“It’s summertime,” and as the saying goes, the “livin’ is easy.” Or at least it will be for your NCN guys as we take the week off to recharge our batteries before the political conventions kick in and the new school year begins for us. It has been a great year for us and we appreciate the support of everyone who has written in with comments and suggestions, criticism and encouragement. We will be back on August 18th.

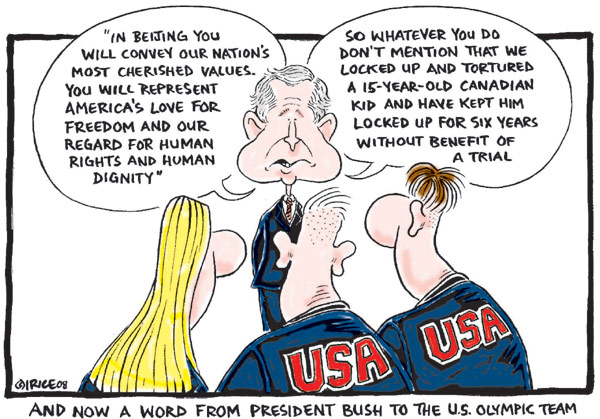

Sight Gag: In Search of Human Rights (and Wrongs)

Credit: Cameron Cardow; Ingrid Rice

Our primary goal with this blog is to talk about the ways in which photojournalism contributes to a vital democratic public culture. Much of the time that means we are focusing on what purport to be more or less serious matters. But as Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert often remind us, democracy needs irony, parody, and pure silliness as much as it needs serious contemplation. For our part, we will dedicate our Sunday posts to putting such moments on display in what we call “sight gags,” democracy’s nod to the ironic and/or the carnivalesque. Sometimes we will post pictures we’ve taken, or that have been contributed by others, or that we just happen to stumble across as we navigate our very visual public culture. Sometimes the images will be pure silliness, but sometimes they will point to ironies, poignant and otherwise. And we won’t just be limited to photography, as a robust democratic visual culture consists of much more. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.

Color and Politics

This week we are pleased to welcome Aric Mayer as a guest correspondent. Aric’s work has previously been featured in our Photographer’s Showcase here and here.

The entire media experience this week seemed dominated by questions of color and politics. Numerous polls were taken asking variations of the question, “Is America ready for a black president?” The results came back mixed. Maybe yes, maybe no. The question here has to be, what exactly does this mean?

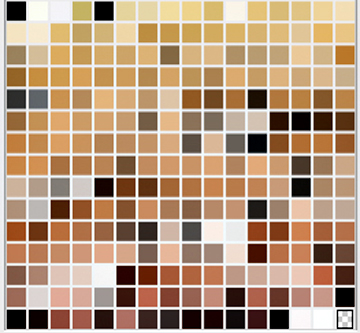

The color palette below was generated from four popular images of Barack Obama and John McCain. These are the combined colors needed to recreate images of both of their faces in their entirety.

As a photographer with extensive experience in photo retouching for national publications, one of the first things that I learned was how to measure the color of a skin tone in an image. Colorimetrics is an interesting and exact science, and suffice it to say that it is possible using ink densities and light measuring tools to describe skin tones in very specific ways. What is surprising is how subtle the differences are between the skin tones of all races. Hues across the spectrum of ethnic groups vary only by a few percentage points. It turns out that all the possible hues and tones of human skin color do not make up an actual rainbow of diversity, but in fact are only a tiny sliver of the possible colors in the visible spectrum. Indeed, skin tones exist in a fairly mundane part of the spectrum, consisting mostly of light tans into dark browns, with subtle variations in color. These colors are dwarfed by the incredible diversity of other colors in the world, greens for instance, the color of chlorophyll. While we are hyper-attenuated to the cultural meanings of skin colors, we tend to categorize them into large groups; what we lack is a cultural language with which to accurately describe their appearance.

Biases and barriers in the political polls are written right into the questions. Barack Obama is not visibly black, nor is John McCain actually tinted white. But the cultural divide between them is frequently shown to be as extreme as the end points on the possible spectrum. The real polling question should not be, “Is America ready for a black president?” But instead, “Is America ready for what might lie between the two extremes?”

