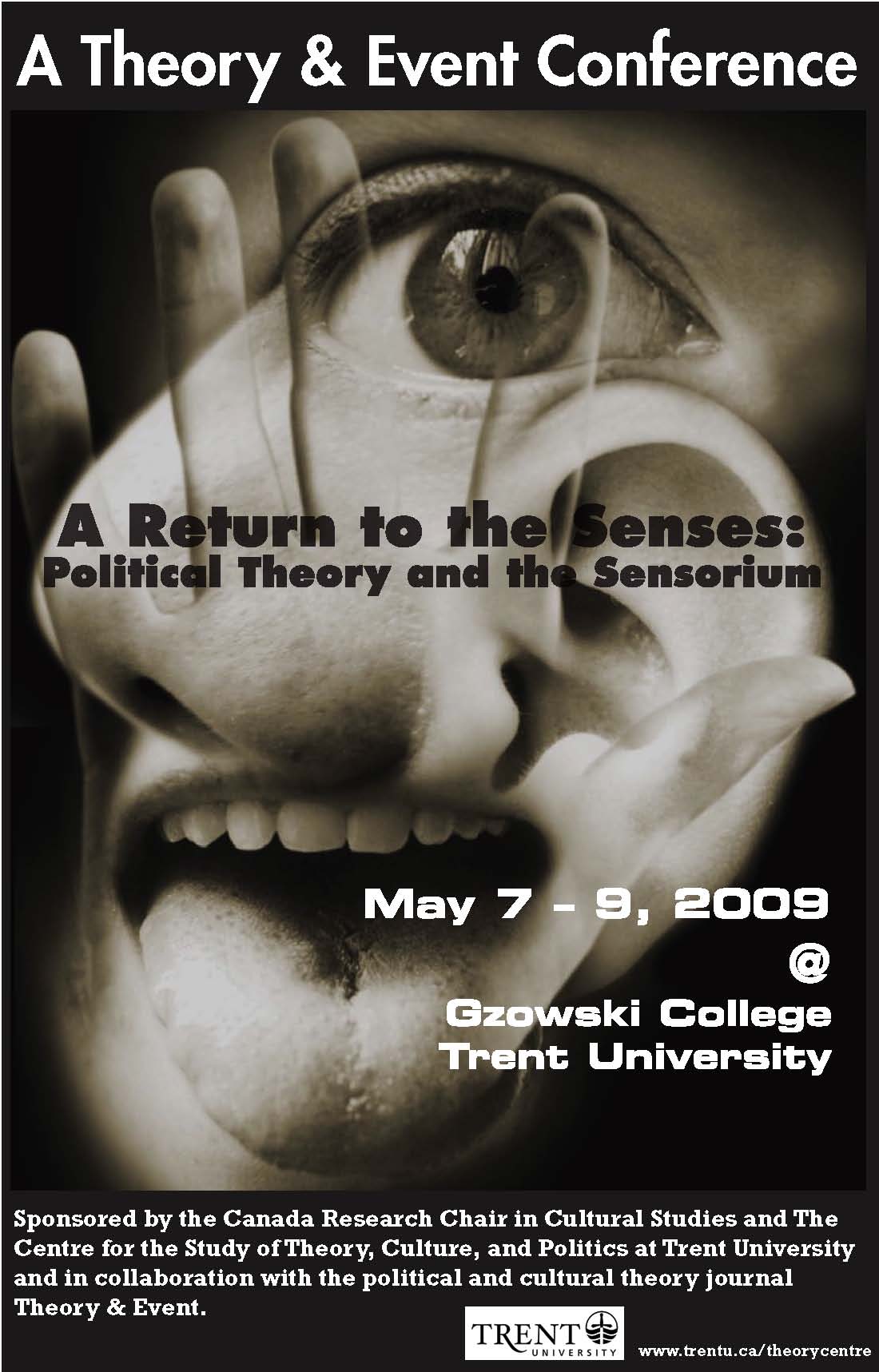

It’s a beautiful desert image, something one might see in Arizona Highways or National Geographic. And the dark brown ridge snaking towards the horizon? It could almost be a natural formation, one exemplifying the waveform topography and severe plain surfaces of this barren environment. Close inspection reveals construction material, however, and so it could be an art installation: perhaps something by Christo that will be up for only a short time before being dismantled to return the scene to pure space and light.

Don’t be fooled by the beautiful design. You are looking at a section of the “fence”–otherwise known as a wall–that separates the US from Mexico. This massive construction project has been going on for several years now, almost completely under the radar. You will not have noticed a shortage of illegal alien labor in your city, but you can rest assured that they had to become ever more ingenious or courageous to get here.

I wish we had built the wall as an artistic work–if only to take this one photograph before tearing it down. Others will say the wall is justified, of course, even though the US once boasted that it had undefended borders. Whatever the cost-benefit ratios for various immigration restriction technologies, there is additional significance any time a nation creates a wall.

Walls are uniquely symbolic, and paradoxically so. Those erecting them are demonstrating their power, wealth, and commitment to control and order on their terms. Think of the great powers who have built walls: China, Rome, the Soviet Union, Israel, and now the US.

The same list reveals the other side of the symbol: a wall is an admission of political failure. Walls are put up precisely because the state cannot keep people out–or, with the Berlin Wall, in. They are erected because a people can’t be beaten, dominated, bought off, or otherwise managed without changing the state’s relationship with the world.

We might want to think of the wall along the border of the US later in the year. In November, 2009, there will be official and unofficial celebrations of the 20th anniversary of the collapse of the Berlin Wall. The media will be circulating photographs such as this one.

Such photographs should be valued. They remind us that a wall once was torn down by the power of the people. The nation is still present in this photo, signified to any German by the Brandenburg Gate in the background, but the people are in the foreground and have become the living enactment of the dissent and democratic self-assertion previously known only through the graffiti smeared across the brick barrier.

The people of Berlin could take down that wall because they were on the right side of historical change, and because it had become all too clear within East Germany that a society cannot thrive by walling itself in. In the 21st century, the US government is on the side of the builders of walls, which I’d like to think is not the right side of historical change. The first photograph above is part of the process of creating an enclaved nation: you see only an empty space and bare surfaces–no people, no dissent, nothing political at all, really, just a natural formation. The border is both secure and desolate, nothing ordinary citizens need think about. All that remains is to await the barbarians.

Photographs by David McNew/Getty Images and from the Wikipedia Commons. For another comparison of the two walls, go to the announcement for the 2009 Joint Conference on “Migration, Border, and Nation-State.”