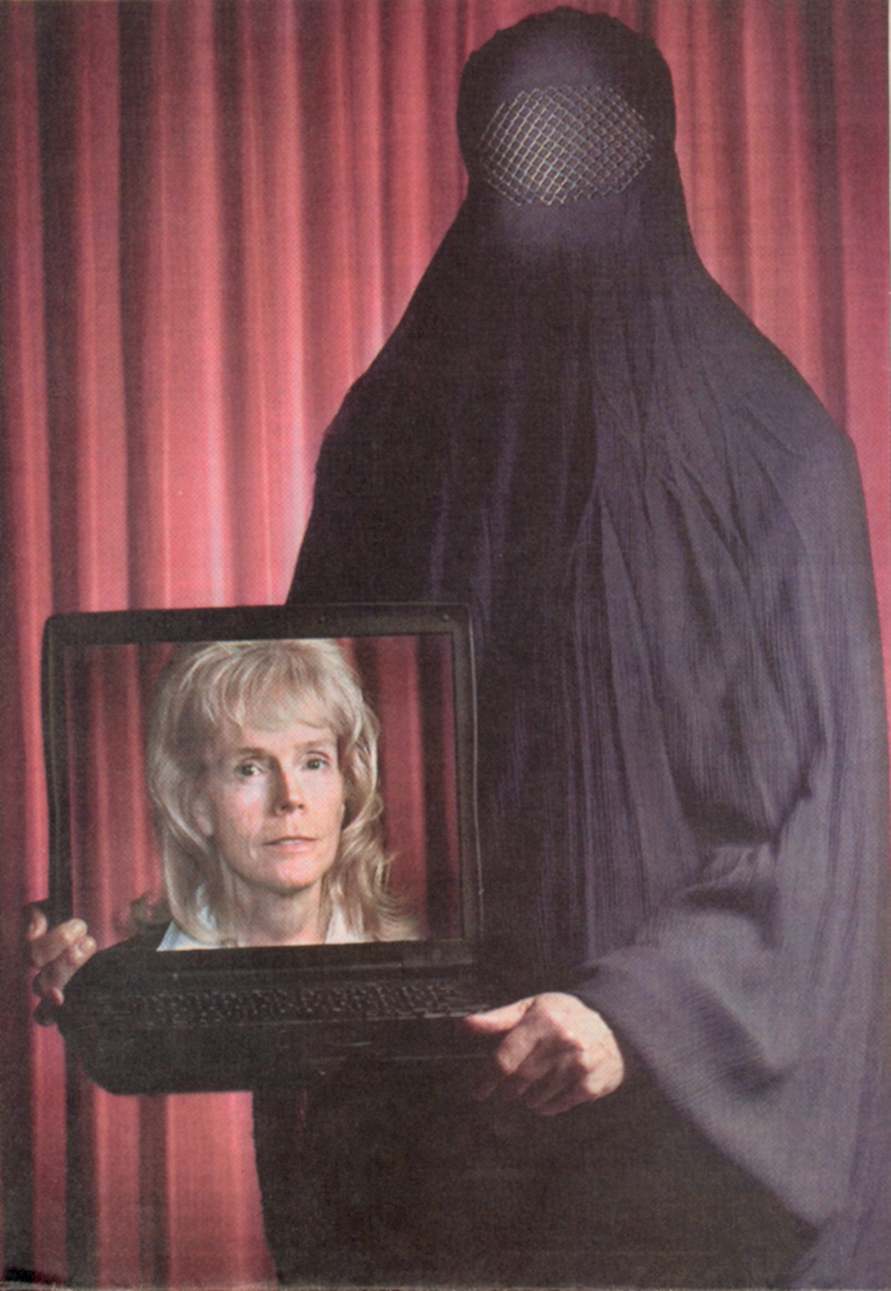

Robert and I have spent much of the past ten years trying to figure out what makes a photograph “iconic.” We have some pretty good ideas about what leads to photographic iconicity, but all but one are arguable: Unseen photographs never become iconic. And the condition of see-ability, of course, is that the photograph actually has to be taken. And now the truly great city of New York, in all of its infinite wisdom, wants to regulate the taking of photographs, requiring permits and $1 million dollars in liability insurance from anyone who “wants to use a camera in a public place for more than 30 minutes” or from “a group of five or more people who plan to use a tripod in a public location for more than 10 minutes, including the time it takes to set up the equipment.”

The NYT reports that the policy is not “intended to apply to tourists or amateur filmmakers or photographers” who, the rules emphasize, are “rarely” effected by the proposed regulations. We are quite sure that this is of very little comfort to citizens who might actually want to picture the world around them. The permits are “free” (though liability insurance, one might imagine, is a different matter), and the proposed rules include all sorts of exceptions (designed, no doubt, to navigate and manage First Amendment concerns), but Kafka taught us about the bureaucratic style and we all know about the slippery slope of regulation. And the question has to be, exactly what interests are being served by such regulations?

The advocacy group Picture New York has an on-line petition and is planning other protest activities, as in the picture above of photographers with faux-cameras. Thanks to Ted Striphas for calling my attention to this issue.

Photo Credits: Gabriele Stabile/New York Times