The More Things Change …

What you are looking are members of the Russian Olympic Woman’s basketball team just prior to an exhibition match against the United States in Hainilng, China. The young women in the front with her hand on her chest and her eyes fixed above is Becky Hammon, a former All American at Colorado State University and currently a member of the top-ranked San Antonio Silver Stars of the WNBA. She is also a native of South Dakota and, as of this past year, a naturalized citizen of Russia. There has been something of a small controversy brewing here, as some such as U.S. basketball coach Anne Donovan, have accused her of being unpatriotic, but Hammon’s more numerous defenders have been quick to point out that there is nothing new about naturalized citizens playing in the Olympics, and the simple fact is that she was not originally invited to try out for Team USA and this was her one opportunity to participate in the Olympics. And truth to tell, the look on her face as the Star Spangled Banner plays tells you what uniform she would much rather be wearing, and given the intensity of the gaze—in contrast to the bored and nonchalant indifference of her teammates—I doubt it is simply because it would give her a much better chance of winning a gold medal. This is not a picture of an unpatriotic U.S. citizen regardless of the uniform she is wearing. Indeed, it displays the passionate love of country with a powerful and subtle nuance that reminds us of the tension between nationalism and individualism.

There is more to this picture, however, than the pained and conflicted loyalties of a single, individual athlete, however pronounced that might be. For it also stands as a marker of the changes that have taken place in world of geopolitics over the past 30 years. In the late 1970s the Cold War between the United States and Russia (then the USSR) was at full tilt and the tensions animated by ideological differences between western capitalism and Soviet style communism were no more evident than in the politics of the 1980 Winter and Summer Olympic games held respectively in Lake Placid, NY and Moscow, Russia.

The Winter Games came first, and the picture above stands in stark contrast to the most famous image to come from the Lake Placid games of a ragtag collection of U.S. college hockey players who “miraculously” defeated a Soviet team which, by almost any standard, consisted of seasoned and “professional” veterans.

The present day image comes from before the sporting event not after, and so it is marked by a degree of calm and reserve that we would not expect to find following an upset victory, but the larger point to be made is that the contemporary photograph would never have been taken in 1980 (and if taken surely not featured in the NYT), precisely because it would have been anathema to the spirit of the times—a Cold War world where national citizenship trumped all. We have no doubt not yet moved fully into the “globalized” world that recognizes the legitimacy of post-national citizenship—and, indeed, we clearly continue to live in a country where at least one version of the cold war optic organized around the notion that walls of national separation and isolation might be a good thing persists— but that such a picture as the one of Hammon could even be taken and featured in a mainstream news outlet suggests at least the possibility of such transformation to a more complex and nuanced sense of citizenship on the worldwide stage.

But there is perhaps one additional point to be made as well. For while we have a photograph from Lake Placid that helps to foreground the difference between a Cold War world and a post-Cold War world, there is no contrasting image to be found from the subsequent Summer games later that year in Moscow. The reason, of course, is because the U.S. led a boycott of the Moscow games and no such pictures exist period. And the reason for that boycott: in the summer of 1979 the Soviet Union had invaded …. Afghanistan. There are differences, to be sure, as we are tracking “terrorists” and not seeking to oppress “freedom fighters,” and yet, the more things change …

Photo Credit: Elizabeth Dalziel/AP

Looking From the Inside Out

What we have here is a photograph shot from inside the new, “bullet train” that will begin running on the high speed Beijing-Tianjin express railway starting on August 1, 2008, just in time to accommodate the high traffic of foreigners who will be attending the 2008 Summer Olympics. It runs at a speed record 394.3 kmh, thus traversing the 135 km from Beijing to the port city of Tianjin in less than 30 minutes and representing the height of modern urban mass transportation technology. The photograph puts the viewer just behind the driver, and thus aligned with both the technology and, perhaps not so incidentally, efficient and effective modern state control of the world in front of it.

What struck me most about the image is how it operates both in tandem and in tension with the now famous photograph of the lone protestor stopping the tank near Tiananmen Square in 1989. On the one hand, it shares all of the aesthetic conventions of high modernism that we find in the iconic image of the man and the tank. The orientation is universal rather than parochial, geometric rather than organic, functional rather than customary, and so on. This aesthetic—what anthropologist James C. Scott calls “seeing like a state”— is reinforced by the tonality of the image which, while in color, nevertheless veers towards the grey scale of the photographic spectrum and thus gestures towards the abstract and schematic orientation of much scientific representation.

