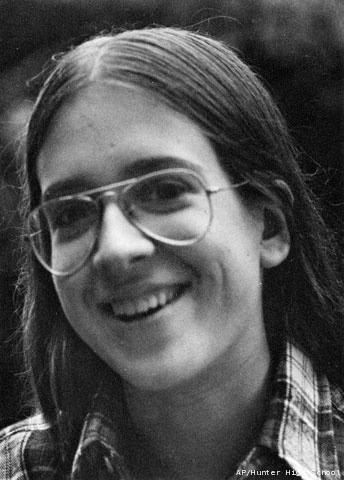

This photograph from Kabul, Afghanistan could have been captioned “Return of the Body Snatchers.”

Gallows humor is pretty cheap, but it may be as sane a response as any other to another suicide bombing. The attack last week killed 18 people, wounded at least 47 others, and generally made a mess of things in the center of the capital. And somebody has to clean up. I could be snide and say “Your tax dollars at work,” but the US occupation of the country is one reason the bombings occur, and US troops are as logical a choice as any for the clean-up detail. Even so, there is something unnerving about this image.

The caption said that the body was being loaded onto a truck, but it also looks as if it is being loaded into a shredder. Or worse, some mobile rendering vat–everything processed, nothing wasted. One neatly wrapped body is being conveyed up and into the machine, while another lies on a gurney waiting its turn to be fed into the industrial maw. In fact, they will be transported and unloaded while respectfully wrapped against additional harm, but nonetheless one senses that something awful has been revealed. Something about how life and death alike are being captured by the routinized violence of military occupation.

Whatever the motives of the suicide bomber and whatever the intentions of the clean-up crew, this photograph has captured the anonymity, repetitiveness, and pointlessness of 21st century warfare. Death and destruction are spreading like global plagues–as I write this, ethnic violence has erupted again in Kyrgyzstan–and entire societies are transformed into that strange late-modern hybrid of new technologies and demolished infrastructure. In rubble world, you can see cell phones and twisted rebar, digital cameras and gashed streets. And in place of thriving marketplaces, we see soldiers and other state functionaries going about the business of restoring the city, not to what it was before the blast, but to what remains after the worst of the damage has been carted away.

This dual character of being both modern and degraded is evident in the photographs themselves. The photo above depicts both an efficient funereal detail and the degradation of seeing bodies being treated like they were being recycled. It documents a modern military machine–not only the truck itself, but the entire military organization that so effectively manages violence and chaos–and also the waste and wreckage spread by war. And the image itself is a marvel of digital reproduction that will become lost among many other images much like it, each another fragment in the growing detritus of seemingly endless conflict.

One way or another, violence in the 21st century is a story of modern technology strangely implicated in the production of ruins. So it is that photographs of the machinery of death are both factual and allegorical. The facts are tied to the present; the allegory extends into the future.

Photograph by Ahmad Masood/Reuters.

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes.