Commentators on photography frequently claim that the image is a counterfeit of reality. Beware the image, we’re told, as it is not the real thing. But it you look at what people do with images, you can see far more than people being mislead. What I find particularly notable is how ordinary people are enlisting images as foot soldiers in public demonstrations. Instead of displacing reality, images are being used to increase the scale and impact of democratic advocacy.

You could see it as Chinese parents held photographs of children killed when their schools collapsed during an earthquake, and you can see it now as Iranians protest their government’s attempt to fix the presidential election.

Here a protester is not only marching in the street but displaying a photo of another protester who was shot by a government thug in an earlier demonstration. For an example using an earlier photo of state violence, look at the bottom of this post, and see others in photograph 9 at The Big Picture. That’s only part of the repertoire, however.

I doubt anyone thinks this guy actually is Mir Moussavi, so the protectors of reality can stand down for a moment. He is doing something much more significant than imitation, anyway: by making the photograph a mask for this political theater, he puts the political leader’s face on the body politic that is the multitude of people in the street. The leader, who actually is living on the edge of house arrest, is given the force of the people, whose identification with his cause and their right to a fair election is given specific statement.

There may be more going on as well. This carnivalesque mashup may also be a response to the State’s attempt to mobilize the same means of persuasion on behalf of their theocratic regime, as they do here:

These women are holding photos in a demonstration on behalf of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The stock portrait of Leaders with the Flag and corresponding production values are in sharp contrast to the dynamic documentary witness in the first image above. If you want to communicate Order and Stability instead of change, however, this state-sponsored image will do.

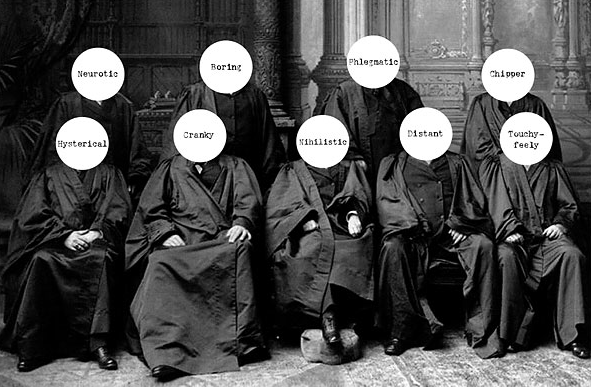

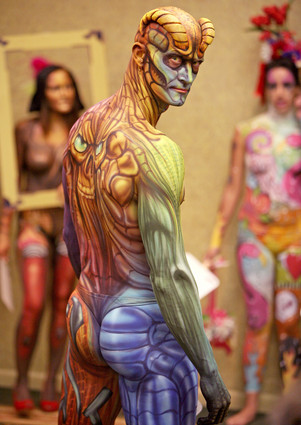

It’s tempting to leave it at that: a contest between competing images that reflects the two sides of the polarized confrontation in the street. The disenfranchised people, their candidate, and a dynamic visual culture on one side, and traditionalist social orders, clerical leaders, and propaganda on the other. But I want to tip the scales further on behalf of democratic public art, which, after all, should be too brash and ungainly to be easily categorized. For that and other reasons as well, you really ought to get a look at this:

The photographs are from the slide show at the Huffington Post. Photographs 1-3 are Getty images; I don’t have an ID on 4.