It has been a full year since Japan was overwhelmed by an earthquake and tsunami and like clockwork the major media slideshows have responded with a series of “then” and “now” photographs (e.g., here, here, and here) marking the slow but steady progress of an advanced society—in many regards a society much like our own—as it returns from utter devastation to a bustling, self-sustaining economy. It has not fully returned, but it is on the path to recovery and the comparisons surely invite our sympathy and admiration. In January we saw a similar set of visual comparisons (e.g., here) on the one year anniversary of the earthquake in Haiti, but with this difference: while it appears that Haiti has recovered some from the disaster, it continues to be an impovrished, utterly dependent, “other world” nation that invites neither our identification nor our sympathy so much as our pity.

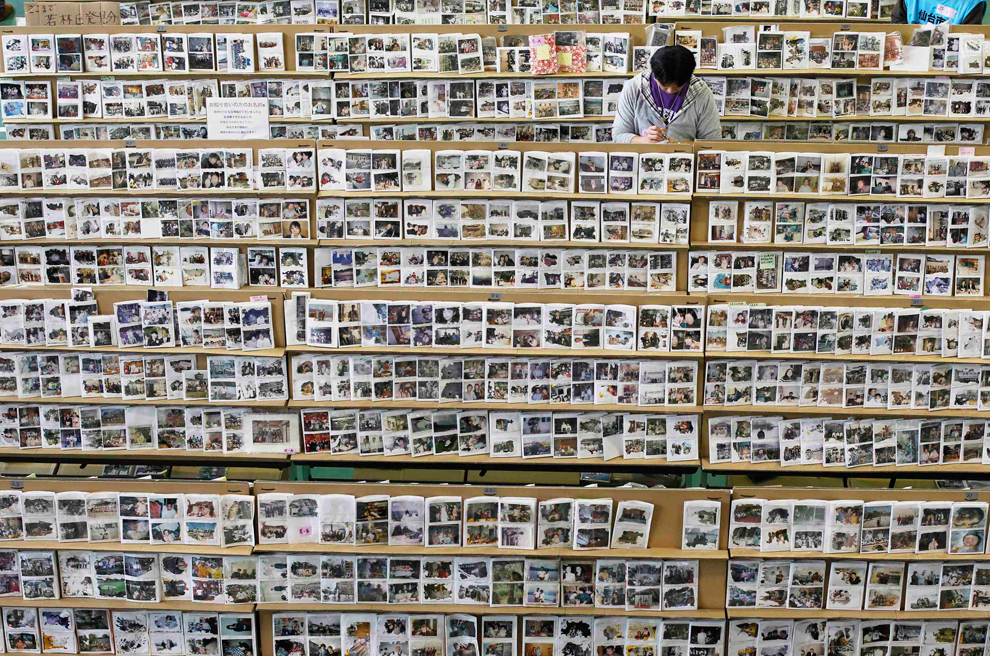

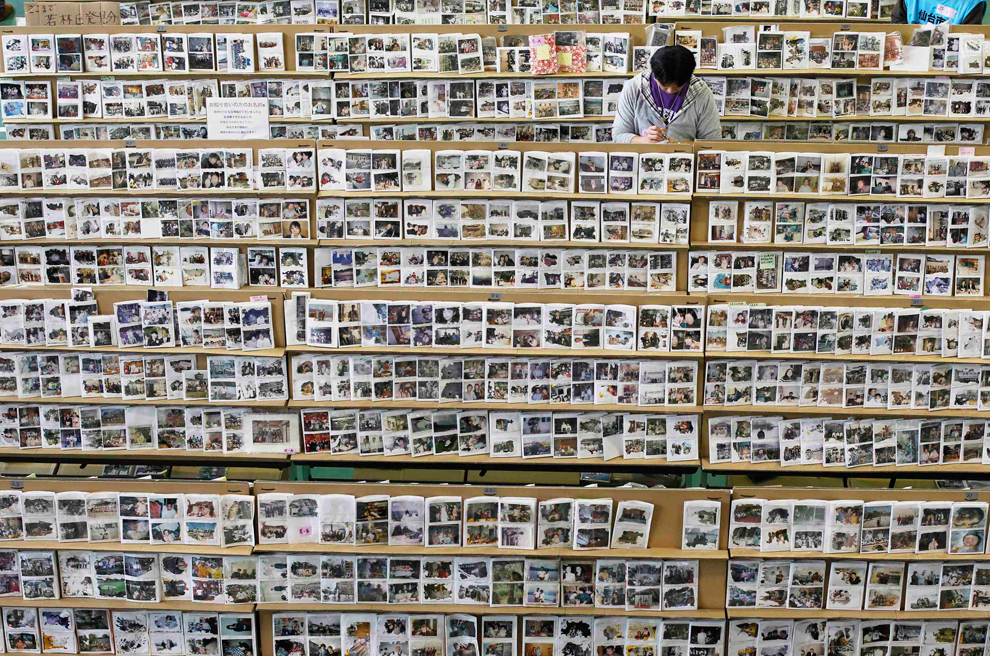

The differences between Japan and Haiti are signified in a multiplicity of ways, not least in how the devastation in Japan seems to have been largely structural, effecting roads, bridges, buildings, and other forms of physical property, whereas the devastation in Haiti has been more social and economic, exacerbating an already starving, unemployed, uneducated, and generally impecunious population. The above photograph is telling in this regard. It is a photograph of lost photographs collected in a local school gymnasium in Natori, Japan, waiting for their owners to seek them out and recover them. Some are quite obviously old, perhaps even antique, and thus mark a sense of historical continuity that spans generations and thus mitigates the impact of the more recent and comparatively minor “then”/”now” dialectic that commemorates no more than a span of twelve months. But perhaps more importantly, these photographs are obviously cherished items, their value signified not just by the fact that they are framed and were thus objects of display in the home, but because they were patiently and laboriously culled from the detritus left behind by the earthquake and tsunami and collected with the hope that they would be found by their respective owners.

