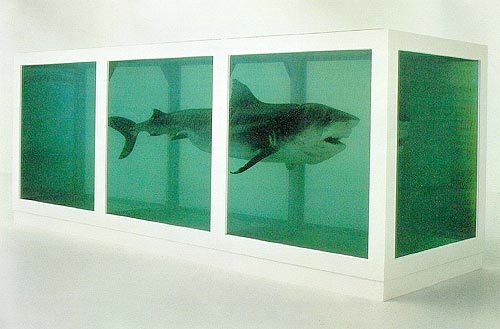

I’m about to get sentimental about a small photo. Small in several senses: the copy I have is smaller than what we usually post, the photo depicts only a few birds on a tiny spot of land, and neither they nor their image is likely to change much of anything. In fact, this is an image of incapacity, even futility.

Even the viewer is made to feel a bit inept, as you have to lean forward and peer into the photo to see what is happening. The dingy colors of fading snow stained with–what? urine?–and the dim water offer little contrast in the dull light to the black and white uniformity of the birds. There seems to be no focus, no action, no drama, and certainly nothing like the grandeur of nature with its magnificent, triumphant struggle for existence, as typically portrayed in TV documentaries.

So what is happening? The caption at the New York Times story coupled with the photo said “Adélie penguins struggle to save eggs submerged by snowmelt.” It seems that climate change is producing particularly distinctive effects in the polar regions, and one consequence is that this penguin colony is having its reproductive cycle disrupted while also suffering greater exposure to predation. Sudden adaptation is difficult in a harsh environment, and the prospects for the species are not good.

At this point, one might expect conservatives to jump in and save the penguins. After all, the March of the Penguins, a documentary movie set in Antarctica, became a hit because of its supposed demonstration that monogamy, heterosexual parenting, loyalty, and other traditional virtues were natural law. As with all such allegories, the facts were another story, as penguins are about as monogamous as our own species, which is nothing to crow about. In any case, the point never was to care about the penguins themselves, and no one is likely to now.

But I’m going to get sentimental anyway. What is happening is that the snow has melted under some of the penguins’ eggs, and because they are trapped in the water they can’t be incubated. The water will be warmer than the snow but not warm enough, while washing away any heat that could be supplied by the parent. The eggs will die. And the birds seem to know it.

One could say that these are but a few eggs, and that the species will adapt as the birds that place their eggs on better snow will reproduce while the others don’t. Nature is a harsh teacher, but one can learn, right? Wrong, actually, if that is your theory of evolution, but that’s another discussion. What grabs me is that the birds want to adapt to the change and can’t. They are congregated around the eggs as if trying to figure out how to solve the problem, and they are trying to do what they can that situation: roll the eggs out of the water. That is what any engineer might do, if the engineer lacked arms and tools. The penguins are doing everything they can do to save those eggs, and that means that they care about the eggs and, as their efforts are failing, understand that a disaster is slowly befalling their little community.

Obviously, the sentimentality here is not mine alone: witness the word “struggle” in the caption. But is it misplaced? I don’t think so, because once again the story really isn’t about the birds. I happen to believe they are capable of emotional intelligence and rational problem solving, albeit while severely limited in their manipulative capability on land. That is beside the point, however. What the sentimental response does is open the viewer to understanding what the photograph is really about. That is, to see why it is not such a small thing after all.

The pathos of the photograph is that the penguins are standing amidst a slowly unfolding catastrophe but handicapped as they try to deal with it. That deficiency is due to biological limitations, including their lack of hands. Just as important, however, is that they are only dimly capable of comprehending the full extent of the danger, and lack the cognitive, social, and political resources needed to adapt successfully. They care about their young, but caring is not enough. To avoid what is fast becoming their fate, they would need to analyze the terrain, organize and deliberate about the options, and adjust their habits for sustainability. They aren’t wired to do that, of course. Those are human capabilities, right?

Long story short, we may be like the penguins after all.

Photograph by Fen Montaigne, as part of Fraser’s Penguins: A Journey to the Future in Antarctica.