Credit: Bureau of Labor Statistics, September 2009

Sight Gag: You're In Good Hands …

Credit: Branch, San Antonio Express

“Sight Gags” is our weekly nod to the ironic and carnivalesque in a vibrant democratic public culture. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course, we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.

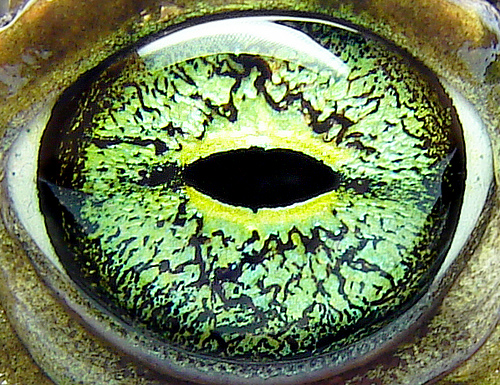

Encyclopedia of Life

If you think Wikipedia is a good idea, you might also want to look at the Encyclopedia of Life. This is an online collaborative project to document all living species. If short on taxonomic skills, you might still be able to enjoy and perhaps contribute to the photo archive. Here’s looking at you, kid.

Photograph of the eye of a European Green Toad, Bufo viridis, © Matt Reinbold via the Encyclopedia of Life media image page.

Monumental Visions

When raging wildfires threaten a city, the imagery quickly acquires an allegorical tone. Apocalyptic horizons suggest that much larger catastrophe looms, and civilization itself can seem exposed, unprepared, unprotected. At that moment, the public art of photojournalism becomes capable of both revealing vulnerability and meeting the need for reassurance. Like this:

As fires engulf one side of Athens, Greece, the Parthenon arises above the city in magnificent splendor. Marble bathed in electric light, the monument anchors the image. One could almost image a cosmic battle between firestorm and enlightenment. Culture rises up against Nature, a glorious past against a chaotic future, continuity against conflagration.

In between lies the city. Although hundreds of thousands of people will live and work there, it is subordinated between the monument in the foreground and the ring of fire on the horizon. Set in a natural crater, in the middle distance, with small lights scattered across it as if they could wink on and off, the city seems to lack both significance and power. Actually a dynamic achievement greater than any monument or natural event, here its fate seems poised between two alternatives, one of which is no longer possible while the other is terrifying. It becomes merely a firebreak between past and future, between a lost world and the task of staving off disaster.

You may have to look at the image for awhile to notice the city at all. The monument dominates the scene, and there is reason to be suspicious of its prominence. Is Athens only the conservator of the Golden Age of Greece (and, according to the standard narrative, the West)? Are we to be reassured that the shrine still stands, despite whatever havoc is being experienced by ordinary people whose houses are in the fire zone? If the photograph reveals a deep tension between civilization and catastrophe, it also may be helping some return to a false sense of security.

One might ask, isn’t that what monuments are supposed to do? Yes, but then there is this image:

I won’t dote on this unusual shot of the Washington Monument, but it is a remarkable example of how the conventional view–and experience–of a public work can be altered by a change in angle and lighting. Instead of the white tower rising in sublime simplicity amidst the capitol city, we see what could be ancient ruin. Stragglers wander about the obelisk on a dark plain under a threatening sky. We could be on a moor near Stonehenge as pilgrims pass by on the way to another destination. The pennants in the background could be from a temporary fair in some dark age yet to come. Again, the future seems much less promising than the past. The difference here is that, instead of using the monument to anchor collective experience against disruption, now the public icon has been turned against that conventional experience. Instead of security, the monument anchors a sense of foreboding about the national project.

Two monuments, two visions. The photographs in each case contain no news, but they do provide allegories of collective life.

Photographs by Milos Bicanski/Getty Images and Jewel Samad/AFP-Getty. For other NCN posts on wildfire images, go here, here, and here.

Bearing the Public Pall

Bearing the pall is an honored ritual in western funerary traditions according to which typically the most intimate friends and family members of the departed carry the casket that cloaks and contains the bodily remains. Until recently I thought of this as a rather instrumental ritual, activated largely by the pragmatic need to transport the body from one place to another in solemn and decorous fashion. This past spring, however, my mother passed away at the age of 83 and I came to realize the larger symbolic significance of literally touching the coffin, of making physical contact with the deceased, even if only by proxy and separated by the ritualistic container. I can’t say that I have the words to describe the actual feeling accurately, but there was something powerfully transcendent about it—almost as if I was making contact with a different plane of existence.