On the other hand, there is something of a reversal of perspective. In the original Tiananmen Square photograph the viewer is an outsider looking in on another culture from a safe distance—and in this context it is important to note that as famous as the 1989 photograph is in the western world for its manifestation of an heroic, liberal individualism, it has very little recognition and resonance within China itself—whereas here the outside viewer is invited to share the panoptic vision of the modern state from the inside. And note how that view is circumscribed by the window that narrowly restricts any peripheral vision, creating something of a tunnel vision effect that enables us to see no more than how clean the tracks ahead are, how totally devoid they are of anything that might derail the train from its appointed task of moving passengers from here to there quickly and efficiently. In short, we can only see what the apparatus—state, technological, what have you— enables us to see. And, of course, this can be a problem when you are on the inside looking out, whether as the driver or as an unwitting passenger.

The question then is, what are we missing in the process? If there were a lone individual standing on the tracks trying to stop the train he or she couldn’t be seen—and at this speed perhaps all that would remain is that reddish-brown smudge on the windshield. Then again, protestors—individuals or otherwise—are not likely to stand in the way of this train as they have been relegated to “Olympic Protest Zones” in designated parks, and at that it is unlikely that most dissidents will successfully negotiate the bureaucratic barriers to political protest that include applying for a permit in person, five days in advance of a demonstration, and with detailed information such as the slogans to be used, the number of demonstrators, and so on. Maybe that is what we miss when we look only from the inside out.

Photo Credit: STRA/AFP Getty Images and The Big Picture

Perpetual Childhood in America

Social documentary photography can occur almost by accident, especially when the subject is the middle class. This photograph from the Sunday New York Times is a case in point:

The caption reads, “Just before the official start of visiting day, parents try to get their daughters’ attention as they stand on the side, surrounded by numerous gifts that await the campers.” I like the way the photographer captures the parents as they might appear to children. (Animals at the zoo might have a similar experience.) The spectators are put on display, and despite their size they remain distant while signaling more than can be taken in. The dads appear either stern or clueless while the moms seem to be over-the-top emotional. In either case they are likely to be a load, so the gifts had better be good.

It might be more revealing yet to look at the parents from the perspective of an adult. From that perspective, doesn’t it seem that most of them look like children? Except for the grouchy old guy in the middle–we’ll get back to him later–these adults are dressed like kids. The t-shirts, shorts, tennis shoes, capri jeans, are not only casual but what kids have worn since at least the 1950s. And the adults are acting like kids, too: the girls emoting excitedly about seeing someone special, the boys waiting in line stoically to hold their place until they can make a run for the prize.

Nor does this happen only at summer camp. Look around you in the grocery store. Fathers’ and sons’ clothing would be interchangeable but for the difference in size, and lots of other people also are dressed like kids. And look at what they’re buying: some basic provisions are there, but more often than not everyone in the family has been shopping like a kid in a candy store. Bottled drinks, chips, and other treats make sure that no one is denied their version of a Popsicle. Look again at the gifts that the parents have brought with them. Like the display of wealth that it displaced, American informality goes hand in hand with a culture of consumer consumption.

I’m wearing ragged shorts and a cheap t-shirt while I’m writing this, and I wouldn’t change to go to the store or just about anywhere else in town. I’m sure that we must look like hell to anyone with any sophistication. That stern looking guy in the middle of the picture, for example. His clothing bears some of the cultural shift evident in those on either side of him, but he’s still dressed more as an adult than a child. And he has the grim expression to prove it. The guy looks like he’d rather be at a board meeting and that he evaluates everything by the standards of corporate efficiency. Visually, he’s providing the contrast needed to feature the exuberance on either side of him. Culturally, he’s a relic.

When I was growing up in the 1950s, it was a big deal for my parents’ generation to be adults. For one thing, they really hadn’t been given a choice. Equally important, adulthood came with a lot of perks: sex, money, alcohol, the vote, and other privileges made it clear that while childhood may have been fun, adulthood brought a major shift in social status. Not surprisingly, one had to look adult, and a lot of effort went into that. Consumption was a part of the deal, but the focus was primarily on being or becoming bourgeois, not on indulging oneself. One also had to act like an adult, and that’s where things started to get complicated. Gender differences became very asymmetrical gender roles; being mature meant making conformity second nature; working hard while still doing without was justified because you were doing it for the kids.

