Guest post by Aric Mayer

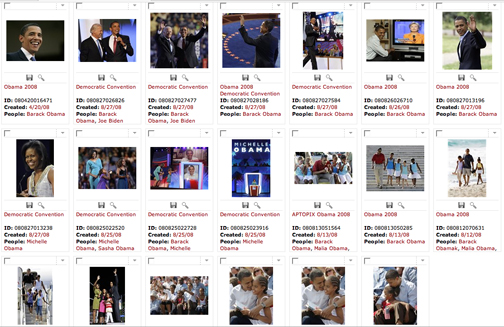

A page on the AP photo website, where a search for “Obama” yields 20,652 publishable images, or 1,033 pages just like this one.

A former colleague of mine is a photo editor at a weekly magazine. In the normal course of her job she edits a section that requires her to review up to 18,000 images a week to publish fewer than 20. Most of this editing takes place over the course of two days. As she goes through these images that are coming in off of the open wire, she knows that her competitors are looking at the same images as well. If she misses one great image that is picked up by another magazine, there is going to be some answering to do. Talk about pressure. There is a kind of marathon quality to the performance. I’m not even sure the human brain has evolved yet to handle this much volume in visual stimuli.

The technical way that almost all photo editing gets done these days is through editing programs that allow hundreds and thousands of images to be searched for by keywords and then browsed through as thumbnails. See something you like, double click on it and you get the full size preview. And here is the limiting factor. Almost any image going through this system must have some appeal as a thumbnail or it is almost sure to be overlooked. In other words, if your image doesn’t look good at one or two inches on a computer screen, it isn’t likely to make it through the editing process at all.

Due to the volume that editors are handling under tight deadlines, this is a necessary evolution. It also is a great limiting factor on the kind of work that gets published. Loud, colorful, graphically dramatic work tends to win the day. Quieter, more complex work has a tough time competing on this level because it doesn’t work at that size and in that format. We can look to another related medium, painting, to see more clearly how this works.

An early lesson that a beginning painter must learn is that scale and format really do matter. Before a painting begins, the shape and size of the surface have to be determined, and those decisions will influence the effect of the painting right through to its completion. The next lesson is that painting a larger painting is not at all like making a small painting. Increasing scale changes everything.

On the larger scale, detail at the surface level is the same only there is a lot more of it, and to make an integrated piece the detail must be related to the entire piece. Which is to say that making an 8 foot by 10 foot painting requires approximately 144 times the attention to detail than an 8 inch by 10 inch painting, since the larger painting has that much more surface area.

But, making the larger painting is not like making 144 of the smaller ones, because the entire surface must come together to make a whole. All the ingredients, including the scale, must be necessary for it to work.

What does this mean for photography? Making a bigger photograph is very different than making a smaller one. Scale matters, but the ingredients in the photograph must require that scale in order for it to be necessary. There must be sufficient detail, resolution, and interest in the photograph to hold up at scale. Since venues for larger images are shrinking while smaller images get into distribution easily on the web, the aesthetic of the thumbnail is winning the day.

Consider also the tonality of the image. Printing photographs on paper is a master craft, as is making color separations for CMYK printing in magazines. In each case, the final viewing experience is largely under the control of the printer. Not so on the web.

A few years ago I went to the opening of a gallery show exhibiting some recent photojournalism. Many of the images were familiar from their appearance in popular magazines. What was surprising to me was that the images, printed at 30×40 inches, in many cases appeared to have less impact at that size than they did at full page and double truck sizes in the magazines. On the wall they started to fall apart. The scale wasn’t necessary for the final object.

Years of working in 8.5×11 or 11×17 as maximum scale had made those photographers maximally effective in that format. With one notable exception–all work shot with a Leica on black and white negative. The grain just got sexier as it went up in size. The compositions were tight and the teeth of the film carried through. Digital images blown up past their prime need real help to make it. They tend to lose surface appeal.

The web is one of the easiest ways to distribute photography and it is one of most limiting ways to view it. Almost all of the problems I have detailed above play out over the web. Images have to be small to be viewed properly. There is significantly less detail in most computer monitors than there is in a finely made print. Each step of the way something is thrown out. By the time the image reaches you on the other end of this computer exchange, it is but a shadow of its real self– the final, beautiful, nearly perfect print.

There’s an historical corollary to this in the music biz, when ablum artwork shrank from the glorious 12-3/4″ square format of vinyl LPs down to 4 3/4″ square format of the CD. Covers of albums that were originally released during the vinyl age don’t look nearly as good (and sometimes don’t make sense) when shrunk down to CD size.

In one case I know of an artist produced an vinyl album during the transitional phase. The album was called Martin Simpson/Leaves of Life. When the CD came a short time later, the word “of” was no longer distinguishable between the other two words of the title, so it read as though the title were “Martin Simpson Leaves Life” (which he hadn’t).

So a google image slideshow option. You hit the button and the full size images flash by, with a user-adjustable rate of flow.

Yes, very good point about the need to appeal at thumbnail size. I’ve thought about this with respect to the popular photo-sharing site Flickr. Most sharing is done at that size, then if people find a photo appealing in miniature then they may click on it, they may comment, they may mark the piece as a favorite. The latter actions result in gaining popularity and eventually making it to the top 500 for any given day. But if a photo doesn’t appeal at that level, regardless of quality otherwise, it will likely suffer in number of viewers.

All good observations.

And to take your argument a step further, Eszter, once a photo achieves popularity on Flickr, it has passed a vetting system that gives it value based on the popularity of the crowd. It is a frequent and valuable experience for all photographers who wish to create an individual voice to have a mentoring process that generally occurs, at least at the start, in private, where one has the chance to experiment and grow with the constructive and sometimes hard to hear criticism of someone whom you respect and who is much further along in their creative process.

More can be accomplished in an hour of being in a room with a mentor and a box of your prints than the crowd can likely ever provide. To find an individual voice requires a time away from the group, where one can individuate to a degree and then return with a new sense of vision. If success is based on immediate crowd appeal, the measures of quality become more and more based on broader common denominators, and cohesive but perhaps contrary visions are penalized because they do not achieve that appeal. There was a hilarious and insightful experiment on Flickr where someone anonymously uploaded a classic Cartier-Bresson image and it was dismissed as being amateur and deeply flawed. Perhaps most telling was that the reviewers didn’t recognize one of the signature works of one of the modern masters of photography.