The photograph above is of 1st Lt. Elizabeth Whiteside. A graduate of the University of Virginia, she has served in the Army Reserve since 2001. Judged to be a “superior Officer” she consistently distinguished herself, first as an executive officer of a support company of 150 soldiers at Walter Reed Hospital, and then as a the platoon leader of the 329th Medical Company at Camp Cropper, a detainee prison near Baghdad which housed 4,000 prisoners, including Saddam Hussein. When Hussein was removed from his cell to be executed, riots ensued and Whiteside stepped up, helping to restore order and ensuring the safety of the doctors in the prison. The next day, she suffered a psychic episode in which she locked herself in a room with a mental health nurse who was also her superior; agitated and noticeably paranoid, Whiteside fired her gun twice into the ceiling. Moments later, with armed soldiers advancing on the door to the room, she pointed her M9 pistol at her own stomach and pulled the trigger. She was returned to Walter Reed Hospital as a patient where she now faces a possible court-martial that could result in life in prison.

Read that last sentence again and let it sink in. It could be the beginning of a tale by Kafka. Tragically, it is an all too real story reported in the Washington Post (12/2/07).

Psychic trauma is certainly one of war’s dirty secrets, a condition all the more troubling when we recognize that even the most conservative estimates maintain that 20% of the more than 1.4 million troops who have or who are serving in Iraq will experience some form of war-induced post-traumatic stress. Indeed, it is hard to process the magnitude of this condition – after all how can one imagine, let alone “show,” 300,000 sufferers of what is characterized as a silent and invisible disease. And yet the tragedy being reported here is not that those who go to war suffer psychic trauma. This is something perhaps even worse: the Pentagon’s abandonment and betrayal of honorable men and women who have voluntarily put their lives on the line to serve their country and who have been seriously damaged by the experience in the process.

In Whiteside’s case the military gave her the option of resigning with a “general under honorable conditions” discharge that would have deprived her of most of her benefits, including medical care. She chose to fight the charges against her instead, and as a result Maj. Stefan Wolfe, the prosecutor for the government, argued last week that she should be court-martialed despite the opinion of the Army’s own surgeon general that Whiteside had experienced a “psychotic, self-destructive episode.” It is hard to imagine what the military can be thinking here, but their position seems utterly stupefying and totally devoid of anything like compassion. If the tragedy of the Vietnam war veteran was that he was abandoned and betrayed by the society-at-large, it seems as if the tragedy of the Iraqi war veteran is that they are being abandoned and betrayed by their own.

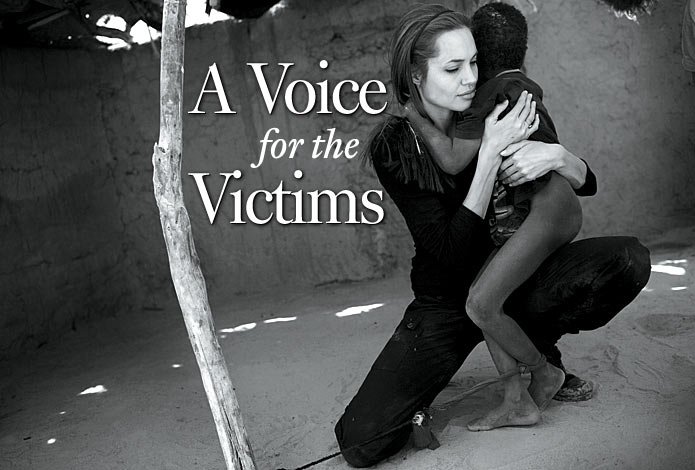

The photograph of Whiteside above is a telling and poignant portrait of the problem. Judged to be a model soldier in every regard up to the very moment of her psychic breakdown, and thus the best that the military has to offer, she is shown here in the hallway of her Walter Reed Guest House as she awaits a decision as to whether or not she will face a court-martial. Standing at attention, but without uniform, she bears the countenance of the “thousand yard stare,“ though it is hard to know if this is the result of her time in Iraq or her more recent “war” with the military. Billeted in the “Walter Reed Guest House,” she is caught in a chasm between being a private citizen and a soldier, neither clearly one nor the other. Illuminated by a yellowing light, her face is nevertheless shrouded by a dark and foreboding shadow; cast in sepia tones, she is locked in a past that she can neither understand nor escape. Thus, her trauma continues. Most of all, she is alone. Completely and utterly deserted by those who should be protecting her. If the aftermath of the Vietnam War taught us anything, it was that such isolation and abandonment is anything but a recipe for psychic healing – not for individuals and not for the culture writ large. And yet the military refuses to see what would appear to be right before its very eyes, insisting that her defense is mere “psychobabble,“ as if shooting oneself in the stomach could be imagined as an act of sanity.

The depth of utter betrayal by the military of its own is magnified by another photograph that is part of the same story. While living with a group of mental outpatients on the grounds of Walter Reed Hospital, Whiteside befriended Sammantha Owen-Ewing, a twenty year old Pfc. who had been “abruptly dismissed from the Army” against the wishes of her doctors and who had lost access to all military benefits, including her medical benefits. Owen-Ewing recently committed suicide and Whiteside traveled to her burial service in Utah. The last picture in the WP photo-essay that chronicles Whiteside’s story is of Owen-Ewing’s casket:

Its contrast with every one of the hundreds of funerals we have seen of military veterans in recent years is marked by the absence of a military honor guard, and, more noticeably still, the American flag. The argument of the photo-essay could not be more eloquent, as the substitution of flowers for the flag underscores both the simple dignity and decorum of a private funeral, as well as well as the military’s indecorous denial of its responsibility to care for its own.

Photo Credit: Michelle du Cille/Washington Post