Saturday’s New York Times included these stories: First, the confirmation of Michael B. Mukasey for attorney general had hit a “rough patch” because Democrats were suggesting that they might oppose confirmation if the nominee “did not make clear that he opposed waterboarding and other harsh interrogation techniques that have been used against terrorism suspects.” Second, a review of the movie “Saw IV” advised viewers to “Imagine every conceivable form of torture, then add the inconceivable.” Third, a report on the photographs, and photographer, used by the Khmer Rouge to document the arrival of those who had been brought to the Toul Sleng prison to be tortured and killed. You might see a pattern. . . .

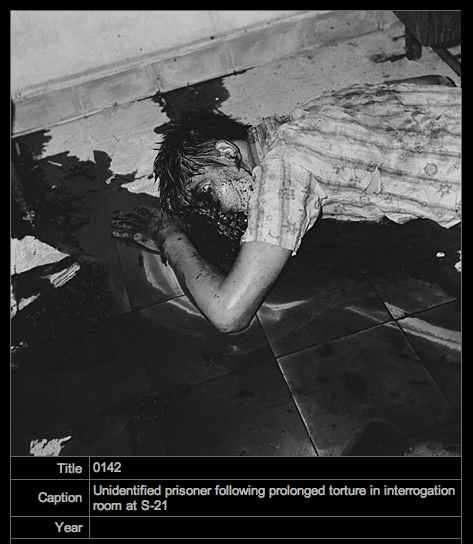

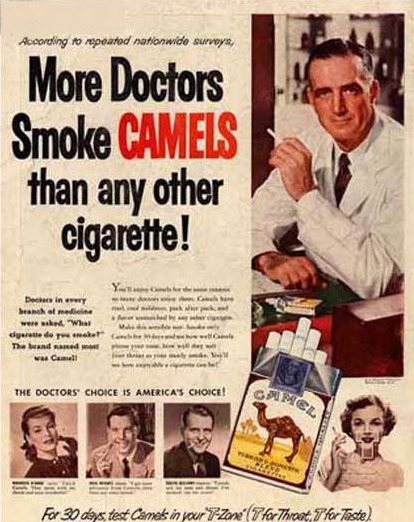

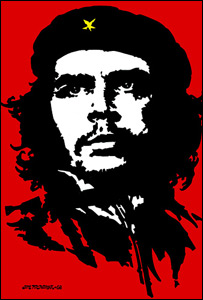

Do you also see a sliding scale? Say, from the torture we do, which the administration would like to think is a matter of semantics, to the torture we imagine for cheap thrills, which receives the stern rebuke of an R rating while remaining business as usual at the cineplex, to the torture done by others, which is the subject of documentary reportage. Even so, the Times story on the prison photographs is a service. The problem they, and we, face is how to confront torture without inadvertently contributing to its normalization. News media should be faulted at times for not showing the harm done by those acting in our name, but we don’t want the news to become “Saw XXX” in real time. It should be said, however, that surely it becomes too easy to minimize torture when both Gonzales and Mukasey have said they oppose torture while condoning its practice, and when audiences watch torture scenes on film and TV that they know involve no real pain. That is why we need to see this:

This is one of the images at the Tuol Sleng Museum website. It should be said that the Times did not include this photo in its story. Perhaps they should be faulted for that. I don’t think so, because what they did show was even more horrific:

She is another “unidentified prisoner.” She also is a young girl who subsequently will have been tortured and killed. I can’t imagine. . . . And if anyone says that at least the US government doesn’t torture little girls, we already have slipped too far into the abyss.

Photographs from the Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide, http://www.tuolsleng.com/.