My experience was personal and private and I haven’t discussed it with anyone until now. Nevertheless, I was reminded of it by this photograph of Senator Edward Kennedy lying in repose at the JFK Presidential Library in Boston. The individuals kneeling at the coffin are five female family members, but in the visual tableau of the photograph they function as faceless surrogates for the thousands of anonymous members of the public who stood in line for hours just for the opportunity to pass the casket on the other side of a velvet rope and to pay their last respects to a life dedicated to national public service. The photograph underscores the solemnity of the occasion—heads bowed, hands folded, and notice how the pall is illuminated in a space otherwise shrouded by shadows cast by the backlit scene—but more than that it channels an ineffable, transcendent, affective sense of belonging that is arguably essential to communal life, animated here by decorously “touching” the coffin with our eyes.

The photograph above was the first image in the NYT’s “Pictures of the Day” for August 25, 2009. The second picture in that slide show was of the funeral procession for Abdul Aziz al-Hakim, an influential Shiite theologian and the leader of the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq who had died of lung cancer.

The NYT employs the two photographs to make the point that “very different” leaders—one quintessentially western, the other quintessentially eastern—were mourned in “very different ways,” contrasting the rational and decorous “solemnity of the public farewell to Senator Kennedy” as “thousands of visitors continued to line up to pay their respects,” with the unfettered “emotion of the public farewell” to Abdul Aziz al-Hakim marked by the “thousands [who] poured into the streets amid tight security.”

And indeed, the normative differences and implications of the two photographs are surely pronounced, as one displays a scene that is apparently stately and reserved, a modicum of order and restraint, while the other purports to reveal a dangerous mob “pouring into the street” and warranting “tight security.” In one image the facial markers of emotional expression are hidden from view as the faces of the individuals cannot be seen, either turned away from the camera and directing attention to the coffin or veiled by distance and dark shadows. In the other image, however, shot in the harsh light of day, facial expressions of intense emotion are prominent and pronounced, not least the man in the very center of the image who appears to be bearing much of the weight of the coffin and crying out in grief. And there are other differences as well, as one image genders the public it displays as passively female, the other aggressively male.

And yet for all of the differences what stands out most in need of comment is the profound similarity between the two photographs as each indicates a ritual of mourning predicated on making a direct, affective connection between a surviving public and its deceased leaders as a performative, transcendent marker of civic identity. Call it “solemnity” or call it “emotion,” the simple fact is that communal life demands affective connections. If we are going to come to terms with the profound tensions between east and west we might not find a better place to start than in acknowledging and taking account of this radical similarity.

Photo Credits: Damon Winters/NYT; Loay Hameed/AP

Sight Gag: C-I-A! C-I-A!

Credit: Aislin, The Montreal Gazette, 8/29/09

“Sight Gags” is our weekly nod to the ironic and carnivalesque in a vibrant democratic public culture. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course, we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.

