The recent G-20 meetings were the occasion for thousands of anarchists, and anti-capitalist, anti-war, and pro-environmentalist protestors to converge upon London, as has become something of a ritual for such international events. No one seems to know exactly how many protesters there really were, though various media reports range from 20,000 to 35,000. The Guardian reported that 5,000 police were deployed for the event, most of them in the financial district. By conservative estimates, then, the ratio of police to protesters was somewhere between 1:4 and 1:7. Protesters, of course, are meant to be seen, why else show up! And most of the pictures reported by the mainstream media obliged by toggling back and forth between images of the carnivalesque and the clash between protesters and police, often resulting in dramatic images of bloody violence.

We can find all of this at the Boston Globe’s “Big Picture” website, but we find there as well an additional set of photographs that points to a different and more interesting phenomenon: images that accent what Ariella Azoullay refers to as the “civil contract of photography.” The citizenship of photography that she calls attention to is animated by the logic of photography—an agreement as to the relationship between the photograph and “what has been” or what might be in the image—and the ways in which it functions as a mechanism of social interaction (and control).

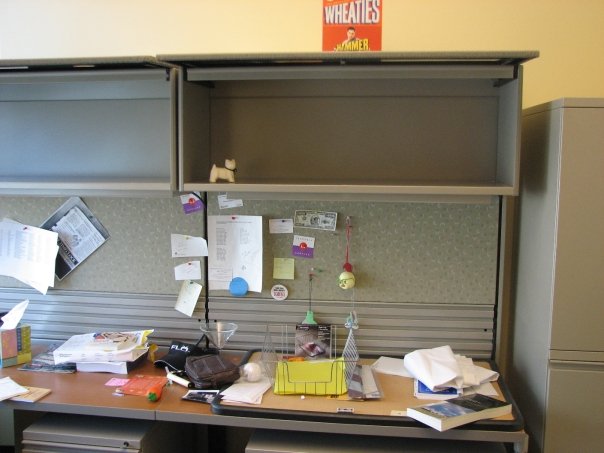

The scene above is a wall of CCTV screens in a command and control center in London from which the police can monitor live security feeds of “prominent areas” of the city. It has an Orwellian quality to it, to be sure—Big Brother is watching—not least because the heads viewing the scene are back lit and thus cast in dark and foreboding shadows that provide a stark contrast with the daylight of the screens. As such, the image directs attention to its own technology, and thus the visual grammar that animates it; in short, what we are looking at is itself a photograph—a visual representation of the command and control center once removed—that relies upon the logic of photography as it displays a site for interpretive resistance to the mechanism of surveillance that is being exacted by the state precisely by making it transparent.

Nor are the broader implications of the civil contract of photography lost on the protesters themselves, who were armed not with guns or nightsticks or other riot gear (like the police) but with cameras.

There are numerous photographs that make the point (see photos 11, 12, 19 and 20 at the Big Picture), but I like this image the most, in large measure because of how the police appear to react. Their purpose is to protect the bank from the protesters, and of course they are doing that, but it all seems so out of proportion: they are larger in number and size, and in any case they are girded for battle; the protesters sit and squat awkwardly on the ground as they take pictures or stand about nonchalantly with their hands in their pockets. On the face of things they certainly don’t seem to be much of a threat. Change the context just a bit and we might imagine them as tourists out for a day in the city. And that is precisely the problem for the police who seem literally stopped in their tracks, as if they don’t quite know what to do. Indeed, it could be a scene out of a Monty Python skit. Should they pose for the camera or charge? Caught in the gaze of the lens—and thus the implied civic contract of the photograph—their power seems mitigated, if only for a moment. But that moment is enough to shift the ground of agency and control, if not for the people in the image itself, then at least for those who see the photograph, i.e., those cast in the role of spectators who, by the virtue of the civic contract, are nevertheless called upon to render judgment.

*The fragment here is from Heidegger and reads in full, “The fundamental event of the modern age is the conquest of the world as picture.” It appears in “The Age of World Pictures” published in Electronic Culture, ed. by T. Druckery. New York: Aperture, 1969. I came across it in Ariella Azoulay’s “The Ethic of the Spectator: The Citizenry of Photography,” Afterimage, September/October 2005, 39. For a more detailed discussion of her ideas see The Civil Contract of Photography, MIT Press, 2008.

Photo Credits: Kirsty Wigglesworth/AP, Adrian Dennis/AFP/Getty Images