Homosexuality occurs across the rainbow of human cultures. The same seems to be true of homophobia, except that the numbers are much larger. Why are so many people troubled by this small constant in human variability? There will be many sound answers accounting for a range of social structures and personality types, but sometimes an image comes along that reveals a deeper truth.

The real “threat” of gay life has nothing to do with sex, natural or otherwise. The real problem is that it exposes just how much human nature is a contrivance–something that itself is not natural as other species are natural, but rather excessively given over to artifice, performance, and an often painful interplay of social display and self-consciousness.

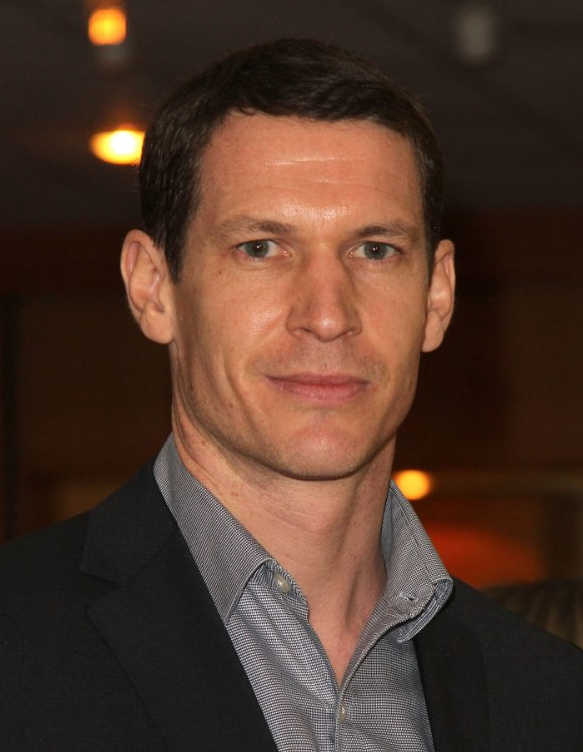

And that’s why I love this photograph of two guys of a certain age at a gay pride parade in Bogota. I assume they are wearing nurses’ hats, but I’m not going to speculate on that, although they should get some credit for the matching lipstick. Gender trouble (alerting us to the fact that sexuality is performed rather than given), queering the standard categories otherwise in place with business suits and hospital uniforms, whatever might be the carnivalesque disruption of social categories underway here is only half of the story. (An important half, as our management of the surface of things has enormous consequences in determining whether people will thrive or suffer, but not the point I want to dwell on today.) The drama in this photo is all about the face.

Let’s spell it out: are they wearing masks? They could be. Especially the one on the right, as the smile looks somewhat frozen, as if sculpted in plastic. And the headscarves could be hiding the rest of the trappings, whether Velcro straps or a loose fit at the back of the head. But why the double mimicry of both age and a feminine profession–what kid would do that? And the one on the left wears his face too well: the meaty heft to it, the tight creases of control between the eyes, and the delicious lift of the upper lip as if on the verge of a sneer–well, you can’t buy that.

The “naturalness” of the face is heightened by the way the black eyeglasses are perched awkwardly high up on the bridge of that considerable nose. The rather large lenses seem small on that face, as if there only for vision but not really very good for that. It starts to dawn that the make-up doesn’t extend only to the red lips and scarves, or to the silver ornament and the purple straps and the garish rose tint from the umbrella.

They are wearing masks–their faces. Eyes look out from behind those facial masks just as they also look out from behind a pair of glasses. Those faces, which almost could double as the conventional tragedy and comedy masks signifying the theater, suggest that these two individuals are old troupers in the play of life. They have used their masks to fend off trouble, make their way in the world, express their thoughts and feelings, please, deceive, warn, and love. Those faces carry scars and the knowledge gained, they are studied for intentions and more, and at last they will dissolve to black and become mere vessels emptied of consciousness.

Wonderful things, but in the end still masks. And that’s the problem. Human beings yearn to forget that they are creatures of their own making. Too much responsibility, and not enough assurance. Better, it seems, even for society to be ruled by nature, hardly a merciful sovereign, than to see it as a stage where one’s inner and outer selves will never line up exactly.

The gay pride parade may be a celebration of human rights, but it also is a reminder that everyone is queer. That’s one more reason why we should be thankful there now are so many parades, and that everyone can attend.

Photograph by William Fernando Martinez/Associated Press; one of many in a slide show at The Big Picture on gay pride parades around the world.

0 Comments