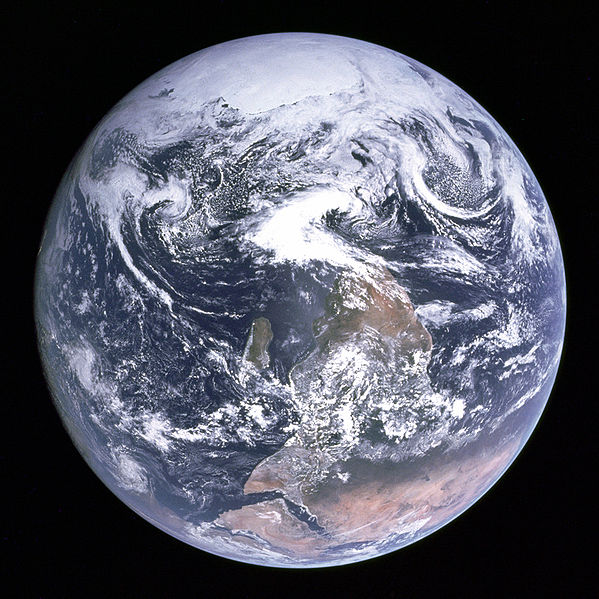

It’s a fine thing to know thyself, I’m told. If only that were as easy to do as it is to say. One of the ironies of the modern era is that the incredible achievements of science and technology have led primarily to knowledge of the natural world–even to the distant edges of the universe and the beginning of time. There has not been a corresponding increase in the ability to know what it is to be human, to be a society, or to be an individual person–indeed, those goals have become ever more complicated by the advances that have occurred in the natural and human sciences. Recent developments in imaging technologies provide intriguing demonstrations of how the production of knowledge can bring us both closer to and farther away from knowledge of who we are.

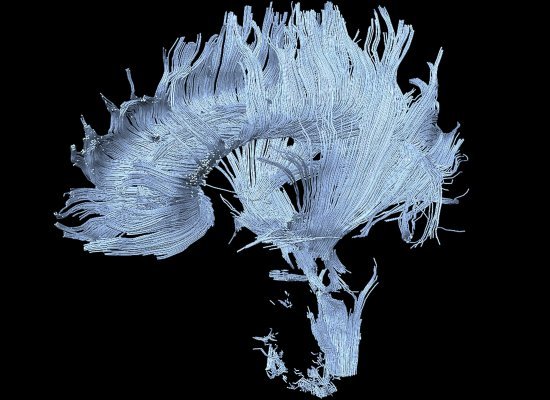

This stunning image presents axion pathways in a live human brain. It seems to impart immediately an aesthetic knowledge of human consciousness, and reflexively so: I see an essential dimension of neural organization, and my brain looks at another version of itself. The beauty of the vibrantly interwoven blue tracery against the black background suggests complexity and density, while its visual analogies with hair, helmut, crest, and other natural and artistic forms carries the image, like consciousness itself, across the divide between inside and outside, seen and unseen, self and world.

But aesthetic knowledge alone goes only so far, at least in this domain. Does this image impart anything else to those not studying axion pathways? Does it extend the horizons of self-knowledge to include a more articulate sense of our inner world, or does it create an illusion of self-knowledge and of scientific mastery of what remains almost completely unknown? Consider these additional options as well: perhaps it constructs a model of human being that will lead inquiry down one path but not another–toward, say, reductive knowledge of bodily functioning rather than understanding emergent properties in complex systems. Or it might offer not merely knowledge but possibility, that is, an ability to visualize complexity in a manner that might lead to productive analogies and genuine insights regarding how human beings are creatures with a remarkable capacity (though not the only one) for transferring information across networks.

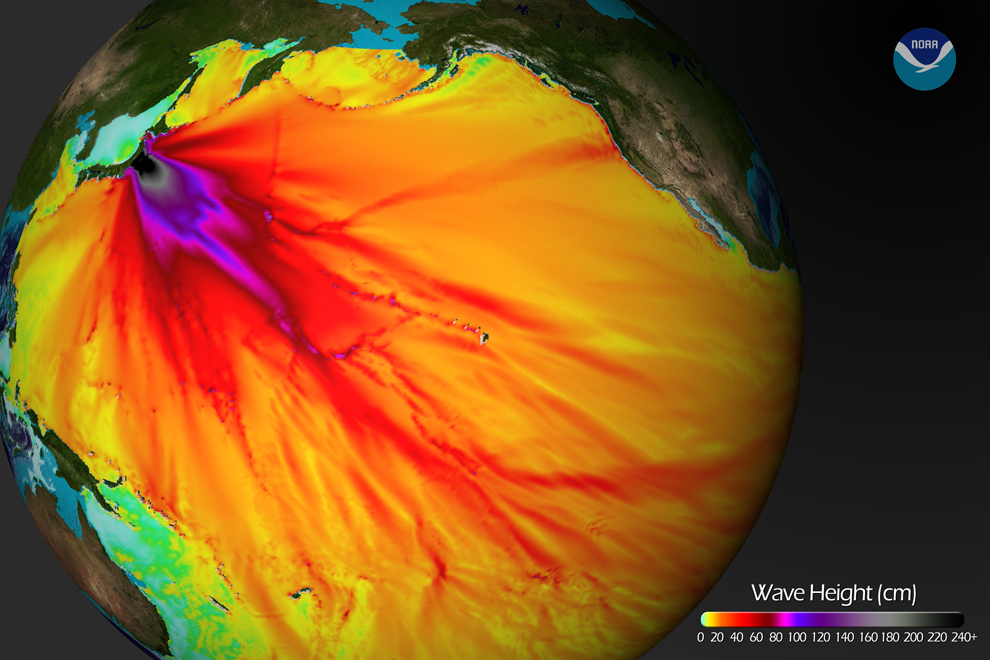

Networks like this one, for example. It could be a circuit board, but it is the city of Milan, Italy. The radiant energies are palpable yet not threatening, perhaps because of the broad distribution throughout the system. Though a vast fabrication of streets and buildings on an electric grid, it seems almost organic, as if a life form that had grown through cellular replication in close adaptation with its physical environment. There is a decorative beauty to the array, which articulates both nodal intensities and patterned expansion. Frankly, it looks smart: as if intelligence had emerged through the growth of complexity.

As so we know ourselves a bit better, perhaps, for seeing these images, but imperfectly so. For example, the self-awareness activated by the first image is in fact flawed: the brain belongs to a stroke victim, and, happily, your brain stem probably looks quite different than the one above. Likewise, the experience of the city on the ground will usually have little relationship to what is seen here, not least when encountering any of the problems sure to be a part of life on the street.

Both of these images provide an opportunity for thinking anew precisely because they are the result of extraordinary instrumentation: we cannot otherwise see into the brain or from the vantage of the International Space Station. They can be misleading for the same reason. Even so, I think these and others like them present a marvelous opportunity to better understand the human species, modern societies, and perhaps even how you or I are embedded in complex systems that each are partial analogues of the others.

MRI by Henning U. Voss and Nicholas D. Schiff; and ISS/NASA.