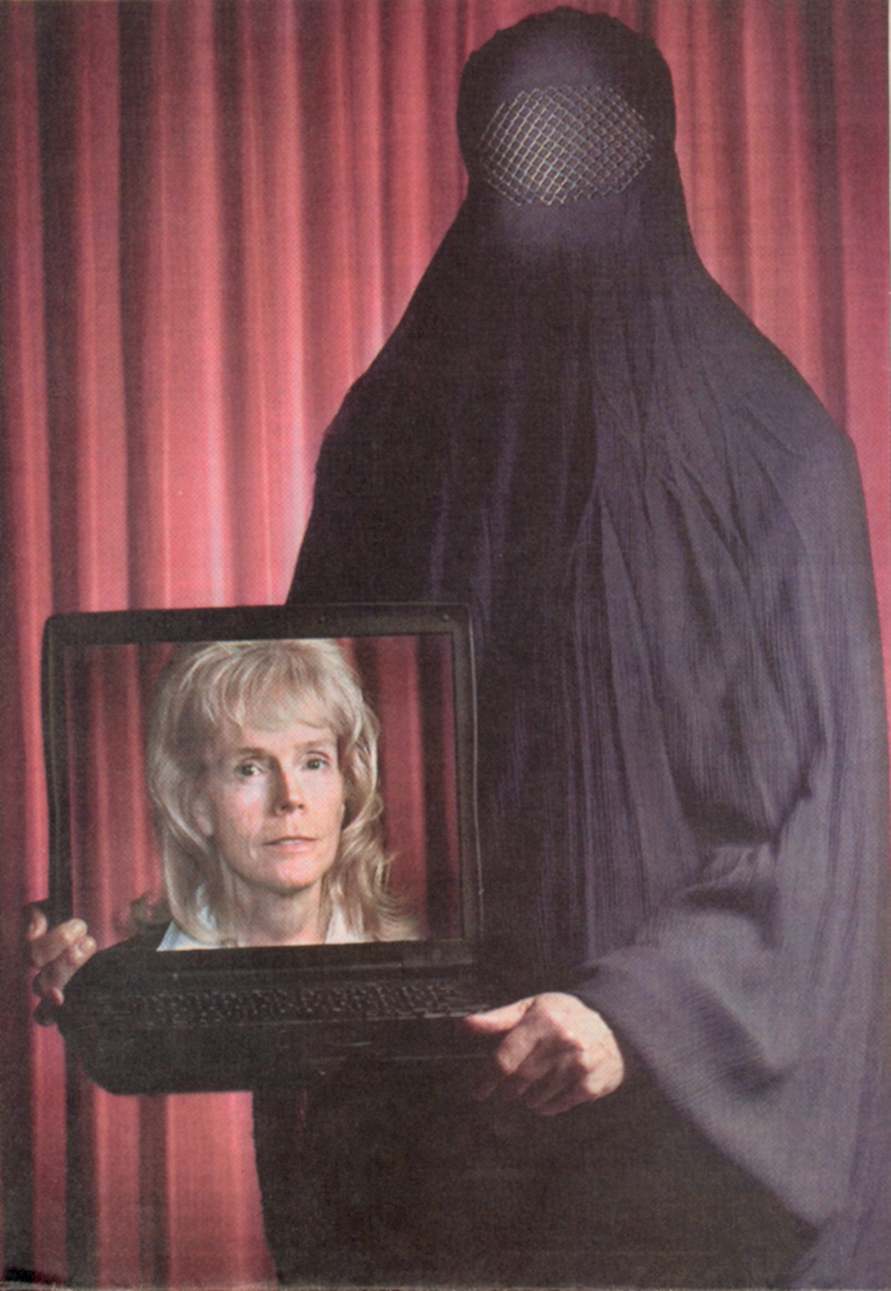

This is the third post in what is becoming a series on how the burqa challenges the visual norms that define public spaces in the West. (Previous posts are here and here.) Today’s image is a small work of public art that I’ve held on to for several years:

You are looking at Rosemarie Skaine, author of The Women of Afghanistan Under the Taliban. Or are you? She is under the veil, while you are shown her hands holding a laptop whose screen reproduces a digital image of her face. She is both there and not there, and so the photograph creates an eerie strangeness. (Georg Simmel observed that the stranger “is near and far at the same time.”)

Or the tableau can be understood to include two women, one imprisoned under the veil by premodern authority and the other enjoying full personhood due to Western scientific achievement. It also implies a narrative of progress: women who are completely effaced by traditional customs such as the burqa can be liberated by Western technology to achieve self-realization. In any case, the tableau is striking precisely because it intensifies, almost to the breaking point, two assumptions defining the visual public sphere of modern liberal societies: liberty involves the ability not to hide but rather to be seen, and the face is the essential medium of individuality.

Although Skaine’s entire body is in the room, it is the digital image of her face that is the sole marker of her identity. That face, however, is an image; unlike the women behind the mask, it cannot see, and it can be reproduced indefinitely or eliminated by touching a key. The irony is that Western woman’s face lives in the modern technology but acquires a greater vulnerability for that fact. So there are two women there after all: one is premodern, devoid of personality, and looming large, monstrous, like an image of death itself. The other is modern, the epitome of individual personality, but also disembodied and mechanized. Perhaps both are under the veil. If we can assume that continued global modernization will liberate women now in burqas, the fate of women in the West nonetheless becomes less clear. One hopes for a third alternative, which is one indication that the artist has done her job.

There is a lot more that could be said about his tableau, and there are other images that I’d like to put alongside it. But that will have to wait for another day. The photo was taken (posed) for a story in an Iowa newspaper promoting the book’s pending release in 2002. Photo by Harry Baumert for the Des Moines Register, October 14, 2001, E-1.

The image is indeed both eerie and strange, and a wonderful addition to the blog’s growing theme on burqas. I see another two possiblities for reading the image as a trope:

1) Paul de Man talks about prosopopeia linking face to the giving of subjectivity to (an)Other (“Autobiography as Defacement.” In The Rhetoric of Romanticism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1984). His face is no longer the surface of an intact self, but the figuration that is imposed by someone else. When I am spoken into being, it is as though the Other were painting my face in language. Having experienced the painting of “my” face, I inscribe and internalize a sense of personal identity. For de Man, in other words, the figure grants the referent; the referent does not precede the figure, nor does it determine it. Because the process by which a mask, a face, is superimposed on a voice is linguistic, it is continuously defigures and refigures itself.

This reading speaks to the tension between seeing Skaine’s face and not seeing it. The burqa-clad woman is ripe for prosopopeia; the other Skaine who makes eye contact with the viewer refuses to the “faced.” Her stare is already a subject.

2) The image may simply be drawing attention to two different but equally oppressive cultural systems. Perhaps the woman “in the laptop” is trapped just like the one in the burqa. In now full-fledged burqa debate, some Western women are asking what the difference is between being forced to cover up and being “forced” to discipline your body in other ways: wear shoes that damage your feet, starve yourself to be the right dress size, etc. Granted, the lap top photograph isn’t about clothing, but the trope of containment seems to recur in both the burqa and the frame around the tiny face on the screen.

(By way of introduction: thanks for a good blog. I have been a lurking reader for a while and look forward to the posts!)