By guest correspondent Daniel Kim

Peer into the small, circular opening of just about any camera’s viewfinder, and you’ll see the familiar, rectangular frame through which the photographer composes her image. There exists, however, within contemporary point-and-shoot cameras, another frame that is often relegated to the background—quite literally. This LCD frame is positioned behind the camera and it provides the photographer with an instant relay, or feedback, of what unfolds in front of her.

Photojournalists employ a pejorative term called ‘chimping,’ which denotes the act of admiring one’s own photo directly after each shot. The term is meant as a critique of the photographer who may otherwise miss an important shot within the course of his self-admiration. I do not share in this criticism, but I do want to discuss the chimping that is now ubiquitous in snapshot photography. My concern—or hope, rather—is that we can transform how we think about, and therefore, how we go about the process of looking at one another.

If we are to consider how photography can act as democratic speech—as a practice adding to the richness of citizenship—then the snapshot photographer should be capable of a degree of reflection, during the act of taking the photograph, that we have yet to witness with any regularity within the culture of everyday life.

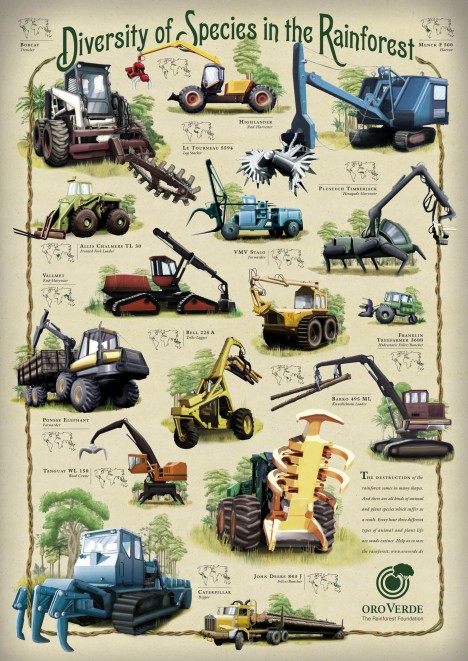

The photo above can be read as part of a continuing critique on photography’s affair with the spectacle. But the predictability with which this phenomenon now occurs, be it at government inaugural or rock concert, reveals just how entrenched the habit of seeing through a screen becomes to those determined to capture rather than look. Taking a step back, Magnum photographer Elliott Erwitt contemplates the sight in front of him, and freezes the moment—on film. The image registers both the banality of capture and perhaps the attempt by a photographer to push the other way.

The LCD frame shares several features with the camera’s viewfinder, particularly the display of representation in real-time. But the rear-facing frame has an unmistakable resemblance to the familiar, rectangular borders enclosing what had counted as western art for centuries (i.e., that which was worthy of framing). The molded, raised plastic on the back of the camera forms a physical border, a tactile frame that cues us toward what it is that we should shoot. The framing convention of the past is now resurrected on the back of today’s common camera.

This repeated ‘shooting-and-looking’ at the ephemeral, frozen image is a two-step process that first addresses the photographic subject, and then immediately investigates the LCD frame for evidence of the photographer’s success. The photographer is now the viewer, and the viewer, the photographer. And because of the whiplash caused by chimping, the photographer now participates in a rash, malformed process—a process more interested in the ownership, or capture, of the camera’s subject than a meaningful study of another within his community.

Chimping, and the technology that enables this practice, strips away a photographer’s ritual of the past: an emerging likeness that magically appears under the red darkroom light bathed in chemically-diluted water (courtesy of Rochester). And this is not simply nostalgia. Nor is it a concession that the older craft is a better craft. Rather, the various technologies of photography can cause us to rethink, more thoughtfully, the ways in which the photographer participates in a measured exchange with not just friends and family, but also strangers we might get to know through the act of photographing. We need not cover up our LCD screens with gaffer’s tape (as some have apparently done), but we can ask how technology leads us to look in certain ways, ways that resist contemplation and limit relationships. And we might consider how to use the same technology to see each other anew rather than as objects to be consumed.

Perhaps, we should celebrate a different kind of ubiquity–the prospect of affordable technology for the purposes of capturing loved ones, strangers, and the details of everyday life. And significantly, as argued here, we should celebrate that the shared viewing of a small LCD screen to show off images to others, enacts and instigates a sense of community. The larger point is this: accessibility need not be at odds with a reconsideration of our photographic practice. Such rethinking can work toward the democratization of attentive, measured ways of photographing each other—looking at each other—for amateurs, enthusiasts, and professionals alike.

Photograph by Elliott Erwitt/Magnum

Daniel Kim is a former photojournalist and recently completed his first year of Ph.D. study in rhetoric in the Department of Communication, University of Colorado. He can be reached at daniel.h.kim@colorado.edu.

0 Comments