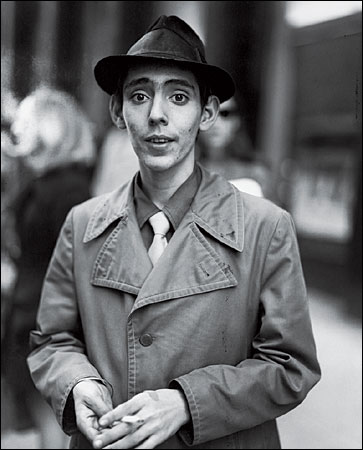

The photograph below doesn’t capture the full effect the image had when smeared across one page and part of another in a print edition of Sunday New York Times Magazine (12/23/07).

I’ll bet you get the idea even without the grainy feel of the overblown printed image. The photograph is by Delphine Kreuter, entitled “Le rouge a levres,” and part of the exhibition “J’embrasse pas” at collection Lambert in Avignon, France. The image was used to decorate a puff piece on the current fashion for red lipstick.

I’ve posted before about how fashion carries the enormous energies released by our being social animals. This image is a show stopper on its own, however. The human face is reduced to flesh and teeth. Those teeth are fashion model perfect but also vulnerable, isolated in the center foreground as if being targeted. The flesh is distended, distorted, manipulated; but for the social context of applying make-up, the angle of the head and its pallor would suggest something closer to a body undergoing surgery or being laid out for an autopsy. It’s easy to think that the hands don’t belong to the face which is being abused somehow, held down, twisted, smeared, exposed, marked.

And marked with red. The Magazine article mentions the usual sexual symbolism, but the image goes beyond that. Like fashion itself, the color exposes what it covers. In this image, we see the thick yet pliable tissues of the mouth, its minute seams and folds, its physical weakness. This mouth is not the typically invisible organ of human communication, but instead an orifice–like the others, a place where the body is folding in on itself but not quite sealed. It does not speak, but rather is a place for decoration, a thing that can bear a sign. The smear of red doesn’t quite cover the form of the lip, and so artistry itself is exposed, and with that the truth that style is imperfect, temporary, and completely artificial.

Artificial, but to die for. The image catches its subject and its audience so powerfully because we also know that what appears to be violent is also voluntary. The person photographed might have been male, but the image captures how women often are subjected to physical distortion and discomfort in the name of fashion. More to the point, fashion and violence spring from a common source.

This tension between the brutal animality underlying social life and its superficial articulation as mere fashion permeates the Magazine’s presentation of the story. It is there in the contrast between the text and image, and between title (“The Human Stain”) and subtitle (“Red lipstick continues to leave its indelible mark”) and within the story itself, which blends fashion twaddle (“red lipstick is having a moment”) with reports of vandalism and of artists who use it as “a tool of symbolic defacement.” One is quoted: “‘Red is primal and violent . . . It’s the universal gash.'”Against such celebrations of violence, the mere fashion statement might be a social achievement.