The good news is that the past fifty years have been one of continuous liberalization. The American ideal of equality has been written into law and everyday life for many people in many ways large and small. Personal liberty and American individualism has led to a richly pluralistic society where many inhibitions were overcome in the pursuit of happiness. Informality in clothing and manners became an important part of this sea-change–an enactment of liberty and equality in the performance of everyday life. False impositions of status fell away at the beach and everywhere else. The status of adulthood was one of the casualties. It no longer carried many privileges, so you might as well be comfortable.

One of the interesting side-effects of liberalization on American terms has been the prolongation of childhood. Note that one rationale for having children now is that they make you grow up. I wonder about that. But it does no good to say “grow up” if that means becoming dour or continually calculative or stupidly bourgeois. And in fact childhood is not a time of freedom from work or anxiety these days, if it ever was. When kids are being driven to prepare themselves for a life of competition, being able to act like a kid may be one of the real benefits of adulthood.

Hope has been expressed that Obama’s victory in November will lead to a fashion shift back to the higher standards of the 1940s and 1950s–first with African-American youth, who then set the tone for the rest of us. It will be interesting to see if that happens and how it plays out. Those wanting change have a case, but they also have a lot going against them, not least the belief that happiness means being forever young.

Photograph by Todd Heisler/New York Times. The related story is here.

