Click Above to See James Nachtwey’s TED Prize presentation.

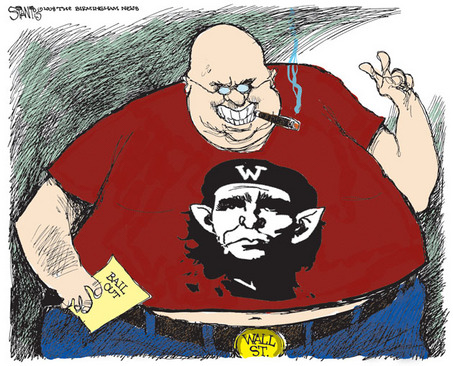

Sight Gag: The Free Markets Survive

Or for an alternate take, click on the cartoon.

Credit: Scott Stantis, Birmingham News

“Sight Gags” is our weekly nod to the ironic and carnivalesque in a vibrant democratic public culture. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course, we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.

Underground Democracy

Guest post by Aric Mayer.

New York City is one of the greatest cities of the world, and certainly is one of the most integrated and diverse. Here you can find all cultures and all ethnicities practicing their own heritages side by side. People who in their homelands are at war with one another here manage to find ways to coexist. This coexistence is exhibited best in New York City’s Subway.

When the train doors close, instance and ephemeral communities are formed. Status and power do not buy you a seat at rush hour. On an average weekday five million riders board the train, and whether rumbling along in the darkness of the tunnels or the daylight above, community standards are created and enforced by proximity.

In an age of internet associations across geographic lines, it is becoming easier and easier for communities to form, communicate, share ideas and reinforce each other’s belief systems. The internet has the promise of a great Athenian experiment in civic discourse. Unfortunately the trend seems to be that people are increasingly able to seek out and congregate only with others who are like them, and diversity, once the great possibility of the internet and the fundamental promise of democracy, suffers, replaced by a stultifying homogeneity.

And yet, by contrast, the New York City Subway is the great leveler of class, ethnicity, and virtually any other form of difference and distinction. It encourages the daily practice of tolerance and cohabitation among millions of users. And by doing so it has become a gritty sort of civic square where all, for a time, are mostly equal.

Many pictures of democracy in action will be offered over the next weeks as we lead up to one of the most important presidential elections in recent memory. And many of these will be grand visions of power and triumph. In the midst of this, let us not forget what a great jumble of people we are. And democracy is a messy business, worked out in the daily act of differing peoples coming together to work out their differences — or just to live with them.

Stay Tuned For Something Big

Photojournalist James Nachtwey was one of the 2007 recipients of the TED Prize. TED stands for Technology, Entertainment, Design and it brings people from these three worlds together to spread ideas, mostly by challenging fascinating thinkers to “give the talk of their lives in 18 minutes. These talks are available on-line at TED.com. The annual prize winners are given a $100,000 award AND granted one WISH to help change the world. James Nachtwey’s wish is to “break [a story that the world needs to know about] in a way that provides spectacular proof of the power of news photography in the digitial age.” That story will break on October 3 both on-line and around the world. Don’t miss it!

James Nachtwey’s Homepage

The Organic City or the Global Desert?

Will the 21st century be a chronicle of cities or deserts? The stark contrast may seem artificial, but powerful forces are pushing global development in both directions at once. On the one hand, many hundreds of cities are growing rapidly and many of those are thriving. They are the sites of tremendous concentrations of wealth, human capital, social energy, information, and innovation. In the US, cities such as New York and Chicago are experiencing record levels of young people living in the urban core, which historically is a vital source of commercial and cultural progress. If rising energy prices keep that generation from migrating to the suburbs, then the transformation of the urban environment will continue. The future, then, will look like this:

I love this photograph of London at night. The city is a living thing, pulsing with vital forces, growing relentlessly along natural paths. The lighted arterials flow like roots feeding a plant, like blood vessels coursing through the body, like water cutting through rocks to become the channels of a great river carving the landscape. That landscape is suffused with both energy and density–an incredible concentration of social organization and electricity. This achievement is marked by the bridge and the river in the upper right of the photograph. The coordination of human enterprise and natural constraint is there in miniature, an historical token whose small scale and simplicity underscores the enormous amplification of social, political, economic, and technological power characterizing modernity.

