I am suspicious of references to “the Arab Street,” particularly when the phase is applied–as it often is–to nations and other vast swaths of territory that are not Arab or not exclusively Arab. Several years ago Christopher Hitchens declared that it was a vanquished cliche, but he was misusing it himself to justify the rush to war by the Bush administration. And he wasn’t speaking of its persistence as a visual convention.

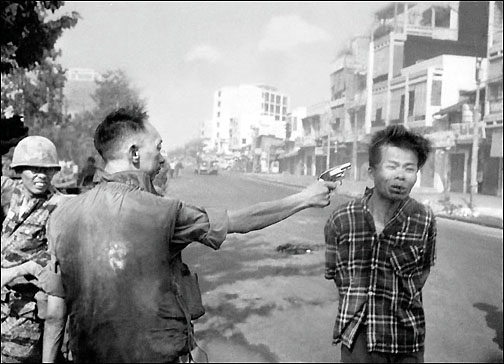

The caption of this photograph at The Guardian says only, “Nowruz celebrations in Afghanistan.” Nowruz is the name of the Iranian New Year, which is celebrated in a number of countries by people of several faiths. The baskets of dried fruits eaten during the holiday provide the only visual connection to the colorful festivities, and you have to know more than the paper tells you to see that. For many viewers, this will a thoroughly conventional image of the Middle East.

That image is one of throngs of working class men massed together in the street. What little business is there is in the open air markets lining each side of the densely packed urban space. We see small batches of everyday goods on display–probably to be bartered for, no less. The open baskets of food are a sure marker of the underdeveloped world. (Imagine how many packages it would take to wrap up that fruit for sale in the US.) Everything fits together into a single narrative, but the masses of men and boys make the scene politically significant. This is the place where collective delusions take hold, where mobs are formed, and where unrest can explode into revolutionary violence and Jihad.

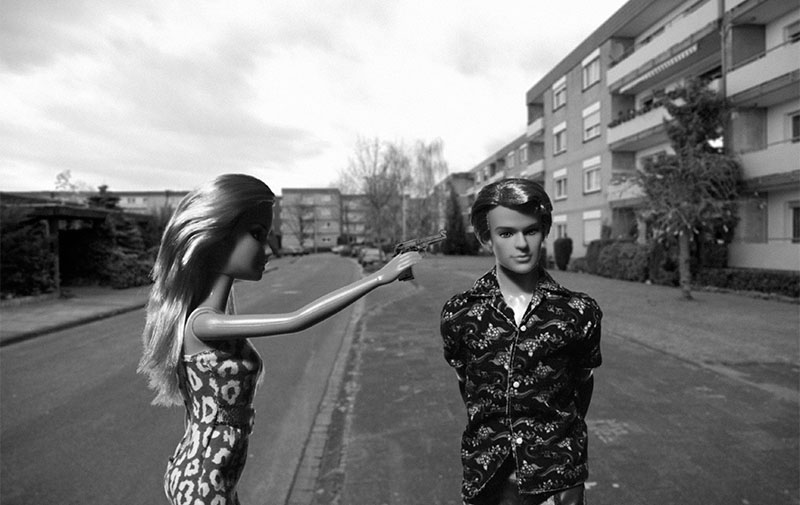

Which is why I get a kick out of this photograph of another Nowruz celebration.

The caption reads, “An Iranian man skewers chicken for grilling as he picnics with his family.” My first thought when I saw the image was to check and make sure it wasn’t taken in Chicago. This also is a very familiar scene: grass, blankets, families and friends, plastic containers of food, dad getting ready to do the grilling.

What is astonishing is that I was able to see them at all. A typical summer holiday photo becomes a radical disruption of Western visual conventions when taken in Iran and shown in the US. Of course, it wasn’t shown in the US: this, too, is from the UK paper.

In this photo, there is no Arab street, and no Iranian masses dominated by Mullahs and demagogues. A middle class tableau reveals that so much of what is in fact ordinary life for many people in Iran and elsewhere in the Middle East is never seen in the US. And it isn’t seen because it doesn’t fit into simplistic categories, outdated stereotypes, and a dominant ideology. All that is shown and implied in the cliches is of course also there, but it is there as part of a much more complex and varied social reality.

As evidence of how things might appear a bit different, notice how seeing the second image can affect perception of the first one. In the second, it seems evident that the family is posing for the photograph. They’re doing exactly what they would have been doing but now with the additional, amused awareness that it is, for a moment, also an act. And sure enough, if you look back to the first photo, you can see the same thing. And if you can see that, they no longer need appear as a mass, or poor, or threatening, or anything but people enjoying a holiday. Much like people in the US were doing this past weekend to celebrate St. Patrick’s day, thronged together, in the street.

Photographs by Natalie Behring-Chisholm/Getty Images and Behrouz Mehri/AFP-Getty Images.

12 Comments