One thing that nearly everyone on the political spectrum seems to agree about is that the U.S. immigration bureaucracy is an incredible mess. Of course, there is no consensus on what the problems are, let alone the solutions, but there truly doesn’t seem to be anyone who thinks that the status quo is acceptable. I suppose that’s a start, but if we are going to make any real progress we need to come to some agreement over key terms, and there, of course, is the rub, for at the heart of the issue of immigration policy is a disagreement over terms: is the problem a matter of “undocumented immigrants” or “illegal aliens”?

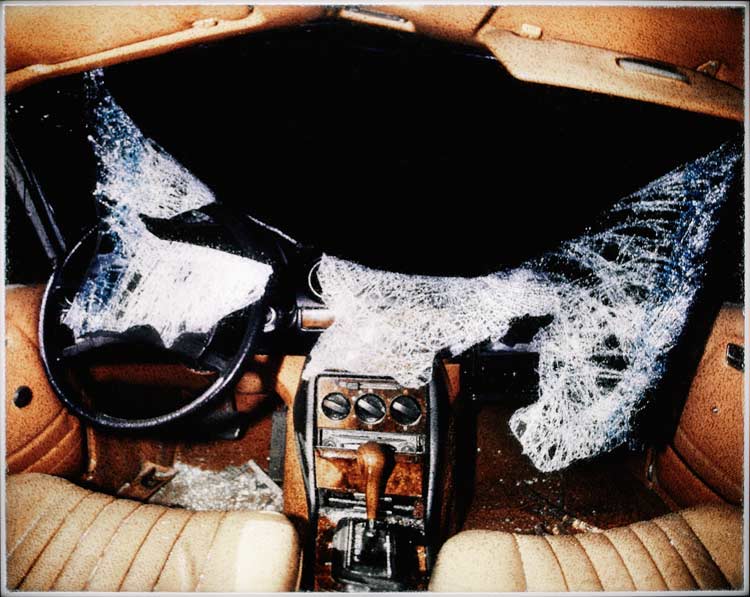

I was led to think about this problem this past week when I came across a photo-essay in the Chicago Tribune on “Flight Repatriate,” one of a fleet of Boeing 737s contracted by US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to “expedite the removal” of “illegal immigrants” to their “homeland,” often in Central or South America, but also Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Since October 2007 ICE Air has transported more than 367,000 immigrants to their countries of origin (a 77% increase in the number of deportations since 2006), the vast majority of whom have lived peaceful and law abiding lives within the US borders, notwithstanding their designation as “illegal.” Animated by a desire for “cost effectiveness and safety,” Air ICE flights include “sandwiches, cheese and crackers, fruit, bottled water, civilian clothing, checked baggage and a private nurse.” As one ICE official put it, “there is no reason why we can’t treat them with as much respect as is possible.” Indeed, “nonviolent” passengers can even have their shackles and handcuffs removed on international flights. It is hard to imagine how anyone could complain. And yet …

From the moment of its origins the U.S. has been a land of immigrants, and across the broad expanse of that history the vast majority of those immigrants—starting with the pilgrims and moving forward—have been “undocumented.” The development of the modern nation-state changed all of that, of course, but not even a bureaucratic sensibility can mitigate the irony of castigating “undocumented immigrants” as “illegal aliens.” The doubled shift in terms is much to the point, as the absence of documentation becomes not just a sign of exclusivity, i.e., non-citizenship, but of criminality, just as one’s status as an immigrant becomes a sign of alterity that warrants a stigmatizing alienation further marked by the presumed need for armed guards, caged busses, and shackles and handcuffs.

Some undocumented immigrants might be criminals (rather like, say, some Wall Street bankers and financiers can be criminals) or even dangerous individuals, but it is somewhat churlish to designate and treat them as such simply because they lack the proper documentation—or at least one might imagine that a democratic society would adopt a more liberal and humane attitude towards such persons.

But then again, perhaps one can’t be too careful. After all, in the right hands even a three inch heel can be a deadly, dangerous weapon.

Photo Credits: Alex Garcia/Chicago Tribune