So why talk about the desert? Because all that electrical power has to come from somewhere, and the enormous changes wrought by modernization in China, India, and elsewhere are–like the industrialized nations before them–rapidly depleting all natural resources, not least those that are non-renewable. Urbanization has been aligned with global warming and greater inequities in wealth, education, and many other social goods. To put it bluntly, one way to make a city (and a civilization) is to turn the surrounding area into a desert.

As nations compete for ever more limited resources to achieve the benefits of modern civilization, one outcome could be a lot more of this:

This beautiful image is from the Sossusvlei Dunes in Namibia. The caption in the New York Times describes the country as one of “stark beauty and riveting contradictions.” If you want riveting contradictions, you don’t have to go to Namibia, and the picture has more in common with London as well. Note how the desert trees have the same ancient natural form as seen in the aerial view of the world city. The reversal of the color fields emphasizes their similarity: the branching pattern is gold on dark in the city, and dark on gold in the desert. In place of the teeming life of the city, however, here we see an environment defined by scarcity. And in place of density, we find stability gained by resisting erosion.

Deserts, like cities, are the result of both human and natural forces. London is the sum total of millions upon millions of decisions yet still subject to the deep interdependencies shaping the planet. Deserts will grow or shrink depending on how humans are or are not able to cooperate with each other regarding resource consumption, economic regulation, and other requirements for a sustainable modern civilization. Taken together, these two photographs remind us of one more thing: just as natural beauty is evident in both the city and the desert, nature couldn’t care less whether humanity brings itself to success or failure.

Photographs by Jason Hawkes/The Big Picture and Evelyn Hockstein/New York Times. For more of Jason Hawkes‘ stunning photographs of London, go to this post at The Big Picture. The Times story on traveling in Namibia is here.

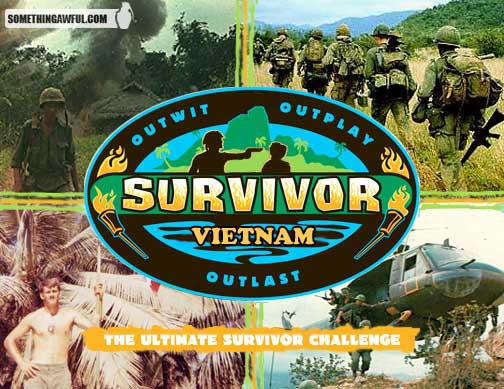

Sight Gag: Survivor – An All New Season

Credit: SomethingAwful.Com

“Sight Gags” is our weekly nod to the ironic and carnivalesque in a vibrant democratic public culture. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course, we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.

Paper Call: Visual Culture in War

Call for Papers

Taking Sides: The Role of Visual Culture in War, Occupation and Resistance

Radical History Review Issue #106:

The Radical History Review solicits contributions for a special issue on visual culture in war, occupation and resistance. Artists have often taken sides in ideological conflicts and in actual conflagrations. In terms of visual culture and resistance, the literature and music of the South African struggle, the murals of Belfast and Derry in Ireland and the poetry of the many Latin American movements for change are relatively well documented. Less analysis is available on the role of artists on one side or another of recent conflicts. Wars of Liberation and popular revolts such as those in Angola, Algeria, Iran and the Basque Country spring to mind. Despite the scale and impact of the Vietnam War, little knowledge is available in terms of the role of visual culture in the mass mobilizations against both the French and US occupations. Approaching five years into the occupation of Iraq and with numerous groups engaged in resistance, what form does visual culture play in demarcating opposing political positions? How have artists in colonized or oppressed nations viewed themselves and their work in terms of the largely western models that shape what is commonly defined as ‘art’ (the gallery, theater etc)? What has been the role of visual culture in support of imperialism or colonial expansion, as well as officially ‘state sanctioned’ cultural production?

