Back in September I commented on the allegorical design of the new U.S. passports and focused attention in particular on the opening page, a cornucopia of signs and references to American hegemony. The visual tableau there begins with an image of Baltimore Harbor being “bombarded.” Subtly but noticeably blended into the background so as to encompass both the inside cover and the first page is the American flag. The “alien” force then was the British Army, but the reference to more recent alien bombardments and expressions of the indestructibility of the American banner are hardly veiled. I promised to continue to examine the visual design of the passport and was reminded of this while traveling recently in the U.K.

The last two pages of the new U.S. passport offer an interesting allegorical complement to the opening two pages, and complete a framework for engaging the intervening twenty-seven pages of image and text that activate a history of the American sublime rooted in the nation’s divinely ordained, adventuresome and inventional spirit.

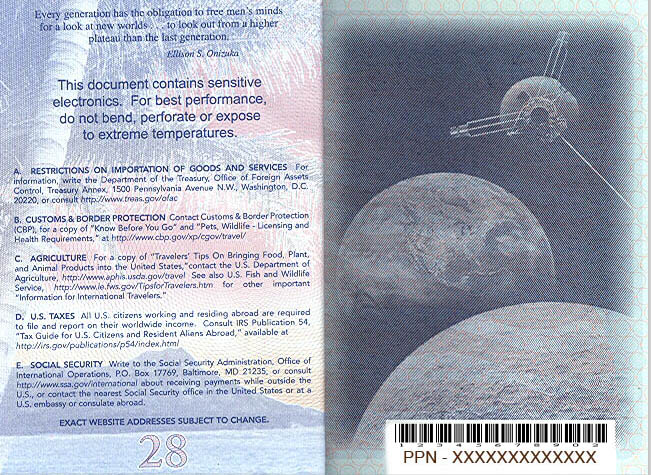

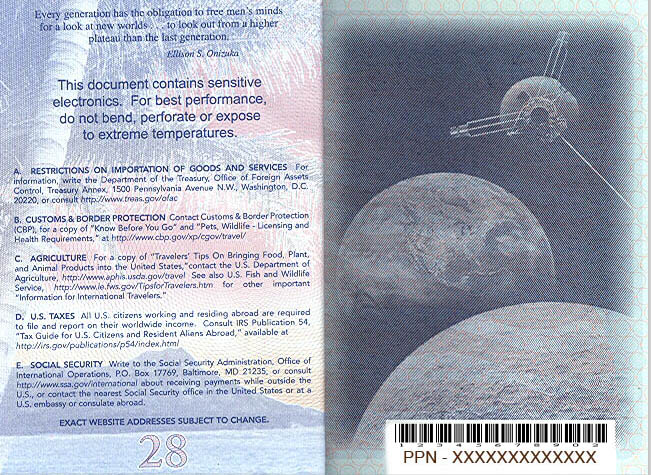

Reading from left-to-right and from top-to-bottom, we first encounter an inscription from Ellison S. Onizuka, “Every generation has the obligation to free men’s minds for a look at new worlds … to look out from a higher plateau than the last generation.” This is quickly followed by a notice, centered and in bold face–and at least twice as large as anything else on the page–indicating that “This document contains sensitive electronics.” The remainder of the page contains addresses “for information” on importation restrictions, customs and border protection, agriculture, U.S. taxes, and social security. All of this information is obscured, more or less like the legalese we ignore and yet are required to sign-off on when we install new software on our computers. Instead, our attention is directed to the connection between “new worlds,” “higher plateau[s],” and “sensitive electronics.” This connection is animated by the photographic illustration that occupies the right hand page and to which our attention is drawn by the formal articulation of the bold faced font of the notice, the reddish hue cast by the sun on the left hand page, and the dark sky of outer space. Here we encounter the earth, centered in the image and, on close inspection, featuring the North and South American land masses. In the foreground is what appears to be the moon. Situated above the two and in-between them, as if the tip of an triangle connecting all three objects, is a satellite. At the bottom of the page is a bar code that corresponds to the passport number.

