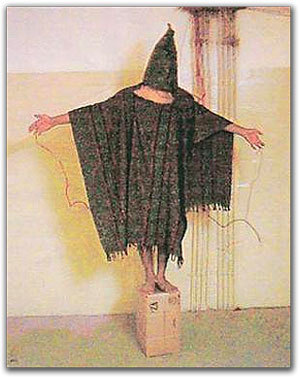

This image from the Washington Post Day in Photos lies right across the line between soft news and hard news.

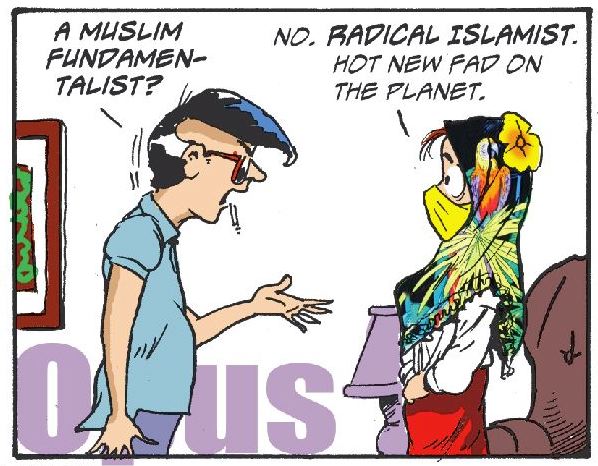

On the one hand, it’s a visual joke. The incongruity of a woman from a traditional society carrying a TV rather than water or the wash on her head at once upends and reconfirms Western assumptions about the Arab world. She’s not completely not modern, and modern civilization is what she desires. See: the woman values that TV so much that she will carry it instead of more traditional necessities. Imagine: she’s all wrapped up and yet gets to see the world through the wonder of modern technology. On the other hand, the woman is engaged in the difficult task of carrying her household possessions through a war zone while probably leaving much behind. The caption adds that “about 2,000 Iraqis leave their homes every day due to violence and economic uncertainty resulting from the four-year conflict.”

Although cast as a representative of displaced Iraqis, I doubt the woman will elicit much sympathy. Indeed, the image calls the bluff of the serious captioning: the photo is striking but not for the reason given. As noted several times before in this blog, the burqa troubles the Western gaze whenever it is is placed in modern context. (Within the traditional setting, it confirms ideological assumptions instead of challenging modern norms of transparency.) By walking with the TV balanced on her head, the burqa-clad woman becomes a cyborg, both human and machine, organic and artificial, traditional and modern. She now has two heads, one veiled, turbaned, and a platform for the other, which is a blank screen capable of channeling the vast information flows of the modern media. Despite the visual joke, the latent fascination of the image is that she has become monstrous. Not terrifying, but more akin to a freak show. The fact that the photo is half soft news and half hard news reinforces this sense of an unnatural though not too dangerous mixture.

Of course, it’s not news at all. We know all about Al-Jazeera, and scholars, not least Martin Marty’s Fundamentalism Project, have documented that fundamentalists of all religions have no problem rejecting modernity’s values while becoming cutting-edge producers and avid consumers of modern media. It turns out that modern liberals are the ones who have a hard time managing that contradiction. Which is why the photograph above, which could be seen in a very ordinary way, instead implies that the two civilizations can never be blended but must instead be joined only precariously, amidst violence.

Photograph by Alaa al-Marjani/Associated Press.