The role of visual culture in conflict situations also prompts an examination of the implications of artistic ‘neutrality’. Despite current global instability many artists and cultural producers, especially in the western artistic tradition, consider their work to be apolitical or neutral. Can artistic neutrality be said to exist in conflict situations, or is culture ultimately, in the words of Edward Said, “…a battleground on which causes expose themselves to the light of day and contend with one another?” (Culture and Imperialism).

This issue of RHR is particularly interested in exploring these questions.

A partial list of topics of interest is available here.

Radical History Review solicits article proposals from scholars working in all historical periods and across all disciplines, including art history, history, anthropology, religious studies, media studies, sociology, philosophy, political science, gender, and cultural studies. Submissions are not restricted to traditional scholarly articles. We welcome short essays, documents, photo essays, art and illustrations, teaching resources, including syllabi, and reviews of books and exhibitions.

Submissions are due by November 15, 2008 and should be submitted electronically, as an attachment, to rhr@igc.org with “Issue 106 submission” in the subject line. For artwork, please send images as high-resolution digital files (each image as a separate file). For preliminary e-mail inquiries, please include “Issue 106” in the subject line. Those articles selected for publication after the peer review process will be included in issue 106 of the Radical History Review, scheduled to appear in Winter 2009.

Wall Street Blackmail or Ecological Prudence

The science section can be a pleasant diversion from the overheated controversies on the front page of the newspaper, but this week there is a connection that shouldn’t be overlooked. Let’s start with the science.

This is a portrait of three langurs, an endangered species residing in southern China. Between hunting and deforestation, they were on a steep slope toward extinction. This population was down to 96 when Chinese biologist Pan Wenshi began studying them in 1996. Today, despite continued development in the area, they number around 500.

The picture above may look like a nuclear family but actually is a mother, child, and another female. Monkeys have social organization, one might even say polity, to survive, and this population may even be experiencing socio-political evolution from patrilineal infantide to negotiated power sharing. What is equally impressive is how Dr. Pan called on human social organization to develop a more effective strategy for saving the langurs. Instead of enclaving the endanged population and focusing all his resources on them, Pan worked at improving the infrastructure for the human population surrounding them. Soon the villagers had clean water, medical services, a school, and more sustainable energy–basic infrastructual needs that required only smart designs, effective advocacy, and not a great deal of money. One result was that the forests recovered and villagers started to protect the monkeys from hunting.

So why am I telling you this? Because in the front section of the newspaper you can read all about the $700 billion bailout plan for reckless financial corporations that is being pushed by the Bush administration. That’s the same administration that refused to regulate the industry or address any of the danger signs that have been accumulating for several years. I’ll let that go, because now the key question is how to protect the economy. And that’s why we need to pay attention to Dr. Pan instead of Treasury Secretary M. Paulson Jr. and company.

The gist of the administration proposal is that we have to save the few in order to save the many. The few don’t deserve to be saved, that that’s not important; they are likely to salvage enormous personal fortunes despite financial malpractice, but that’s a separate issue; there are no obligations in place of continuing incentives for mismanagement, but this is not the time for that; the costs are excessive and are to be paid by millions of people who have done no wrong and will be harmed by the payout, but we don’t have time to do anything else; this is contrary to the reigning ideology that is one cause of the disaster, but we must be practical rather than principled or “partisan.” Or so we are told.

I’d like to think that this debacle is one of the last vestiges of the political economy of twentieth century oligarchy. That’s too optimistic, of course, but it does suggest that the complex problems of the twenty-first century require smarter, less resource-intensive, and–let’s say it–more democratic solutions. The approach taken by Dr. Pan, for example. His basic idea is that in order to save the few, you have to save the many.

There has been a lot of talk about prudence lately in respect to both Wall Street and the presidential campaign. The administration’s bailout is not prudent. In the name of saving the system it puts system sustainability at risk. While claiming that the issue is of the highest seriousness, it refuses to take the time for adequate deliberation. Instead of concentrating on foundational issues such as a fair distribution of wealth, maintaining essential infrastructure, providing adequate regulation for a modern economy, and otherwise protecting the basic social contract that undergirds the society, it ransoms all that for a quick fix.

