Discussion of a recent post raised an important question about visual thinking. In commenting on a murder suspect’s strategic manipulation of press coverage, I concluded that he still looked guilty.

Of course, I wouldn’t convict on that, and an astute reader noted that “the appearance of ‘innocence’ can only be another act,” and so it seems that there is no point whatsoever to looking for either guilt or innocence in how a person appears in public. And that’s before considering the role of racial, ethnic, and other forms of social bias in perception.

The focus of the earlier post was on the use of appearances rather than their accuracy. But what about their accuracy? I think most people would agree that you shouldn’t judge guilt or innocence on the basis of how a person looks. When that happens–and it does happen–the results include both false convictions and a free pass for con artists. But if that is true, why do we think we can see character?

And we do think we can see character. Scientists report that infants already are paying close attention to facial cues. People are constantly and often accurately discerning that others are in this or that mood. As we get to know people, we sometimes can read much deeper elements of personality on the basis of a glance. Photographs are used the same way, not least to communicate emotions. John and I have been reading social experience, attitudes, and ideas off of photographs for five months now and we rarely are called on this point. As long as the photographs are dealing with known individuals such as Bush, representative figures such as the latest casualty in Iraq, stock social types such as students, or common experiences such as shopping, there is little to be worried about. Whether right or wrong about the individual in the frame, the image provides a basis for conversation about those things that define collective life. And the court of public opinion is not a court of law.

All of this is a long introduction to another photograph:

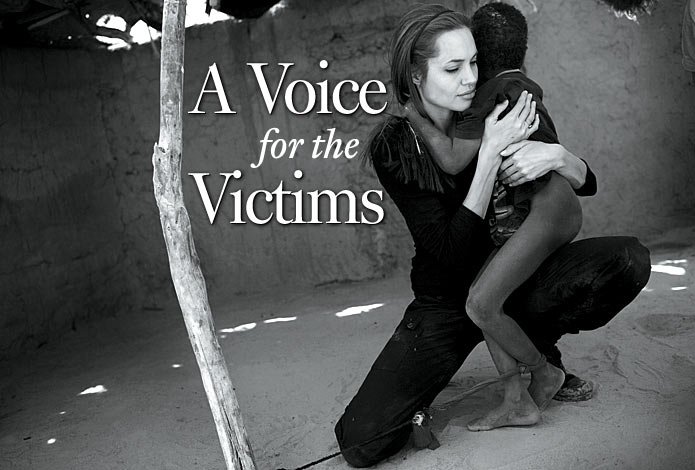

You are looking at Pakistan’s President General Pervez Musharraf reviewing an honor guard with his hand-picked successor, Gen. Ashfaq Kayani. There was this little problem of being a “President General”; fortunately, that term still embarrasses Musharraf’s patron, the US. So Musharraf has turned over direct control of the military, the better to maintain US support for his dictatorship. The transition involved a series of rituals, including a tearful speech. The tears may have been heartfelt; again, that is not the important question.

I’ll cut to the chase: I think we can see character here, and these guys are thugs. If that is too harsh, how about “hardened autocrats.” Of course, they will look otherwise in family photos, just as they will have behaved otherwise when playing with their kids. They may not be thugs all the time: just when in power or maneuvering to stay in power. So what? Any dictator can have a good side. The question is what side will be in charge when power is at stake. I think we can see the answer in this photograph. Musharraf may be a dedicated warrior against Islamic fanaticism, but he is no more a democrat than is Gen. Kayani.

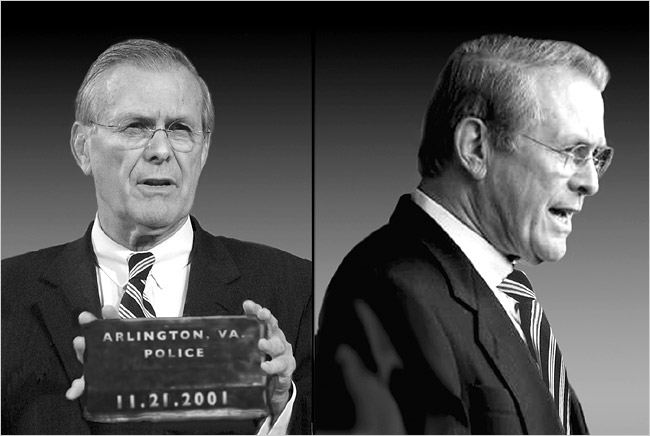

And now for the quiz. What do you see in this photo: the appearance of innocence, or the character of an autocrat?

Perhaps the question should be, if we can see character, why can’t we see guilt? One answer is that guilt is an assessment of past conduct involving a violation of a law, and these things are not to be seen in the present. There also is the complication of distinguishing between legal and psychological guilt, not least because some people need not hide guilt because they don’t feel it, while others can feel guilty for crimes they never committed. But perhaps there is another answer: the guilt is there to be seen, were we but able to see it. I would never convict on such evidence, but I can’t help but think that there is more to be seen than we realize, and that seeing it might get us closer to justice.

Photographs by Anjum Naveed/Associated Press; Digg screen grab of the You Tube video of Musharaff’s interview on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart.