The Costa Concordia is a floating resort. Larger than the Titanic by nearly seventy feet, it boasts 1,500 cabins, one third of which have private balconies, the world’s largest fitness center at sea (65,000 square feet), five restaurants (two of which require reservations), thirteen bars (in addition to cigar and cognac bars), a three level theater, a casino, a discotheque, a Grand Prix race simulator, an internet café, and much, much more. It houses 4,300 passengers and an additional 1,100 crew members—that’s one crew member for every four passengers—on seventeen decks. It is valued at just less than $600 million dollars. And while we would probably not consider it a technological marvel in the late modern world, as we would have considered the Titanic or the Hindenburg in an earlier era, it is nevertheless something of a marvel, its sheer magnitude making it larger than life.

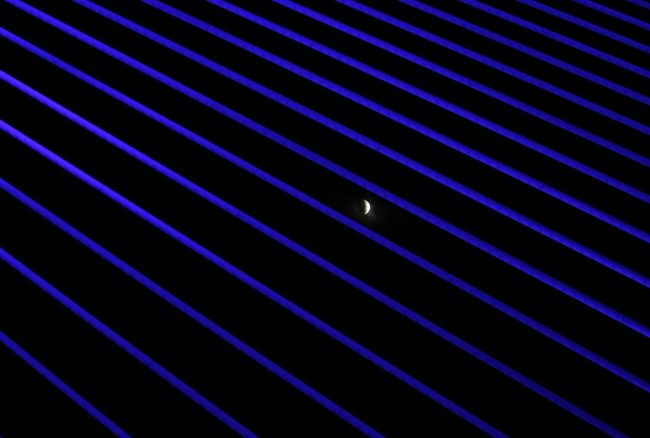

Of course, the photograph above doesn’t quite do it justice. Foundered on a rock off of the coast of Tuscany near the island of Giglio that left a 160 foot gash in its hull and listing to the starboard side, the marvel and magnitude of the Costa Concordia are somewhat diminished. The actual cause of the grounding has yet to be finally decided, though there is no evidence of bad weather or other emergency conditions that would have required bringing the ship this close to the coast line.

It is both a catastrophe and a tragedy. As of this writing the death toll rests at eleven with twenty or so others still unaccounted for. And as with the mythological Icarus, the disaster is a result of sheer hubris. In the days ahead the focus will no doubt be on the captain’s unauthorized deviation from the planned course and his lack of good sense animated by assumptions of unfounded pride in either his skills as a sailor or in the capacity of the ship. Or perhaps we will learn that he was intoxicated or otherwise distracted. We are already hearing that much of the problem was due to the fact that passengers failed to participate in muster drills, as if the disaster was their fault. In any case, “human error” will no doubt bear the weight of the burden. And to be fair, a good measure of this may well be warranted. But of course the hubris here extends beyond the human failings of the captain or the passengers and extends to a society that places its unfettered faith in its technological ability to master nature.

Elsewhere we refer to this faith as “modernity’s gamble”—the wager that the potential for catastrophic risks assumed by a technology-intensive society will be avoided by continuing progress. Modernity’s gamble is most apparent in the building of airplanes and rockets designed to conquer the skies, or in nuclear power plants intended to free us from our reliance on fossil fuels, but it is no less relevant to things such as online banking and commerce, where the risk to economic catastrophe is no less disastrous—or likely. It may be that we are passed the point that we can refuse modernity’s gamble, but surely we need to learn to respect it and to avoid challenging the odds for frivolous purposes. That here the wager was lost in a disaster involving a technologically advanced and sophisticated playground for the upper classes only underscores the hubris of a society that cares little for how it employs its resources and even less for how it respects its environment.

The photograph above is telling in this regard, as it contrasts the failure of an overextended and idealized technological mastery of nature (for fun and profit!) with the sustainable houses and buildings that occupy the coastline. A storm could come along that wipes out the village, no doubt, but it wasn’t an unpredictable weather event that led to the disaster here. It was the failure to respect modernity’s gamble. And while those who built the village appear to have respected the natural crag of the outcropping, preserving it as a defense against the sea and the wind, but not trying to overcome it, those sailing the Concordia did not respect it, running aground in the process. As Don Quixote’s sidekick Pancho reminds him, “whether the stone hits the bottle or the bottle hits the stone … its always bad for the bottle.” And so here, the ship once visually magnificent, is humbled; indeed, in its own way it appears to have settled into a fetal position of total resignation. It is perhaps a subtle irony that the ship’s name—referring to the state or condition of agreement or harmony—is betrayed by the scene depicted in the photograph in which harmony rests with the village and not with the trappings of an unbounded hubris.

Photo Credit: Remo Casilli/Reuters.

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes.

0 Comments