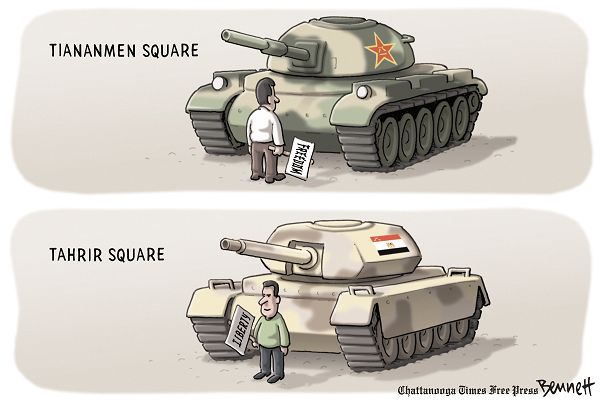

I’ve spent the last several days looks at hundreds, maybe thousands, of photographs of the political unrest in Egypt. At first blush there didn’t seem to be anything that distinguished the photographic record from the images representing political strife in other Middle Eastern countries in recent times – Lebanon, Iran, Pakistan, Greece, Tunisia, etc.: burned out buildings and cars aflame, streets littered with rubble and trash, images desecrated or burned in effigy, hands and fists raised in rage and protest, the spray of water cannon and the haze of tear gas, jack booted police wielding automatic weapons and bullet proof masks and shields standing off against sandal and sneaker clad protestors armed with sticks and stones, injured or dead bodies, makeshift funerals, and tanks … lots and lots of tanks. On careful examination it was the photographs of tanks, such as the one above, that really set this collage of chaos and violence apart.

The tank, of course, is a visual trope for oppressive regimes, whether employed by autocratic rulers or occupying forces. Think of the Nazi Blitzkrieg or the Prague Spring or Tiananmen Square or the ground assault in Operation Desert Storm, or more recently the deployment of Israeli tanks in Gaza. Wherever we find it, the tank is visualized as a faceless, inhuman, mechanized marker of military might. While not truly invincible, its sheer size and robotic appearance nevertheless casts it as simultaneously magnificent and terrifying, an intimidating—perhaps even sublime—symbol of power and force. An instrument of technological rationality, it leaves no space for reason. Indeed, its very presence implies a “take no prisoners” sensibility, and where tanks appear there is normally no occasion for dialogue.

But in Egypt in recent days something strange has happened, as the military tank has taken on something of a human(e) face. In the photograph above the driver of the tank is actually engaged in a discourse of some sort with the protestors. According to the caption the protestors are imploring the tank driver to join their opposition to the Mubarak government. There is no way to know if that is what is actually taking place here, but in a sense it really doesn’t matter, for the very fact that talk has mitigated (if not actually replaced) physical violence suggests the possibility of a less than tragic outcome.

Of course, one tank driver talking to a group of protestors can hardly be taken as the liberalizing of an autocratic regime. But the fact is that there are numerous such photographs circulating throughout the various news outlets that indicate the presence of the Egyptian military as something of a stabilizing force, managing the tension between the protestors and the police (apparently the active and oppressive security arm of the Mubarak regime) especially in and around Cairo’s Tahir (Liberation) Square. So, for example, there are numerous images of protestors taking time out to pray en mass as members of the military standing on tanks look on—and in one sense, at least, appear to be “looking over” the protesters.

Perhaps the most poignant of such tank photographs is the one below:

It is hard to know exactly what is going on here. It would seem that the protestor is handing the baby to the soldier on the tank. But why? There is no way of telling for sure, but perhaps that is the point. The offer of the child is not driven by an obvious or inexorable instrumental rationality, but rather is something of a more open, reasoned symbol of unity or solidarity between the people/protestors and those charged with securing their “freedom”—whatever that term might mean in the Egyptian context. And in the process, the negative symbolic resonance of the tank is neutralized or domesticated —notice the smiles on everyone’s faces— as both those above and those below are connected by touching their common future. In this context, the tank, and by extension the military itself, becomes a productive buffer between the people and the government as events work themselves out. To get a sense of why this might be important, consider the alternatives if the military were to side with either the Mubarak government against the protestors or visa versa.

Of course we should never forget that tanks are weapons of war. And more, that they are commonly used as instruments of oppression and control, both rhetorically and otherwise. But at least in this one instance they seem to have been deployed—or at least recast—as symbols of a more reasonable public culture in which the tension between opposing forces is held in stasis.

Credit: Mohammed Abed/AFP/Getty Images; Asmaa Waguih/Reuters.

Cross-posted at the Shpilman Institute for Photography blog.

4 Comments