There’s been a lot of talk lately, including a post at this blog, about accuracy in photojournalism: How much can a photograph be adjusted artistically and still be considered true? How much detail should the captions provide, and in respect to what questions or values? Despite strong and often heated disagreements, most commentators across the spectrum seem to assume that the reportage could be thoroughly accurate, specific, relevant, and otherwise up to the task of giving the public what they need to form sound judgments about current events.

Let me now suggest that sometimes we are better off without that assumption. More to the point, one of the jobs that photojournalism also has is to remind the public how much eludes understanding. Thus, some of the photos (and their captions) are good journalism because of how they show us the limits of what can be seen.

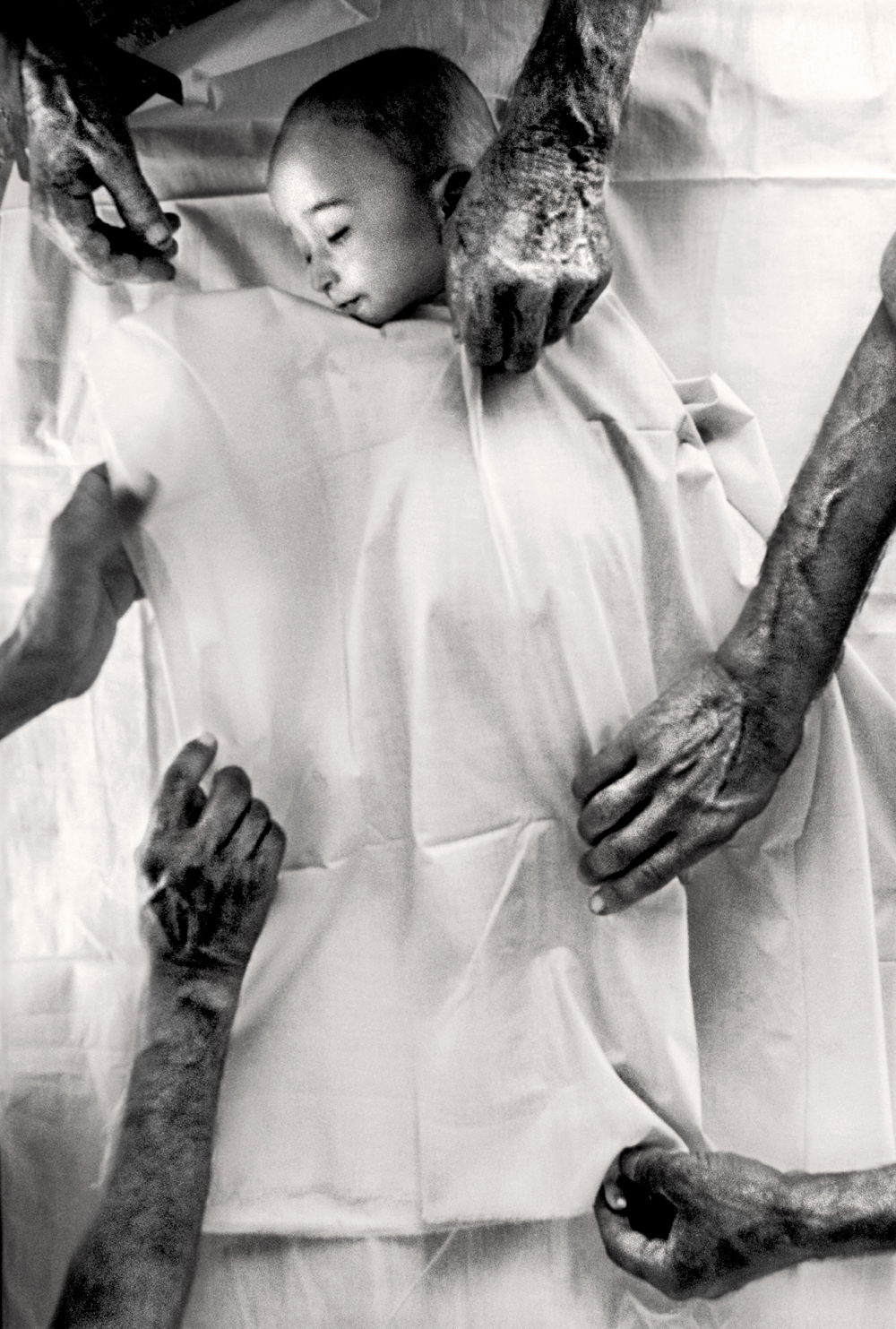

The caption at Time said, “May 13, 2013. Syrian army soldiers take control of the village of Western Dumayna, some seven kilometers north of the rebel-held city of Qusayr.” The “seven kilometers” suggests that we are being given a precise description of what is happening, even though you can’t see any of that fact in the photograph. Many viewers might feel adequately anchored at that point and so look a moment longer and then move on. But wait a minute: is this an image of “control”?

Horrific flames and dark, thick smoke billow from the other side of the wall. The open doorway reveals only blackness, as if a void lies within. A swatch of fire has dropped on the outside of the wall, near which a lone soldier is about to enter through another doorway into the interior. The soldier is controlled, disciplined, brave, and probably used to working amid the roiling destructiveness of battle, but he also is a marginal figure in the composition and appears almost furtive as he enters what is effectively the back stage of this set. Set in diminutive contrast to the powerful flames, he can’t be the locus of control. Likewise, additional reportage (the full caption not included at Time) tells us that a Syrian advance had gained a strategic advantage and cut supply lines in Qusayr, but that larger sense of command and control also is not evident here. In fact, this image seems to be very much a picture of something closer to chaos.

And that may be the point. I’d say this photograph shows just how “control” is an abstraction that is imposed on the material destructiveness of war. Being abstract doesn’t mean it isn’t real, but it does mean that it depends on a certain distance from the flames. Likewise, describing the battle in terms of control is of course very much to the point of the fighting, but it also encourages denial of just how terrible life can become on the other side of that wall.

Seen in this light, the wall now assumes a double meaning. It is still a structure about seven kilometers north of Qusayr, but it also can be a symbol of how the truth of the matter on the ground might lie forever behind a barrier. Walls stop vision, and here it seems that the action that really counts lies on the other side of that thick, stony, silent wall. This is not just a blockage, however, but a reminder of how vision and with that understanding is always partially blocked. This wall now speaks eloquently of the limits of our understanding: we no more understand the battle than we did when we were told that it was about “control,” but now we have a visual emblem of that limit on our comprehension.

In marking how war can exceed representation, the image also can say something about this war. Readers of a certain age will recall the infamous statement that “we had to destroy the village in order to save it.” One can’t help but wonder if the same holds for Syria, which is being laid waste. If we can’t see a reason for the destructiveness, it could be because one no longer is there. As Suzy Linfield has said, violence today too often becomes untethered from any ideological rationale and political administration. The result is not something that later can be honored as justified sacrifice for the nation or the cause, but only awful cycles of violence that burn through civilians like firewood.

Thus, by recognizing how this war exceeds our understanding, we also can consider how that is not merely a failure of perception. War itself may lie hidden behind that wall. Raging destructiveness without purpose or limit, fueled by ignorance and protected by abstraction, it can lure anyone to cross that threshold, only to devour them in the darkness.

That compact with oblivion is all the more reason to supply as many photographs and words as one can to show what must be shown. But it is equally important to remember that none of us can fully know the truth, and how war can count on that. That is no reason for despair, however. Even when at the limits of comprehension, the ideal of peace is always on the horizon, waiting for those who will start walking in that direction.

Photograph by Joseph Eid/AFP-Getty Images.