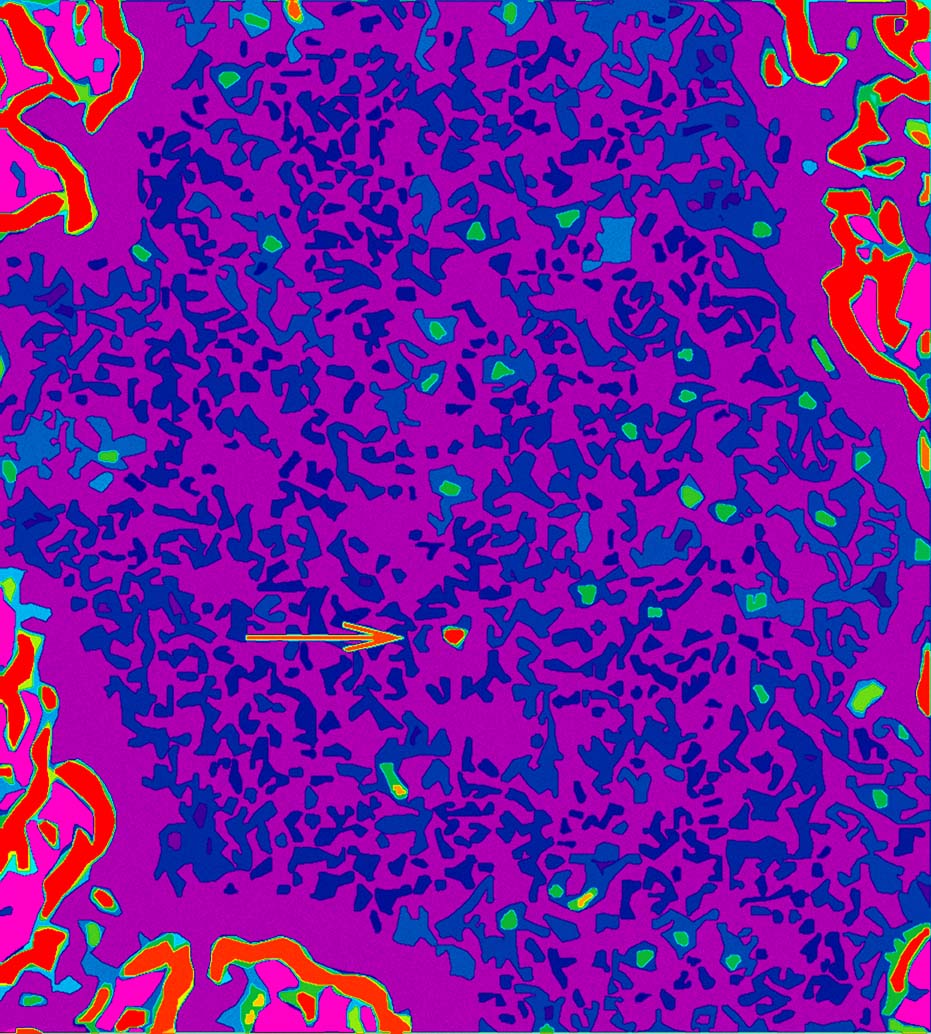

Seeing Atoms

We are pleased to welcome Ivan Amato as a guest correspondent. Ivan is the author of the wonderful book, Super Vision: A New View of Nature.

A century ago, some of the best scientific minds were still debating whether atoms actually existed. Although atoms had long been a fabulously useful concept for making sense of chemical and material phenomena, no one had actually seen them. Their existence always was inferred, not confirmed by way of direct observations. Even so, well before World War I, almost all scientists believed that atoms were real.

Since then, microscopists and instrument designers have been inventing ever more clever ways to visualize the material world on ever finer scales. For years now, scientists have been using tools with names like scanning tunneling microscopes (STM) and high resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) to image the regimented geometry of crystalline samples’ constituent atoms. It has been way easier to image individual atoms of the heavier elements of the periodic table, such as tungsten and gold, compared to the atoms of lighter elements. Hardest of all has been imaging the lightest and smallest atoms of all, among them hydrogen and carbon atoms. These are the atoms most associated with life and with the biological chemistry that underlies life, which is why atomic-scale imaging has largely been the province of physicists and materials scientists who make products such as industrial catalysts and semiconductors.

A team of researchers at the University of California at Berkeley, led by physicist Alex A. Zettl, has found a way to use a standard-issue transmission electron microscope (TEM) to visually discern individual atoms of hydrogen and carbon. A small number of these atoms that were lingering in the TEM’s sealed and evacuated sample chamber had drifted onto an atomically thin sheet of graphene–a molecular grid of carbon atoms in the geometry of chicken wire-that the researchers had placed inside the chamber. In the image shown, to which the researchers have liberally applied image processing tools to produce the colors, the hydrogen atoms appear as green dots amidst a speckling of blue, which essentially is background noise due to the graphene. A lone red dot, with an arrow for extra emphasis, marks the location of a single carbon atom.

In a more raw form, the data from the TEM appears as squiggly traces that indicate how much a beam of electrons impinging on the sample scatters as the beam hits different locations of the sample’s microscape. A computer then transforms this scatter intensity data into a two-dimensional, black-and-white pictorial image that corresponds to the sample’s atomic landscape. Then, with additional image processing requiring the applications of aesthetic judgments, that is, choosing colors, the original data finally becomes the abstract “painting” seen here, a painting that harbors what appears to be scientists’ first glimpses of individual hydrogen atoms by way of TEM.

Unlike directly seeing a flower in your garden or the web page you are viewing by way of your own eyes and brain, “seeing” atoms requires mediation–a TEM, a computer, and image processing tools-to render what is otherwise invisible visible. Yet, eyes and brains also mediate our seeing. They constitute evolution-honed instrumentation that senses photons from objects and processes these signals in a way that we experience as seeing. Directly seeing with eyes, then, might be thought of a singly-mediated seeing, whereas using tools like TEMs might be thought of as doubly-mediated seeing.

Credit for image: Courtesy Zettl Research Group, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and University of California at Berkeley. The Zettl group just published, in Nature (vol. 454, pp. 319-322), their first paper on the technique. The image above is not in the paper but is available at their web site.

