Sometimes there are no words, nor need there be. When I came across this image, I was instantly no longer reading a newspaper. A moment before, I had been habitually scanning for information, considering arguments, making judgments, and otherwise getting orientated for the day. And then I was in another place entirely: a place of suffering and consolation, and of both mortality and the possibility of something eternal.

I had entered a featureless room of earth tones and shadows, as if the anteroom to the underworld, only to see two sides of the human condition: one terribly exposed, and the other disturbingly dark. It seems an intensely personal moment and yet profoundly universal. One looks in vain for some way to reduce the terror lurking in the image, to learn enough so that it can be placed back into a sense of order, movement, resolution. But no face can be seen, and the light illuminating his body is absorbed completely by her black cowl.

The news was still there to be had by way of the caption: “A woman took care of a wounded relative on Saturday inside a mosque being used as a hospital by demonstrators against the government in the Yemeni capital.” The accompanying report added more. But I hadn’t seen merely a woman or a wounded relative. I had seen man’s naked, vulnerable flesh and his throat exposed as if for the slaughter. And I had seen a figure veiled in black holding the victim firmly, almost possessively, as if there were nothing else that could be done. And, of course, I had seen a pieta, the classic image in Christian iconography of Mary, the mother of Jesus, holding his broken body after it has been taken down from the cross.

The pieta is more Roman Catholic than Protestant, but though not Catholic I had no trouble seeing that artistic form as it is part of my cultural heritage. Whatever the unknown photographer may have intended, the comparison is there to be made and to motivate a powerful emotional and ethical response to the image. But should it matter that the two people in the photograph are almost certainly Muslim? Although Islam defines itself as the heir of Judaism and Christianity, the artistic traditions could not be farther apart at this point, for the suggestion that we might be looking at the image of god would be blasphemous. Worse yet, another reason the image is so powerful is that the black, hooded figure can also be seen as an angel of death claiming another soul. This demonic vision not only must be far from the truth of the scene, but also sits well with deep-set prejudice.

Thus, the dilemma: On the one hand, seeing the two figures through the cultural lens of the pieta may frame response in a manner that is profoundly appropriate. Doing so provides intense identification across cultural barriers to reach universal truths of human experience. On the other hand, transposing their experience into another culture’s symbolism can seriously distort the actual relationship of those in the photograph, while also suggesting a false universality on Christian terms precisely when one ought to be laying down such presumptions about how well people can understand one another on sight.

Thus, we need to see through symbols, but in both senses of the verb: to use them to see more than we might see otherwise, and to recognize and look past their limitations to see what they would distort or occlude. Nor is this double vision limited to matters theological.

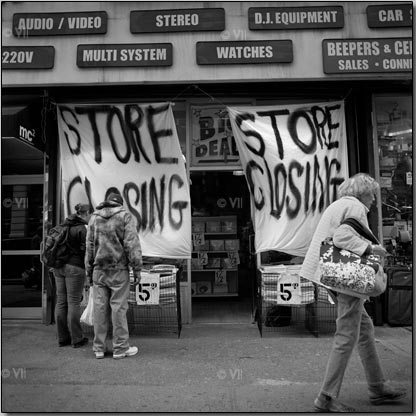

“Libyan fighters regrouped Tuesday during the siege of Surt.” (The story is here.) Uh huh, and irregular troops taking a cigarette break is news? Once again, we are being taken somewhere else, to a place where a death’s head and the peace symbol are part of the same identity. Once again, darkness and light work together to feature two dimensions of human experience; if less complementary in principle, they are eased together by the global consumer economy. Culture in the digital age is all about mash ups, but this also could be a study in either irony or illegibility. You tell me.

Photographs by Samuel Aranda and Mauricio Lima for The New York Times.

7 Comments