Harrier jet would seem to be the opposite of the one above: a member of the ground crew has just finished fueling the sleek, powerful machine, which stands at ready on a clean runway against a backdrop of efficiently arrayed support buildings. This is a picture of preparedness, and of the awesome capability of the American military. There is nothing hapless about it, and we seem on the verge of action, not stuck in the dismal aftermath of having been attacked. That is the message, of course, and so the one image counters the other: they may have car bombs, but we have this. They may be able to pull off an attack, but there is no doubt that this machine is built for serious payback.

That said, I also think that the two images are both part of the same pattern of willful obliviousness. Look again at the second photo: once again, there is only the trace of the bomb’s destructiveness. (If you look carefully under the wings, you can see some of the weaponry.) Although now seeing what comes before an attack rather than what remains afterward, the attack itself is not to be seen. Even the style of the image, with its modernist aesthetic of sheer surfaces, clean lines, empty space, and other design features of modern technology admits of nothing messy, bloody, or deeply hurtful. There is no sense of how the bomb will disrupt Afghan society–or, for that matter, how the expense of maintaining the jet and all that goes with it is disrupting American society.

The authorities rightly whisked away the SUV that was supposed to detonate in Time Square, and surely this Harrier jet will have flown another mission since the photograph was taken. In each case the photographer has documented one scene in a global war that is all about bombing and being bombed. But in these photos, as with so many others, the bomb, one way or another, isn’t there. About that one might ironically remark, “bombs away”; or, perhaps, “out of sight is out of mind.”

Photographs by the New York Times and Tim Wimborne/Reuters.

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes.

0 Comments