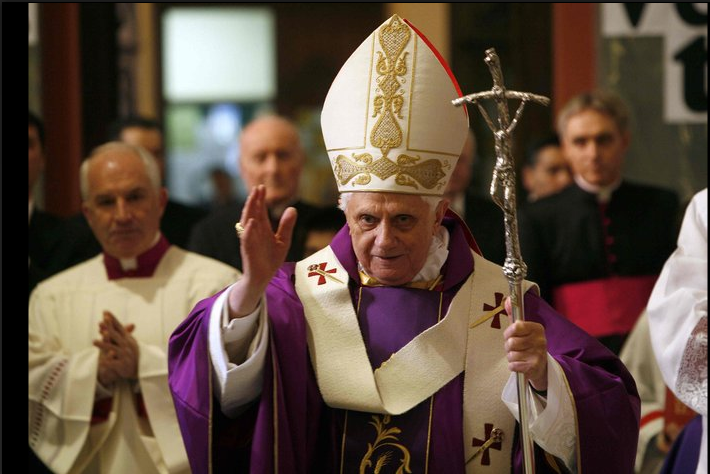

Some get light-headed at the sight of blood, others get nauseous, kids are amazed, nurses get used to it. Most of the time, we don’t see it. Despite the gallons of fake blood spilled in the movies, the sight of the real thing continues to be a shock. That will be one reason you don’t see it often in a family newspaper. The daily slide shows have more leeway, however. That’s where I found this image:

The caption stated that a number of people had been injured when a rally in Katmandu was broken up by police wielding tear gas and batons. (Why do they call them police?) Now this photo isn’t grotesque. Indeed, it’s not too far aesthetically from the more familiar tourism photos of Buddhist monks in colorful robes, or from other images that have been in the news lately from the many carnivals and similar rites of spring that are going on around the globe. And one could suggest that it’s somewhat staged: he could be propped up for the camera, and the red, white, and blue sign in English certainly is directed at the Western media. Besides, blood flows freely above the lip line; he could just be nicked as if by shaving, right?

Wrong. He’s been clubbed, and he’s being held up because he might collapse. He is not colorful. He is bearing witness to violence. If they will club him in the public square, you can imagine what can happen behind closed doors. But we don’t go there, and that is why it is important to see the blood. Stunned into silence, his body now speaks for him.

If we were to measure speech, perhaps it could be done in blood. How much has to be spilled to secure the right to speak freely? How much has to be said to stop the flow of blood in police states and failed states and war zones and ghettos around the globe? How often will we turn away rather than look, nauseous, at the blood streaming from the victims of beatings and bombings and drive-by shootings? When will we face this:

Sadr City, Baghdad, a local clinic after a firefight between US troops and militiamen. It makes me sick.

Photographs by Brian Sokol/New York Times and Ahmed Al-Rubaye/AFP-Getty Images.