By guest correspondent Emily Dianne Cram

Two children in Afghanistan play in an alleyway between two houses. The child on the left awkwardly turns forward while looking back towards the viewer. The child, whose name is Mehran appears to be running toward a place in the distance where bodies blur almost indistinguishably from one another. Or maybe Mehran is running away from the spectator watching the scene unfold. Whether moving towards or away from particular coordinates, the important point to note is that the viewer of the photograph sees Mehran suspended in what appears to be a moment of stasis, yet simultaneously always moving.

Mehran’s story is one of several featured in a recent New York Times essay and slide show that chronicles a practice known as “bacha posh,” in which female-bodied youth pass as boys to secure their families’ status within their communities. The title of the essay—“Afghan Boys are Prized, So Girls Live the Part”—cues the spectator habits the “gender abroad” genre typically evokes: condemnation of a misogynistic practice. Yet, such a judgment seems problematic if we take another look from a perspective that troubles how we think about gender.

What is remarkable about the slide show is the banality of bacha posh in a cultural context Westerners typically see as marked by strict gender segregation. In the image, below, Azita Rafaat, a member of Parliament, leans down to address Mehran, who dresses as a boy.

The entire scene invokes the narrative of a mother attempting to quiet and contain an unruly child in public. Rafaat’s hand curls firmly around Mehran’s shoulder as she demands the child’s attention with what appears to be a stern look. Rafaat reacts with an expression that is in equal parts puzzlement and discontent. What is especially distinctive about the photograph is how Mehran’s white clothes blend into the bodies of the men in the background, while Rafaat, shrouded in black, awkwardly ushers the child through the scene. And what we get is something of an allegory for the often confusing norms of public and private behavior that implicate the equally confusing norms of gender and sexual identity as they manifest in their local contexts. And in the end, Mehran’s particular identity hangs in the balance.

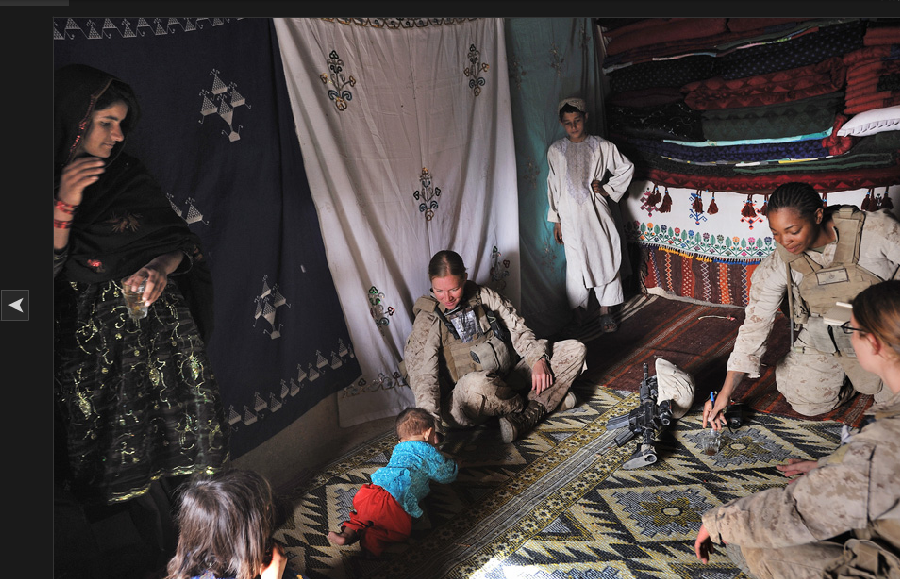

These photographs illustrate how gender in particular is a way of moving one’s way through the world to produce forms of social relationality. Yet, this view is contingent on seeing gender as a permeable category that people use as a means of building their communities. Accordingly, gender is an embodied act, something that is done to produce a relation to others in the world. This perspective enables us to see gender in transition, and how cultural practices often exceed the strict binaries of male/female and woman/man. Perhaps if we take our everyday embodied violations of categories more seriously, we can see the work gender does in a different light, rather than rush to judgments about others.

And yet, the act of seeing gender in transition is imbued with its own paradoxes. In the photograph below Zahra, a girl who has passed as a boy since childhood, gazes pensively through sheer curtains towards a bright, sunlit day.

The juxtaposition between the shadows behind Zahra’s back and the white light greeting “hir”* face and torso suggests that the secret past is coming to an end. Part of bacha posh is a transition into womanhood and the rites of marriage and motherhood. For Zahra and others, such a transition is difficult and at times undesirable because of the way their bodies sediment a particular way of being with others. Another look shows Zahra gazing towards an inevitable future with a sense of heavy dread, and we learn not only of hir desire to live as a boy, but that s/he has never “felt like a girl.”

Zahra’s story shows the contingency of gender, and the heartbreak that emerges when one’s own desires for a particular embodiment conflict with community norms and practices. This tension is endemic to the human condition, one that we all embody as we attempt to find the way our bodies fit into spaces of the world.

* “Hir” is a neutral pronoun that serves as one alternative to the gender binaries embedded in the English language. I choose to use “hir” in this case because of the way Zahra describes hir embodiment: female bodied, yet desiring a male public presentation. “Hir” emerges from a transgender critique of language, a perspective that understands the limits of and inventional potential of language in articulating the complexity of embodiment.

Photo Credit: Adam Ferguson/NYT

Emily Dianne Cram is a PhD student in Rhetoric and Public Culture at Indiana University, and her research engages the intersections of visual culture, embodiment, and gender and sexuality. She can be contacted at emcram@indiana.edu.

3 Comments