Visual Communication Quarterly

Call for Papers

Visual Portfolio: Domestic Images in the Digital, Online, and Viral Era

Guest Editors: David D. Perlmutter and Lisa Silvestri, The University of Iowa

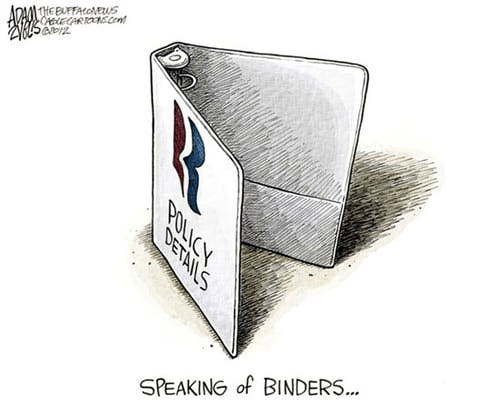

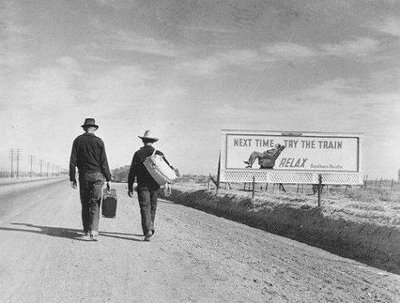

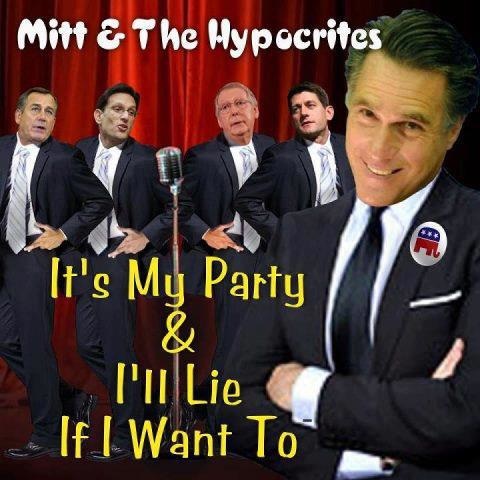

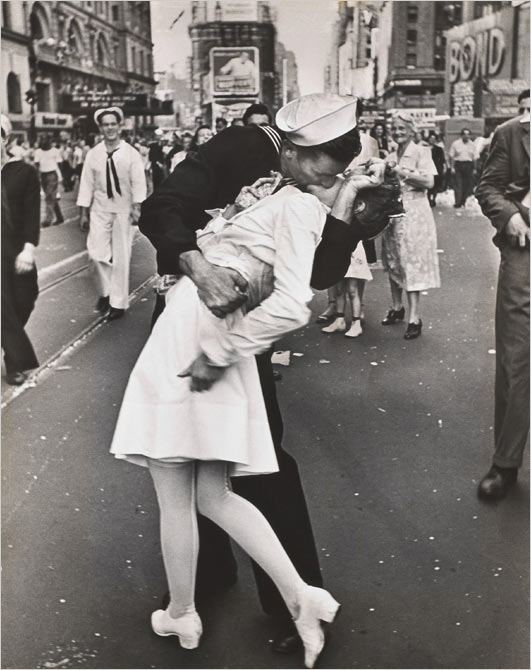

Today anyone with a cellphone and an Internet connection can create and distribute images without professional training or a governmental or industrial institutional affiliation. Whether funny cat YouTube uploads, vacation videos (from a tsunami site) or pictures of the humiliation of Iraqi prisoners, images that once fell under the genre of “domestic” are now regularly erupting onto world attention, controversy, and influence. Likewise, ordinary citizens are delivering the first visual “draft of history” because they are first on the scene of breaking news-from terror-filled moments in a London subway after a bombing to an airliner landing on the Hudson River.

This special issue of VCQ seeks scholars and practitioners who study or document the blurring between “home” photography and “public,” professional, or commercial photography as it becomes increasingly indistinct in our viral digital/online/social media age.

Among possible questions to ask: What does it mean when the “home mode” goes viral? How does the role of the professional photographer and industry change when “citizen journalists” are creating so much public content? What new genres of photography are emerging in the home-public fusion? How does the domestic origin of an image affect its reception? What are the historical antecedents to this phenomenon (e.g., images of the Holocaust that were originally souvenir snapshots by its perpetrators or domestic scenes of celebrities made famous after their deaths?)

VCQ: Visual Communication Quarterly solicits contributions for an upcoming special issue on the domestic image. VCQ welcomes essays that consider the relationship between “home” and “public” modes of photography, visuality in a viral era, digitization, Photoshopping, cropping, and dissemination. In addition to theoretically grounded, critical essays, we will consider the submission of visual essays and photo pieces. Max. word length for essays: 7500.

Deadline for submissions: February 20, 2013

VCQ: Visual Communication Quarterly publishes scholarship and professional imagery that promotes an inclusive, broad discussion of all things visual, while also encouraging synthesis and theory building across our fascinating field of study. See: http://vcquarterly.org/ for submission style and guidelines. Please email an electronic version of your essay (as an MS Word document), along with a 100 word abstract, to david-perlmutter@uiowa.edu. For portfolios, send inquiry first.

EDITOR

Berkley Hudson, Missouri School of Journalism