The plan may go through. A similar propaganda campaign led to another trillion dollar disaster not too long ago, so the cynical money may be on Paulson. Whatever happens, the rest of us need to start emulating Dr. Pan’s approach. He had specific advantages that favored its development, of course: he was far from the center of power, had little money, and cared about more than his own self-interest. Come to think of it, we may have a lot in common.

Photograph by Peking University Chongzuo Biodiversity Research Institute. The accompanying story is here.

Fantasy Island

It is hard to find much to smile about in the news these days what with the U.S. economy in the toilet, sectarian conflicts erupting throughout the world, and nature following its own rhythms and paths to devastating destruction. And so when I saw this picture featured front and center on the NYT website yesterday with the headline “A Vision of Tourist Bliss in Baghdad’s Rubble” I broke out in laughter –and then I double-checked the URL to make sure I hadn’t inadvertently clicked on the website for The Onion.

The man we are looking at is Humoud Yakobi, the head of Iraq’s Board of Tourism, who is looking to convert a small, bombed out island in the Tigris River and within sight of the Green Zone into a fantasy island getaway that would include a “six star” hotel, an amusement park, and luxury villas “built in the architectural style of the Ottoman Empire-era buildings in Old Baghdad.” It would be topped off with – and I kid you not – the “Tigris Woods Golf and Country Club.” The only thing missing, it would seem, is Ricardo Montalban’s “Mr. Roarke” and his sidekick Tattoo. The problem, it seems, is not only finding financial backers to fund the 4.5 billion dollars to underwrite the enterprise, but reckoning with the fact that the target audience—Western tourists—tend to be “sensitive to bombings and things like that” (at least in the opinion of the head of the media relations department of Iraq’s tourism board).

The return to normalcy will surely require venture capitalists willing to take risks on Baghdad’s future and so perhaps we should not be overly cynical here. And yet it is hard to be anything but cynical when the NYT’s “Week in Review” features another story that presumes to underscore the first stages of the return to “calm” and “normal” with a photograph of a mother and child walking about safely in a mixed Sunni-Shiite neighborhood:

Of course, one cannot look beyond the edges of the photographic frame, and so it is impossible to see what, if anything, enables or secures the apparent calm and safety. And as if to acknowledge this absence the NYT slips in two small clickable photographs sutured together in a sidebar labeled “Street Scenes”:

It is important, I think, that the two images function as a vertical diptych, forcing the viewer to take them in seriatum as part of a coherent narrative. The top photograph, the caption tells us, shows members of the “Awakening Council” controlling a local “checkpoint.” The bottom photograph is a car bombing from “early 2007” and is captioned as a once “frequent” scene. The implication then is that the only thing that stands between the bombed out cars and the scene of relative calm in the Sunni-Shiite neighborhood are these local militias.

This logic of the visual narrative is impeccable and if we stop here we might be inclined to read the story as designed to animate support for U.S. policy and the Bush administration’s Pollyanna conclusion that “the surge” has helped Iraq recover its middle American, Main Street calm. But I think another possibility has to be considered. For surely one implication of the visual logic has to be that just as one needs to look outside of the frame of the first photograph to discover what might be supporting the relative calm, one needs equally to look outside of the diptych to discover what supports the Awakening Councils—which are, after all, groups of former Sunni insurgents funded as mercenaries by the U.S. government as part of a “hearts and minds” campaign –and to wonder what will happen when that support dissipates.

The answer to this question is by no means clear, but given the history of this region one has to assume on par that the return to sectarian violence is a very real likelihood. And so we come back to the article that reports Hamoud Yakobi’s plans to build a luxury, tourist retreat on an island in the Tigris River. It really is an absurd fantasy, but then again perhaps no more absurd or fantastic than portraying a neighborhood controlled by former insurgents hired as mercenaries by a foreign and occupying government as somehow a return to normalcy. And maybe that was the point all along.

Photo Credits: Max Becherer/Polaris and New York Times; Ali Jasim/Reuters.

Sight Gag: At Last an Answer to the Age Old Question (Why Did the Chicken Cross the Road?)

Photo Credit: Erin Gay/AP, Seattle Times, September 14, 2008

“Sight Gags” is our weekly nod to the ironic and carnivalesque in a vibrant democratic public culture. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course, we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.