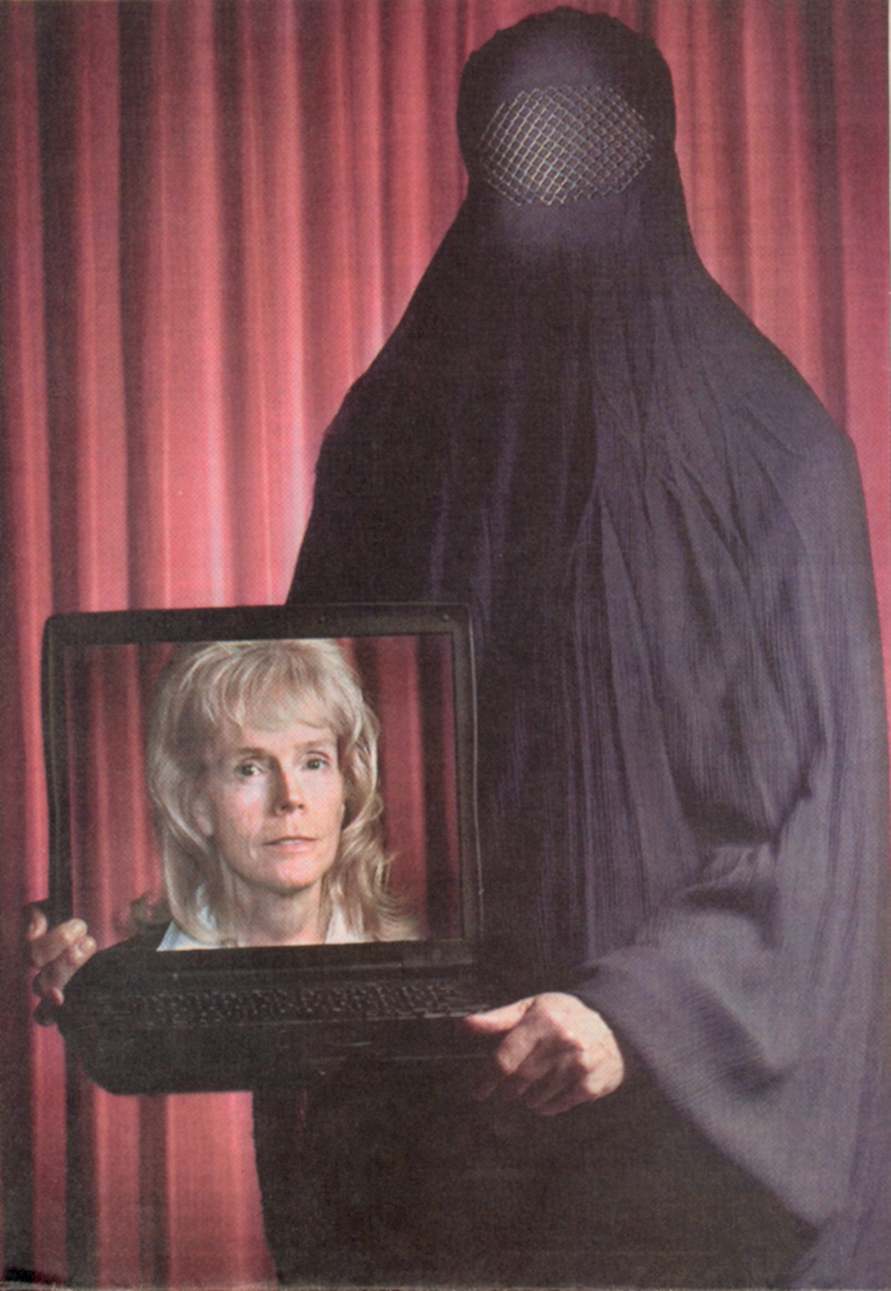

This photograph took up almost a full half-page above the fold for a recent report in the Weekend Arts section of the New York Times:

The caption says, “The New Museum of Contemporary Art Onlookers inspect the lobby and the facade of this seven-story structure on the Lower East Side, which opens tomorrow.”

