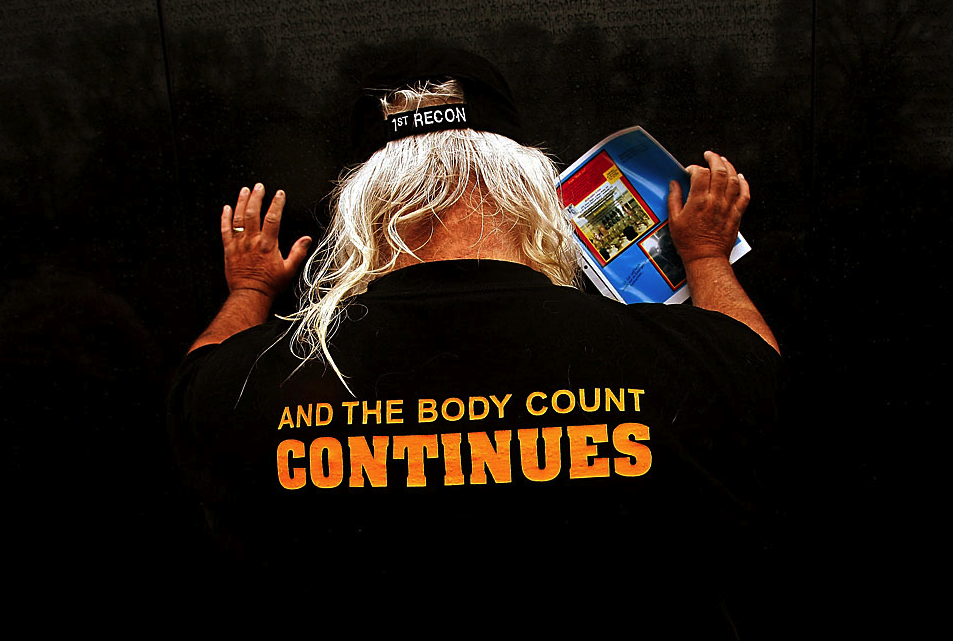

Violence in Iraq is slowly rising again as US troops are being moved to Afghanistan, but many of the photographs being published continue the narrative of successful pacification that has been keeping the war off the front page for months. Against that backdrop, this photo struck me as all too evocative of the continuing violence in the Middle East.

The New York Times caption read, “A blood-stained bed at the hospital in the Kadhimiya district of Baghdad after two suicide bombings on Friday.” The fine-grained detail in the caption–right down to “the Kadhimiya district,” should you want to put another pin on the map–contrasts with the refusal of intelligibility in the image itself. We see only an ugly smear, not the precise details of injury or death. Only the bloody aftermath, not even the event itself. Whatever drama played out in this ER, it’s over. Only the stain remains.

Perhaps because it looks like an inkblot from a Rorshach test, the drying blood invites the viewer to make sense of what is there. But what is there doesn’t make sense. Instead of meaning, narrative, purpose, or resolution, we are confronted with the inchoate. Instead of a body, only the bloody trace; instead of presence, absence; instead of the peace and repose of clean sheets and healing, only more of war’s bloodletting, waste, and loss.

Of course, even meaninglessness is a form of meaning, and stains invite further reflection. Sin is understood metaphorically as a stain in some cultures and one rather pertinent religious tradition, as Shakespeare knew when writing Macbeth. It is easy to imagine how the war in Iraq has stained America, and how the stain of war will persist there long after it has been forgotten by people elsewhere. Such thoughts are a legitimate use of imagery, as is true of the deeply metaphoric nature of language itself. But they also can carry one too far into the realm of thought and so of abstraction. It is more fitting sometimes to simply stare at the image and let it enter your soul–as a stain, a bloody stain.

Photograph by Christoph Bangert/New York Times.

American casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan are reported at icasualities.org. Civilian deaths in Iraq are reported at Iraq Body Count. Civilian deaths in Afghanistan are reported here.