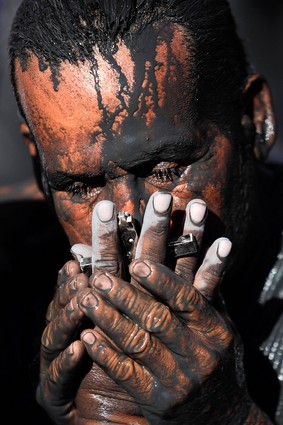

You will have seen the recent photographs of Pakistani lawyers demonstrating in the streets of Islamabad and then being punched, kicked, clubbed, and hauled off to jail. You won’t see what will happen to them in the Pakistani prisons, but that surely will include more brutality and probably torture. And what is incredible is that the demonstrators will have known that when they went into the streets. Their heroism is a rare and beautiful thing that has not been captured fully by any photo that I’ve seen.

But they are more than heroes–they are lawyers who have been working for years on behalf of the rule of law and liberal-democratic constitutional government. And they are less than heroes–ordinary people struggling to achieve something action heroes never see: the normal life of a modern civil society. That’s why I like this photo:

The New York Times caption said, ” Lawyers meeting on Monday at the bar association offices in the Pakistani capital, Islamabad.” This image captures both the pervasive weight of oppression and the incredible ordinariness of life as it is when people are allowed to live and work together without fear.

The steep odds and dark prospect before them are evident in the expression of the man in the foreground as that is reinforced by the serious faces all around the room. His expression shows that there are no good options, and that all that they have could be slipping away, and that he knows this. He has not caved, however: his forward posture, cocked head, and intense look suggest a man still capable of action, and the crowded presence of his colleagues all around the room is mute testimony to that resolve.

Heroism is seen in broad strokes, and what I love about this photograph are the many small details. The two thumbs touching in the right foreground, a practiced gesture of waiting. The sliver of leg showing between sock and pants cuff; the coffee cup and water glasses abandoned on the table; the dark furniture and wood paneling seen in almost every lawyer’s office in the world. The clothes and decor are nice–Pakistan does have a middle class—but they are above all conventional, the ordinary background of modernity.

What unites these opposing attitudes of normalcy and oppression is the fact that those in the room are waiting. Images, like texts but often even more so, are condensed interactions. If nothing else, they structure a relationship between the subject of the picture and the viewer; often they depict patterns of interaction that can resonate outside the frame. The people in this photograph are waiting, and that can evoke many contexts: they could be in a doctor’s waiting room or a funeral parlor or a green room or a bomb shelter. They could be waiting because someone is late or because someone is missing. They could be hoping that late results would reverse the tide of electoral defeat, or for the verdict in a court case, or for the results of an exam or an interview. They could be at a consulate anywhere in the world. If there were no exit, they could be in Hell.

Thus, the photograph is above all else an image of waiting, and with that it evokes both terror and a promise. The terror is that they are already doing what they will be doing in prison: waiting for something much worse to come. The promise is like that sliver of bare leg: the hope that some day, if others would join their fight for a liberal democratic society, they would be able to enjoy a world where one is secure enough to suffer only boredom and the occasional fashion mistake.

We need to continue to see the familiar images of street demonstrations, but we need photographs like this one of the silent spaces of political life. Then perhaps the professional class in this country can see themselves in the picture. Over here, lawyers know they are not “hired guns” or “ambulance chasers.” I hope they can look at this picture and understand that their colleagues in Islamabad are not “extremists and radicals.” They are heroes, but we should stand by them because they are ordinary people who should not have to be heroic.

Photograph by John Moore/Getty Images.