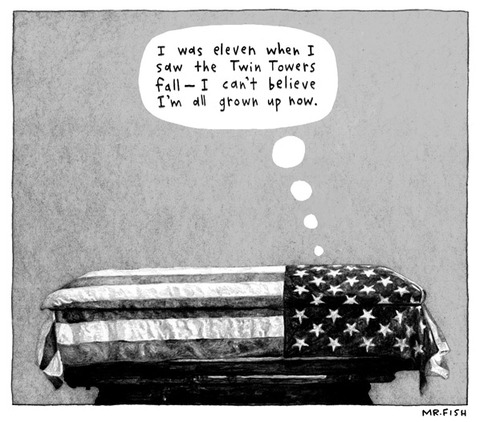

My first impulse on seeing various iterations of this photograph—this is the official White House version—was to take a pass on commenting on it. After all, I surmised, it is such an obviously orchestrated photo-op that there is very little that needs saying—a point seemingly underscored by the fact that many of the numerous newspapers that showcased the photograph on their front page chose not to include any front page commentary beyond a simple caption (including the New York Times). And perhaps this was with good cause as most articles written about the event emphasized such key facts as the clothes being worn, the type of glassware being used, and the variety of beer being consumed (it turns out that the president is a “Bud Lite” man). But then I watched the Colbert Report and was reminded that the point of this meeting had something to do with what President Obama had called “a teachable moment.” And the more I looked at the photograph the more I wondered, what exactly is being taught?

The photograph shows four men sitting at a round table having a beer and engaging in private conversation. We know it is a private conversation in part because the four men have their attention directed towards one another and seem oblivious of the fact that they are being observed by a row of photographers some fifty feet away. But note too, that the very setting underscores the sense of privacy as the table is conspicuously set apart from the rest of the yard in what middle class homeowners might recognize as a patio carefully shielded from public view by trees and planters. The sense that this is a private meeting is further accented by the photograph as it is shot from afar with what appears to be a standard 50 mm lens that locates the viewer in public space at some distance from the event, and most importantly, clearly outside of hearing range. Indeed, there is a quality to the photograph that suggests that the viewer is something of a voyeur, intruding where they don’t belong.

Put simply, everything about this photograph signals that the event is a private moment, albeit one that was carefully orchestrated as a spectacle for the passive consumption of the national public. And, indeed, when someone in the media dubbed the meeting a “beer summit” the president was very quick to point out that this was not an official or even political event. Rather, he emphasized, “This is three folks (sic) having a drink at the end of the day and hopefully giving people an opportunity to listen to one another.” The point to note here, of course, is who got “to listen” — and who was consigned to view the event from a distance and without sound.

The lesson to be learned then, it would seem, is that racial tensions of the sort that animated this meeting are best handled as private matters, issues to be resolved by adults (not citizens) between and amongst themselves and outside of the public eye. And if the outcome is little more than to “agree to disagree,” well, what’s wrong with that? Perhaps this is what it means to live in a so-called “post-racial society.” The difficulty is that such an approach grossly simplifies the nature of the problem of race in contemporary society, and especially in instances where racial matters are implicated by the use of state violence to manage the citizenry. Following the meeting Professor Gates was quoted as saying, “When he’s not arresting you Sgt. Crowley is a really likable guy.” I assume that the comment was made with tongue planted very deeply in cheek, but in any case the irony is profound and very much to the point, for what is at issue is precisely how Sgt. Crowley behaves when he is enacting his role as an officer of the state, wielding badge and gun. And whether he was right or wrong in arresting Professor Gates, surely that should never be a private matter shielded from the public view.

Photo Credit: Lawrence Jackson/Official White House Photo