Collection centers such as the one above can be found throughout Japan, and some are down right enormous as in the photograph below which identifies a site that contains more than 250,000 photographs . And the point should be clear: more than lost property, these lost photographs are quite clearly significant momento mori, cultural artifacts that identify the society that takes them and preserves them as a modern, technologically sophisticated, bourgeois civilization (not that one has to be bourgeois to take and keep photographs, and the practice of snapshot photography cuts across all economic classes where it is an established cultural convention, but it rarely occurs in societies that lack an established middle-class).

And so it is that when we turn to retrospectives of Haiti we don’t find the preservation of family photographs at all. That is not to say that photographs are unimportant, but as with the image below, they signify not an established, modern cultural practice, but rather a modernist intervention of sorts.

Here a Haitian woman shows a photograph of herself as she was pulled from the rubble of a house that had fallen upon her. The photograph was taken by an AP photographer and then given to her. It is clear that she values it, but importantly it is more a curiosity—or perhaps a marker of humanitarian aid—than a conventional cultural artifact, and as such it designates the society in which she lives as pre-technological if not in fact premodern. One finds a similar curiosity and intrigue displayed and accented in photographs that show Haitian children (here and here) being introduced to cameras and photography by the Art in All of Us project.

The simple point would be to notice how two societies are distinguished by their attitudes towards photographic technology: one modern and mature, the other premodern and either immature or innocent, but in any case defined as childlike and needy. But perhaps more important is the way in which the photographs above function in each instance as media that model social relations, inviting us to see and be seen as members of a social order driven by the differences that simultaneously separate us and connect us. That, perhaps more than anything, defines the modern condition.

Photo Credits: Daniel Berehulak/Getty Images; Toru Hanai/Reuters; Dieu Nalio Chery/AP Photo

1 Comment