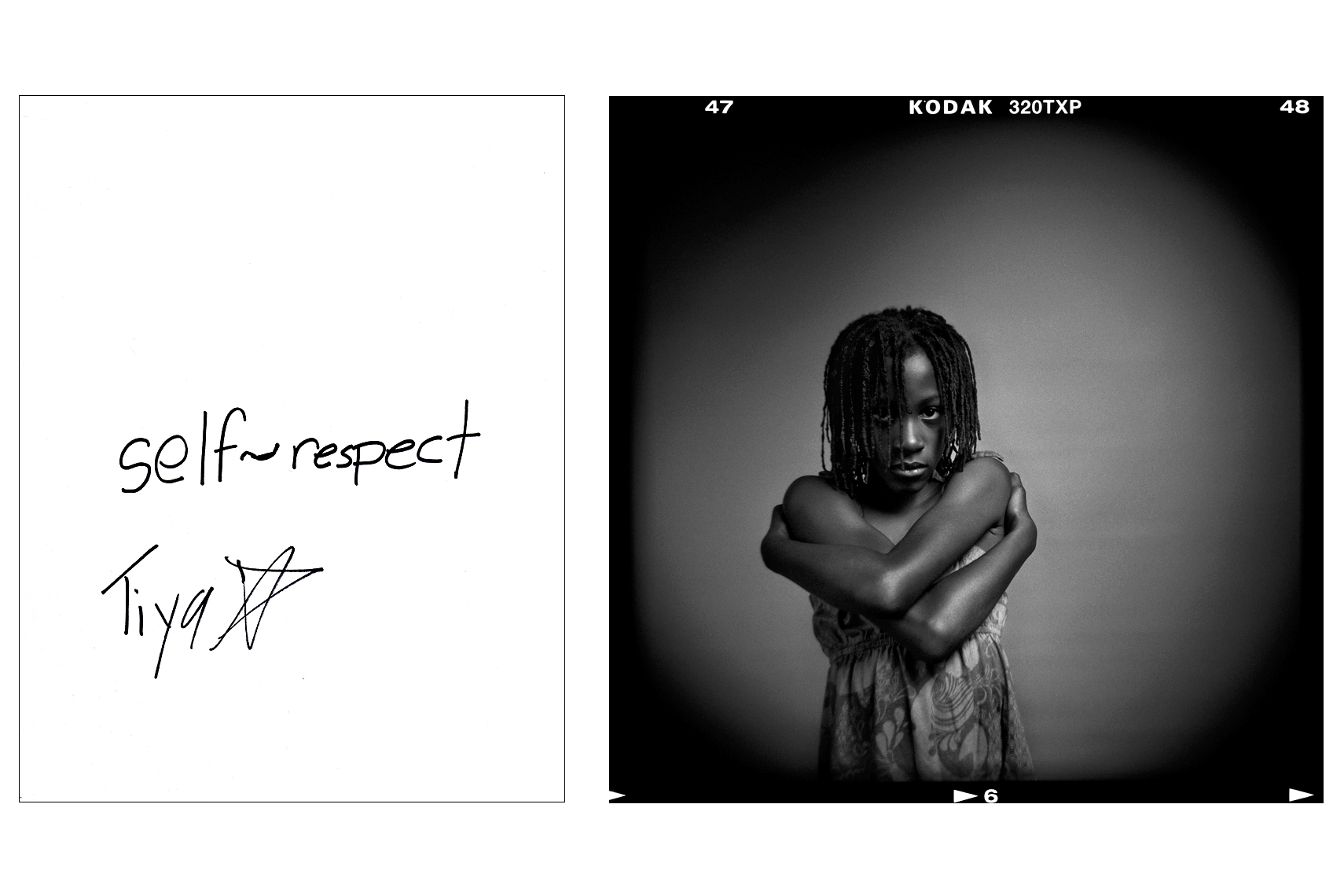

The People Project

Morgan Hager has created a show called The People Project.

“There are a myriad of challenges facing the human race today. The People Project attempts to define the challenges facing humanity as a whole by examining the views of the individual. Through compelling images and the thought provoking words of his subjects, Morgan Hagar has begun an ambitious ongoing project in hopes of answering one question… What is Humanity’s Greatest Challenge?”

This is an ongoing project still in its initial phase. Hagar’s home page is here; his blog is here.

Separate Visions in the Same Place at the Arctic Edge

Photography (and neither painting nor film) is the nearest artistic source of contemporary conceptions of the natural sublime. And with good reason:

This image just about stops my heart. It is majestic and serene, austere and wild, menacing and yet perfectly balanced. And far more than its informative caption: “Icebergs float in the calm waters of a fjord, south of Tasiilaq in eastern Greenland August 4, 2009.” (To get the full effect of this Arctic vista, see it at The Big Picture.) The broad, encompassing horizontal field seems to expand infinitely, and yet the sharp angle of the berg in the foreground is paralleled by the ominous thunderhead on the left, as if they were two tectonic plates shearing across each other. Between them the light of a fading sun recedes to the vanishing point. Could Valhalla be too far beyond that horizon?

This scene is so elemental–water, air, earth, and fire–that it seems to bring us to the edge of reality itself. And yet we are the supernatural beings here: for we see but are not seen. And we can view the cold, harsh elements at the world’s edge because we stand safely on some unseen platform–most likely, on a boat.

This photograph of the port of Nuuk on July 6, 2009 is in many ways the opposite of sublime. Instead of elemental and awesome, it is crowded, busy, varied, jumbled–even when stilled, supposedly at rest, it is a riot of color and variation. Boats of every size, shape, and purpose are wedged together. Nature’s dangers are still implicit in the scene: the boats huddle together because the barren hills will provide little protection from northern winds whipping down a narrow channel. But this is an image of vitality, of life thriving far beyond moss on a wind-swept rock.

