You might have heard that there was a shooting in midtown Manhattan late last week. It was in all of the papers and on the nightly news. Of course, then again, such events seem to be routine so maybe you missed it. The perpetrator got off five rounds, all aimed directly at his target; the police got off seventeen shots. Nine bystanders were hit with bullets. Do the math.

The photographic record of the event ranges from the somewhat clichéd representation of yellow and blue police line tape and numbered crime scene markers shot from on high and at a distance to mark the official response to a somewhat voyeuristic image of a dead body resting in a sea of red blood to the absolutely bizarre snapshot of smiling tourists (from France, no less) posing in front of the scene where the carnage too place. But it is the photograph above that tells the story that really needs to be told.

The woman, Madia Rosario, is one of the nine innocent bystanders hit by police bullets (that’s right, all nine were wounded by police bullets or ricochets). She is thankfully in stable condition, as are apparently the other eight bystanders who were wounded. But what should concern us is that she and the others were shot at all. There have already been calls to investigate whether the officers were following regulations when they discharged their weapons with bystanders at risk, but there is a different point to be made. Or maybe two.

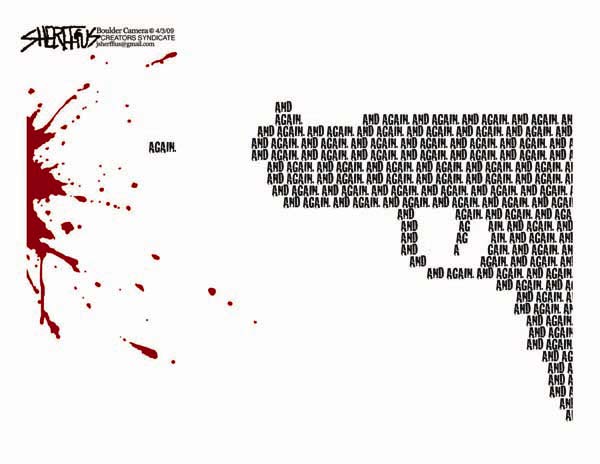

The first point is that this is just one more of a continuing—weekly if not daily—litany of such shootings, each of which is treated as if it were an entirely individual and isolated event. A disturbed individual goes berserk and shoots up a school yard or a campus or a church or a movie theater. As one of the bystanders hit by a police bullet put it, “You know, stuff happens.” But of course these are not isolated events, for what connects them quite palpably is the simple fact that in each case the perpetrators all had too easy access to automatic or semi-automatic weapons. There is no easy way to represent that connection photographically, and so we resort to commonplaces that individuate the problem by emphasizing the perverse psychology of the perpetrator and/or visualizing the official response. But of course in countries with more restrictive access to such weaponry events like this happen far less frequently. On this point the facts are incontrovertible. Once again, do the math.

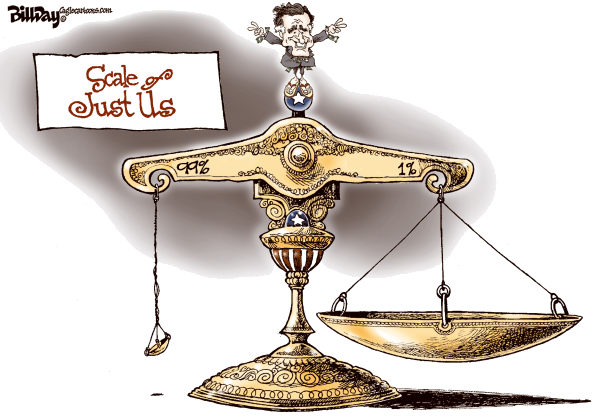

The second point is really a response to those who claim that everyone will be safer when we all have guns and can thus protect ourselves from such violence and bloodshed. But the photograph of Madia Rosario suggests perhaps otherwise. The police are enjoined never to “put civilians in the line of fire.” And more, they are trained in how to respond to crisis situations in which chaos reigns and human behavior is animated more by fear and the rush of adrenalin than reason or common sense. And on par they do a pretty decent job. And yet for all their training and preparation, “stuff happens.” One can only imagine what stuff would happen if bystanders not trained in crisis management of any sort were carrying weapons and started shooting. Just do the math.

Photo Credit: Uli Seit/New York Times