Disasters often provoke “finger pointing,” fault-finding, recriminations, and other accusations of failed responsibility. As well they should. Those who complain about “politicizing a disaster” usually have something to hide, and spirited public discussion of possible causes is essential for better preparation and improved response. Even so, preoccupation with what did or did not happen before and during the event can lead to a missed opportunity. Disaster photographs can contain hints of how the present contains within it alternate futures: suggestions, that is, of how present tendencies could lead to catastrophic conditions. Those outcomes are not caused by the disaster, but they can be exposed as the smooth surfaces of a civilization are twisted into wreckage.

This photo from Tuesday’s blizzard is a lovely example of what I have in mind. The crumpled SUV is positioned in front of Chicago’s magnificent skyline, as if the vehicle were a harbinger of things to come. The wrecked car is one small example of the civilization symbolized by the tall buildings: all are miracles of metal and glass created by the industrial technologies now exposed to the elements once the car’s skin has been sheared away. Of course, we are aware of the difference in scale and realize that the car can be towed away without loss to the urban core, and yet: could the city be more vulnerable that it had seemed? Could the car and the city share not only a common environment but similar fates, different only in the time it takes for the entire society to collide with an increasingly harsh environment?

The more I looked, the more I realized how other photos were making similar suggestions. This image of a long line of abandoned vehicles on Lake Shore Drive could be right out of a science fiction movie. Somewhere between Victorian ideas of “heat death” and a dystopian future of abandoned cities, this image once again positions the disabled vehicles on a line toward the still illuminated buildings in the background. Nature is clearly winning, however, and it is easy to imagine the feeble street lamps winking out and the climactic pall becoming ever more deadly, smothering everything at last.

The movie can’t dwell on panoramic shots, however. We have to move in closer to get the real feel of decline and death. This image of snow drifted into a bus does that very well. We can imagine people once filing in, sitting, standing, and jostling as the driver navigated through traffic, and yet we can see only cold, inert abandonment. Returning to nature, but not for organic regeneration, this is a scene of icy metal, useless equipment, brittle decay. The door stands open, but no one wandering through would stay. The snow is like desert sand, and this place has become a ruin.

Life would continue somehow, of course, but Beware the Prong People. This image of a rescuer on a snowmobile will have brought relief to those trapped in the blizzard, but it can double as an image of a predatory nomads. Morlocks on ice, Mad Max in the snow, whatever the allusion, the yellowish miasma of snow, fog, glare, and swirling winds suggests a hideous world where cyborg killers can prey on those already weakened by the unending storm.

Surely, however, it can’t get that bad.

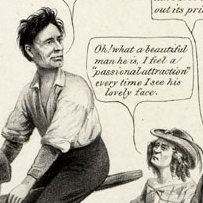

If Blade Runner had been shot in Chicago in the winter, it could have looked like this. But don’t feel too sorry for her. She’s got her goggles and her Bud Light, and one person’s blizzard is another’s party. This could be a study in individual improvisation or in gradual cultural adaptation to a steadily deteriorating climate, but it doesn’t have to be so bad. Her stylish insouciance in the face of the storm is charming, and one is reminded that the young often don’t know enough to cynical, which benefits us all.

A blizzard in Chicago is not a catastrophe, nor is it a disaster, not on the usual scale of things, anyway. It is a disruption that can have unfortunate consequence in the individual case, but generally people deal with it and often are better for it. Even so, the imagery is part of a larger archive of public art, and the artistic insinuations may be worth considering. It’s not often that we take the time to consider just how the present may already contain the seeds of futures we’d rather not see.

The point, howover, is not to become either morose or dismissive. The lesson once again lies in the last photo: The future might not be worse or better than the present, but simply different. That might be the most disturbing thought of all.

First photograph by Henry C. Webster, Chicago. Additional photographs by E. Jason Wambsgans (2 & 3) and Brian Cassella (4 &5) for the Chicago Tribune.

4 Comments