And so they do. But why are we being shown the onlookers and not the building that they find so interesting? The photograph itself would not seem to be the reason as it is hardly a study in dramatic intensity. The viewer’s gaze is directed every which way, whether cued by the many different sight lines of the onlookers or by the way the view expands unevenly but consistently outward across the rear of the frame. The division of the horizontal axis by the posts into uneven thirds further breaks up the scene. The image becomes a triptych, but one that doesn’t tell a story and has only accidental coherence.

It is a remarkable picture, nonetheless, one that could hang on the wall of the museum. The photographer has captured what usually is only a blur in the background of our consciousness but now can be seen in pristine clarity. And what is seen? Society. Modern, urban, liberal-democratic society. Not all of it, of course: what we see is young, hip, affluent, cultured. But that’s easy to see. The street scene is defined not by those attributes so much as by habits of civic interaction that are much more broadly distributed in the developed world today. Look, for example, at the spacings between the individuals and the several groupings of people. The proxemic ratios there will be maintained whenever possible in public in the US.

Let me focus today on how this photograph exposes one dimension of the complex social experience on display. I’ve written before about how public life depends on visual norms, habits, and practices, and how critical theory can misrecognize these forms as long as it depends on assumptions that visual media are largely instruments of power by which elites create spectacles to manipulate the masses. By contrast, one can point out that even social critique calls for “transparency,” a visual metaphor that if nothing else assumes that someone is looking; more important, social phenomena are constantly changing, and social theory needs to do the same if it is to account for public culture as that is something different from manufactured consent. Today’s photograph provides one example of what one might look for if taking seriously the idea that modern civil society requires or at least makes use of forms of seeing.

Let’s simply catalog the many ways the sight is marked in this photograph. The caption features an art museum–an institution devoted solely to public viewing of visual artworks. The people in the photograph are identified as “onlookers”–defined by the act of looking. They may also be citizens, or New Yorkers, or connoisseurs of the arts, but all that is folded into “onlookers.” And looking on is a specific type of seeing: one is not within the scene being observed, not part of the action, but rather seeing “from the sidewalk” as it were. They are spectators, but not degraded by that. In fact, they are “inspecting” the building; although not inspectors, they are engaged in an inherently visual act that includes an assessment, in this case, an aesthetic judgment. That is what the architect assumes, and so we are seeing the other side of architecture: not the building, but the culture within which it makes more or less sense. The building will be judged according to how well it meets the visual challenge carried by the story caption, “New Look for the New Museum.”

And those are merely the captions. In the image itself we see people defined by looking, which clearly goes in many different directions probably reflecting different points of view. Even the dog is looking. More specific looking also is evident, from someone pointing to direct others’ view, to the woman pointing her camera, to the couple in the background who have to watch for traffic. The city is a place to look, from streets to signage to buildings. It also is a place to look at people: those in the picture are posed by the still image as if for inspection. The red coat in the right middle fixes that element of the scene, which is carried across the image by the common fashion of blue jeans, casual coats, shoes, headgear, bags, and postures. Like the woman in red, albeit to varying degrees, everyone has agreed to not only see but be seen. No burqas here.

This shared visual experience is given a reflective touch by the large windows (a transparent barrier) and the reflections off the polished floor. We see, but always through things (even the air can distort) or off of things (such a this web page). One reason people go to art museums is to become more intelligent about how they use their eyes, and the photograph is doing some of this work for those, like the onlookers in the photo, not yet inside.

The final touch is provided by the sign in the center rear of the composition: “City Sights NY.” This cheap sign for what I assume is a low-grade tourist operation is perfect here. On the one hand, it is the art museum’s opposite: a commercial, artistically worthless painting for pre-packaged “sight-seeing” for bumpkins. No wonder it is getting exactly zero attention from both those interested in the museum. On the other hand, it is just the other side of the same street: the city is a place for seeing, and people go there for that reason. The vulgar, vernacular signage tells us why the museum is there, for both are all about “City Sights NY.” And that is a story about not only New York but also anywhere people are to mingle together in modern civil society.

To see what I mean, just look at the picture.

Photograph by Suzanne DeChilo/New York Times.

6 Comments