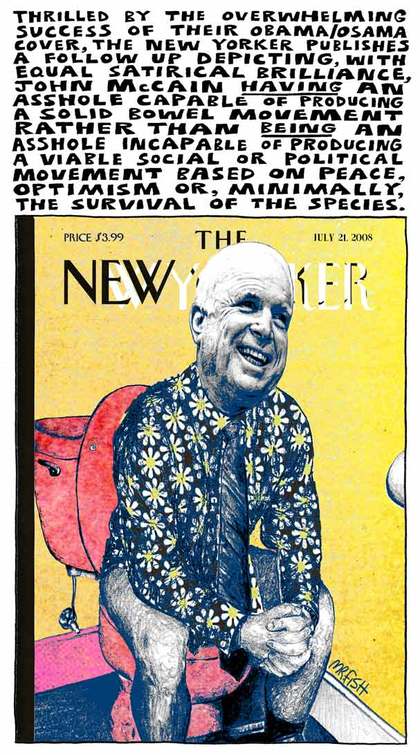

Sight Gag: On The John

Credit: Mr. Fish

Our primary goal with this blog is to talk about the ways in which photojournalism contributes to a vital democratic public culture. Much of the time that means we are focusing on what purport to be more or less serious matters. But as Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert often remind us, democracy needs irony, parody, and pure silliness as much as it needs serious contemplation. For our part, we will dedicate our Sunday posts to putting such moments on display in what we call “sight gags,” democracy’s nod to the ironic and/or the carnivalesque. Sometimes we will post pictures we’ve taken, or that have been contributed by others, or that we just happen to stumble across as we navigate our very visual public culture. Sometimes the images will be pure silliness, but sometimes they will point to ironies, poignant and otherwise. And we won’t just be limited to photography, as a robust democratic visual culture consists of much more. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.

Terrorism: Ya' Gotta See It To Beat It

The Big Picture has put together an awesome display of images that show how Beijing is preparing to secure the Olympics against terrorism while using the latest technology.

But, of course, with terrorists we know that the problem is you can’t always recognize them … and that is no small problem in China these days, as this daytime photograph of one of Beijing’s main avenues from the Guardian reveals:

Photo Credits: Xinhua/Fan Changguo/AP Photo; Reinhard Krause/Reuters

"All The News That's Fit to Print"

I used to think that claims of a “slow” summer news cycle were something of a myth. But the past several weeks have had me rethinking that position as I search for interesting and engaging news stories and photographs. Apparently the NYT is having a similar problem. Consider, for example, this photograph, which was featured on the front page of the NYT website for a short period of time yesterday afternoon:

What could the topic be? If you look close enough you might be able to tell that it is Invesco Field, the home of the Denver Broncos. But professional football is still several months away, and why would the NYT be featuring the Broncos in any event? Perhaps it has something to do with the high cost of sport tickets making it difficult for average Americans to attend professional sporting events. Or maybe it concerns the environmental impact of releasing thousands of balloons into the crisp, clean atmosphere of Mile High, Colorado.

All of these guesses would be wrong. Instead the article that this photograph anchors concerns the story—“rumored for days”—that the Democratic National Committee has announced that Senator Barrack Obama will accept his party’s nomination for the presidency at Invesco Field rather than at the Pepsi Center in downtown Denver. The reason, apparently, is that Invesco Field is a bigger “stage” that can host 75,000 people, whereas the Pepsi Center can only host 21,000. In short, moving the coronation of the party’s leader enables a much larger public spectacle—something, say, on the order of the Super Bowl … only one where “regular” Americans get to attend.

One might think that such a move would be welcomed by the networks who are always looking for ways to dramatize news events by making them larger than life, but in this case the network executives seem to be upset because they will have to “reconfigure plans long in the making,” changing venues and working outside. After all, and notwithstanding all of the sports metaphors used to describe the presidential campaigns, this isn’t really the Super Bowl; and besides, how can we expect the major news networks to adapt to the constraints of reporting on an event taking place in an NFL arena … it would be unheard of. (Maybe they should bring in ESPN to cover the acceptance speech.)

I really have to admit that my first thought upon reading this article was that someone from the Onion had hacked the NYT website and inserted one of their brilliant political parodies. The photograph, then, would be a sardonic comment on the political ritual of convention spectacles as little more than bread and circuses, or perhaps the journalistic impulse to anchor stories with photographs that only bear the most general and passing relevance to the facts being reported. But this is the NYT, right? And surely the “paper of record” has safeguards against such security breaches, right? And yet, truth to tell, after reading the last line of the NYT story I’m not so sure: “For its part, the Republican National Convention Committee released a statement dismissing the venue change as favoring style over substance. ‘Senator Obama and his fellow Democrats are more focused on stagecraft and theatrics than providing real solutions to the challenges facing our nation,’ the statement said.” And in case you don’t get the joke, click here.

Photo Credits: Doug Pensinger/Getty Images