There is much to comment on here, but what I want to focus on is how the inside back cover is something of a formal “mirror” of the inside front cover, albeit with a difference that coaches the viewer to treat the ideological implications of American exceptionalism as the result of a natural, technological determinism.

The passport begins with a painting and ends with a photograph, the two genres of visual representation framing the historical shift from early to later modernity. The implications of that shift are formalized by the contrast between the quill-and-ink script that sits atop the painting on the inside cover and the computer generated bar code indicating the passport holder’s identification number that rides across the bottom of the photograph on the inside back cover. The shift from “then” to “now”–from painting to photograph, from quill-and-ink to computer generated bar code–is thus marked as a sign of technological progress. Each operates within its own aesthetic register, but the almost perfect symmetry–from left to right, from top to bottom – encourages the viewer to acknowledge a transcendent beauty predicated on the concept of “orderliness.” Notice, for example, how the quill-and-ink script is perfectly measured (at least for its antique medium), and thus anticipates the even more perfectly measured, technologically enabled bar coding on the back page. The shift from “then” to “now” is thus coded aesthetically as a sign of ordered, technological progress.

This aesthetic coding underwrites a politics concerning the relationship between American-style democracy and technology. The key marker here is the reference to “sensitive electronics.” The specific referent is the “electronic chip” embedded in the passport and designed to record the movement of citizens (and others) across borders, but its visual juxtaposition with the satellite looming over the galaxy implies something more. One might expect that technological progress would enable greater latitudes of individual freedom, as is the promise of the “land of the free and the home of the brave,” but here it offers not freedom of movement but panoptic oversight. Such control might be necessary in a world fraught with danger, but the point to notice here is how it is aesthetically domesticated and naturalized.

This post has gone on too long already, but two points are worth noting in this last regard. The first has to do with the way in which the passport is color coded from start to finish. As I indicated above, the inside front cover is encompassed by a washed out American flag that serves as the background to the painting and text, and it bleeds across the margins of the page on the right side, inviting us to turn the page. The color scheme carries its way throughout the passport to the back cover, where we see a tree looming over a land mass in the distance. It doesn’t take too much of a stretch to see that the color coding here might be analogous to the flag unfurled. The tree leans like a flag pole, the leaves recall the dark shield of starts, the red and white hues of the setting sun reminiscent of the alternating stripes. And so the banner originally sewn by a woman is here replicated by nature’s pallet, an almost perfect representation of America’s manifest destiny. But note too that the very last page is severe and abrupt in its difference. Virtually all color is lost as the world is now rendered in black and white; virtually, that is, but not entirely, for on close inspection we can see that the colors of nature/the flag bleed here too, though the threat that they will be washed away remains stark and foreboding. And so, of course, the need to mobilize technology, whatever risks it might invoke to freedom and liberty, seem warranted in the name of security.

But there is more, for we have yet to comment on the somewhat odd quotation from Ellison S. Onizuka that leads off the left hand page. The quotation is odd, less for what is said than for who is doing the talking. Few readers will easily identify Ellison Onizuka, nor could I until I researched it (even though I have previously written extensively about the key event for which Onizuka is known!). Ellison Onizuka was a mission specialist on NASA flight STS 5-L. You know it as the “Challenger” spacecraft. He died along with six other astronauts on January 28, 1986 when, in the famous words of President Reagan, the crew “slipped the surly bonds of earth” to “touch the face of God.” Onizuka’s words, locating the “obligation” of “free men” to “look out from a higher plateau” is thus not just an analogy for the spirit of progress—and the calculated risk that it always entails and yet we work so hard to repress—but operates in an anagogical regiser that puts man (and by implication the technologically advanced American, with his “sensitive electronics”) in proximity to the face of God. In this context the starkness of the black and white world on the facing page takes on an even more sinister, Manichean resonance.

Surely the dangers that the world poses have to be more complicated than this, and yet, here, it seems so natural … almost as if it is destined.

Welcome to 2008.

4 Comments