Although no people are visible in this picture, we are everywhere: bustling and creative, but still having to hug the shore. The welter of masts, poles, cranes, and wires makes a mess of the visual field, but those boats are the only basis on which we can even see other images of natural beauty. One problem is that these two visions are kept apart, even though they come from and need to coexist in the same place. There are many factors in this enforced separation: social, political, and economic practices not least among them. We need to consider, however, how the artistic medium itself is part of the problem.

It remains easy to see nature in one place and human activity somewhere else as long as each is sequestered within its own visual field. To have both–in reality, not merely as images–we have to think carefully about how we use our images. Without images of natural splendor, an important incentive for conservation is lost; without sustainable economic and social practices, the natural environment will continue to be ruined while images serve a psychology of denial among those otherwise separated from the leading edge of destruction.

Fortunately, photography also can be a part of the solution. Just as the individual photograph can both inspire (think of the image of the whole Earth floating in space) and mislead (as when nature and culture are placed in separate still images), photography can help lead the way to imagining how to integrate separate visions. Sound ecological design has to include both the sublime and the practical, but not in separate places.

Photographs by Slim Allagui/AFP/Getty Images and Bob Strong/Reuters.

Nature in the Global Petri Dish

You might wonder what you are seeing in this photograph:

Look closely, and you will see a clump of trees. Some might also recognize the even rows of high-tech, monocultural agriculture stretched across the plain. But I’ve given too much away, as you also could have seen a clump of mold or cells bunched together in some microscopic field. Beneath the surface, one might also “see” some more elemental social form such as herd animals pressing together for warmth or even an ark adrift in barren sea. Whatever it is, it is visually striking: one blot of rich green on a uniformly reddish-brown background etched with small modulations in black. Scale becomes elastic while form and color dominate in any register. There is something basic here, but what?

Perhaps some content would help. The caption in the New York Times read: “Small islands of forest dot the landscape of farms and ranches, fulfilling regulations to maintain percentages of native forest on agricultural properties. Driven by profits derived from fertile soil, the region’s dense forests have been aggressively cleared over the past decade, and Mato Grosso is now Brazil’s leading producer of soy, corn and cattle, exported across the globe by multinational companies.”

OK, it is a photograph of trees in a field. Trees saved to maintain a forestation quota, in a field of soybeans produced for the international commodity markets. The additional information and the political subtext are helpful, but a problem remains. Note how the photo’s ambiguity in scale is also there in the text. We are seeing something “small,” and also something that extends “across the globe.” And, sure enough, the story behind the picture is one that identifies the tension between localized benefits and global costs. Life might be simple if one could focus exclusively on one dimension or the other: manage the forests for the planet, or allow economic development wherever possible. But, of course, the problem is that both are needed. One has to be able to see both locally and globally, a bifocal vision that itself does not come cheap.

Some might argue that the picture is unfair. It looks as if only the trees are natural, whereas in a few months the entire field also would be a vibrant green. Frankly, “nature” is becoming an outmoded term, and protecting nature or biodiversity or carbon dioxide levels or any other ecological value involves both technological savvy and a recognition that life is everywhere, even in burning forests for commodity cropping. The photo is not so much fair or unfair, however, as it is profound. It captures something essential, a sense of what is at stake. That small island of trees can stand in for everything from a tiny cell to the planet itself, and the point is always the same: no matter what the scale, life on earth is a small, precious island amidst a void.

The image is ironic as well: trees having no need of human intervention evoke something like sympathy, whereas the field is an achievement of human productivity that will produce historically astonishing yields capable of feeding millions. But, of course, it’s not that simple. The fields will wither if the carbon dioxide levels get out of whack, and the deeper irony is that what feeds us can kill us. Just as indigenous peoples in the Amazon basin learn to discriminate poisons, medicines, and foods carefully in the forest, moderns need to learn to do the same in respect to their remaking of the forest. In each case, one needs to learn to see, but not in the same way.

In this case, the photograph provides one lesson in how to see modern development: as if cultured for observation, both up close and from a distance, on behalf of sustainable growth, and capable of extinction.

Photograph by Damon Winter/The New York Times.

Sight Gag: The New Colossus For the 21st Century

Credit: R. J. Matson/St. Louis Post Dispatch

“Sight Gags” is our weekly nod to the ironic and carnivalesque in a vibrant democratic public culture. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course, we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.