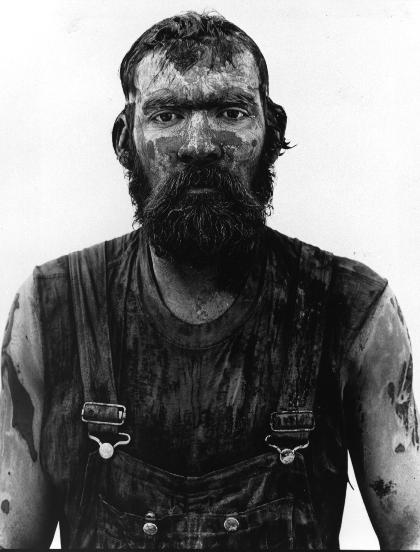

From the redwood forest to the gulf stream waters and from sea to shining sea, images of natural splendor have loomed large in American national identity. The appear everywhere from car ads to movie vistas to those framed Ansel Adams’ photographs that you see in doctors’ offices. Images of the national landscape also appear periodically as photographs in the daily paper. This one caught my eye yesterday while clicking through the photos of the week at the Chicago Tribune:

Why did I stop and look? Because it is beautiful. The strong blues and turbulent contrasts of the sky flow smoothly over the golden field of grass. The herd of horses moves nonchalantly across the field despite the powerful forces gathering above them. Like the trees on the right, together yet each standing independently, they need not fear an afternoon storm. The photograph was taken “near Troy, Idaho”; that “near” is a linguistic marker of the Western sense of open space. The scene is a reminder of the sublime promise of the American West, where all can live both free and in harmony with nature.

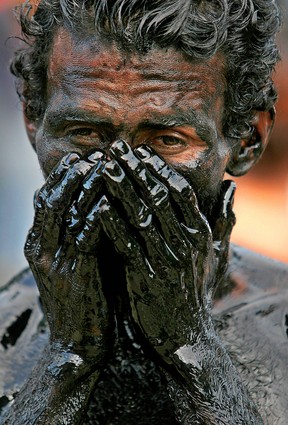

That’s the promise. Other photographs document the underside of the dream. Richard Avedon created a brilliant series of images to challenge the myth of the empty landscape. His images of miners, migrant workers, and others provide stunning evidence that the West is also a place where people live lives of hard labor. These images reveal domination, exploitation, and the wastage of human life on behalf of the production of wealth, but they also reveal something not found in the natural landscape: dignity.

This is a picture of Red Owens, an oil field worker. This, too, is the American West. Free but not free, close to nature but used up by the physical work of extracting natural resources from the earth.

The first picture appeared during a week when the papers were reporting deaths from a mining accident in Utah, and a swath of destruction unleashed by thunderstorms across the Midwest. The mountains bring more than scenic views, and nature is no respecter of persons, or cities, or nations. We cannot serenely move across the landscape to better pastures.

The task of rebuilding community has to include far more than a change in perspective. In fact, I think we need both photos. And they can do more than provide sunny distraction or a grim reminder. It’s a stretch, but the first photo brought to mind a phrase from Winston Churchill’s “finest hour” speech: “If we can stand up to him (Hitler), all Europe may be free and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands.” If a photograph of beautiful uplands can be an image of freedom, then perhaps we are more likely to aspire to that. Likewise, the second photo can evoke the remainder of Churchill’s statement: “But if we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new dark age made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science.” We need not bash science, but the truth is that the control of nature, like nature itself, can be used for good or ill. A free people cannot live in a state of nature, but freedom may depend on how they understand their relationship to nature and to each other.

Photographs by Steve Hanks, Lewiston Tribune, August 22, 2007, and Richard Avedon, 1980/1985. See In the American West.

Winston Churchill, “Their Finest Hour,” speech to the House of Commons, June 18, 1940.

Thanks to Michael J. Shapiro for bringing the Avedon photographs to my attention in his fine essay, “The Political Rhetoric of Photography,” chapter four of The Politics of Representation.