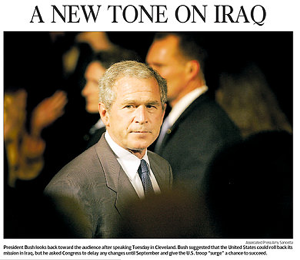

Several days ago I commented on the common and ordinary conventions of photographic representation that tend to guide and discipline photojournalistic decorum in representing the President of the United States. As I noted there, the conventions typically employed reinforce our perception of the president’s power and presence as commander-in-chief. But I also noted how the conventions can be managed in ways that call attention to their artifice, thus undermining the window-on-the world sensibility that they generally promote. And sometimes, I suggested, they can be actively exploited so as to produce effects that are wholly contrary to our ordinary expectations. In recent times such conventions have operated in something of a tension between efforts to minimize and maximize representations of President Bush’s stature. Two photographs of President Bush speaking in the Rose Garden on July 20th make the point—and more—exceedingly well.The first photograph was used to lead an AP wire report with the headline, “Bush Criticizes Democrats on Iraq”:

The AP, of course, is required to be “fair and balanced” in its reporting of any event, and no less so a media event planned by the White House. But this photograph tells a somewhat different story than the headline. First, it is important to note that in its published version the photograph is smaller by at least half than the version I’ve reprinted above, and this is not inconsequential to the interpretation it invites from its viewers. Shot from a low angle, as per the convention for emphasizing the power of the president, it is also shot from the side and at long distance. Indeed, the president is miniscule, once again dwarfed by the scene in which he is performing his office. Indeed, he is so small in relationship to his surroundings that it is hard to know exactly what he is doing—one has to strain to recognize that he is standing at a podium. He is backed up by an entourage, but they are almost entirely obscured by the roses, which clearly dominate the scene. And note too how the use of the roses to frame the action situates the viewer – presumably the American people: It is as if those who are viewing this scene are interlopers, voyeurs jealously sneaking a peek at a party to which they have not been invited. And the color seems off too, slightly washed out in a way that suggests that the roses have begun to pass their prime; the visual effect carries over to the president’s jacket, making it seem more like a drab and faded grey, than blue, his shirt and tie barely visible. It is hardly the image that an embattled president seeking public support for a contentious policy would want to portray.

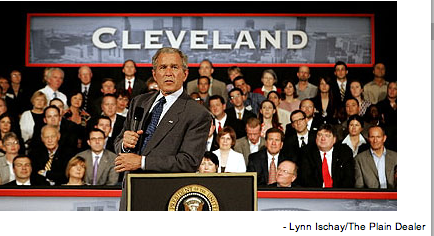

One might expect to find a very different photograph of the event at the White House website and so they might be surprised to find this image which, at first glance, seems to be akin to the one used by the AP:

The differences between the two photographs are subtle but invite very different affective responses. Note first, that at the White House website the image is slightly larger than the one reproduced here. In this image the president is shot in middle-distance, and as such his body stands in comfortable proportion to the scene in which he acts. He dominates the frame and appears to be in full command of the event unfolding: Standing at a podium, speaking to an unseen audience, he is the master of his house/garden. His entourage of supporters are visible and prominent, albeit subordinate; dutifully at attention and attending to his words, they reinforce the sense that he is in control. Equally prominent is the U.S. flag, somewhat obscured in the AP photograph. But most important are the roses, which now function as a natural and pleasant setting rather than as subterfuge or camouflage. They neither obscure the viewer’s line of sight nor hide the viewer’s presence from detection. While still to the side, the viewer is now a legitimate part of the scene. The colors are rich, saturated, alive, the roses in full bloom, the suit a bright and pleasing blue, his white shirt and red tie clearly connecting him to the flag that sits behind him.

Much more could be said about these photographs, but the point to underscore here is that each displays a very different social order: One a dim and dying world animated by secrecy and political jealousies; the other a bright and vibrant world, alive to the future and animated by the presumption of political openness and equanimity. The impulse here, no doubt, is to ask: Which, if either, is the real world? Or is it a third version that one finds at the NYT and that seems to sit somewhere between the two? But such questions are dangerously myopic, if for no other reason than the assumption that one photograph is fundamentally more real than the other. Every photograph is a construction, a tool for making (and unmaking) the world that draws upon complex mediating technologies, recognizable conventions of representation and cultural practice, and the inventional skills of photographers and editors. The better questions to ask are how do visual technologies enable the imagination and production of alternate worlds? What do such images reveal—both about the worlds they portray and about us? And what do they (necessarily) hide or obscure? And, perhaps most important, what are the implications of such constructions for the world (or worlds) in which we want to live?Photo Credits: Gerald Herbert/AP Photo, Joyce N. Boghosian/White House Photo