Jean-Louis Gerome Ferris, “The First Thanksgiving,” circa 1900

Norman Rockwell, Ours … to fight for … Freedom From Want, 1943

(Click on Picture Below)

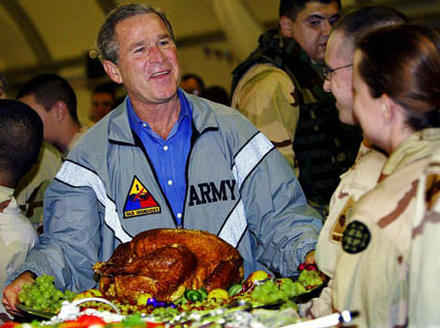

Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP, 2003

(This photograph is no longer available on the AP Website)

![]()

Jean-Louis Gerome Ferris, “The First Thanksgiving,” circa 1900

Norman Rockwell, Ours … to fight for … Freedom From Want, 1943

(Click on Picture Below)

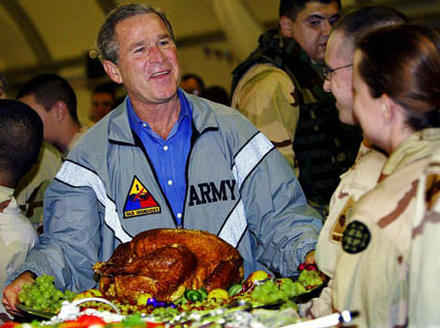

Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP, 2003

(This photograph is no longer available on the AP Website)

![]()

Since my post about Making Nice on a Day of Shame, Michael Mukasey has been confirmed as attorney general. More to the point, yet another attorney general has been confirmed to oversee rather than stop the American institutionalization of torture. Meanwhile, the news has moved on to more important things like the run up to the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade. Along the way, you may have missed the few stories that appeared about an art exhibit that opened recently at the American University Museum in Washington, DC. The exhibition provides the first complete show of Fernando Botero’s 79 painting and drawings of the torture of Iraqis by American soldiers and private contractors at Abu Ghraib prison. Botero’s work draws on the massy bodies of pre-Columbian art, usually regarding cheery subjects. As Arthur Danto at The Nation remarked on the horrors of Abu Ghraib, “if any artist was to re-enact this theater of cruelty, Botero did not seem cut out for the job.” Others in the know will have shared that thought, until they saw what Botero has done through paintings such as this:

Botero has avoided reproducing those images that have circulated so widely: the cowled, cruciform victim hooked up to wires, or Lynndie England holding a leash or pointing her cocked hands. Instead, he has taken pains to depict scenes that were captured by print journalism. In fact, a Google search will turn up photographs of many of the abuses marked in his exhibition, but that is beside the point. If nothing else, Botero’s paintings provide another attempt to provoke renewed public revulsion, reflection, and debate. There certainly is need for that as the initial photographs are becoming either icons or curiosities. His images also place the scandal into the archive of Western painting while drawing on that tradition to strengthen protest; so it is that the exhibition is compared to works such as Guernica, among others.

One question is whether painting provides a unique form of documentary witness, one characterized by its superior capacity for moral response. Danto, for example, argues that “Botero’s images, by contrast [to the Abu Ghraib photographs], establish a visceral sense of identification with the victims, whose suffering we are compelled to internalize and make vicariously our own. As Botero once remarked: A painter can do things a photographer can’t do, because a painter can make the invisible visible.’ What is invisible is the felt anguish of humiliation, and of pain. Photographs can only show what is visible; what Susan Sontag memorably called the ‘pain of others’ lies outside their reach. But it can be conveyed in painting, as Botero’s Abu Ghraib series reminds us, for the limits of photography are not the limits of art.”

Although the last clause is certainly true, I find this argument to be bizarre, and not only because it contradicts his claim, earlier in the same article, that “it was hard to imagine that paintings by anyone could convey the horrors of Abu Ghraib as well as–much less better than–the photographs themselves.” Of course, once you invoke Sontag, you had better be prepared to contradict yourself. I’m not questioning Danto’s subjective reactions, of course, but I know that he is wrong about mine. And I have to wonder how anyone could think that people were not feeling the pain of others when they reacted with disgust, shame, and outrage as they saw the photographs. Millions of people have reacted that way, which is precisely why the photos made torture a major topic of public debate. One hypothesis is that it may be difficult for those, such as Danto and Sontag, who are steeped in the pictorial traditions of the fine arts to identify with or respond emotionally to photographs. Fortunately, that is not true for the rest of us.

I won’t go on, for surely there is something obscene about turning the depiction of evil into an intramural debate about aesthetics. Whatever the art, there is need to confront the horrors–and the indifference–of our time. Botero has done that, and his artistic medium and style are important forms of witness. He asks, “Is this what 400 years of modern Euro-American civilization has come to? Is the indigenous body still being tortured?”

Look again at the painting. Keep it in mind when administration officials and neocon pundits obfuscate about torture, or when the leading Republican candidates and various editorial cartoonists joke about torture. This holiday weekend let’s not only give thanks for the good life with friends and family, but also renew our resolve to stop state terrorism.

You can see more of the images from the exhibition here and here.

Last week I posted about this photograph of Reserve Board Chairman Bernanke preparing to speak before a congressional committee on economics, contrasting the ritualistic, faux-piety of the scene with the photographic representation of the gluttonous impiety of Marshall Whittey, a sales manager for a floor and tile company in Reno, Nevada who was feeling the “pinch” of the equity credit crisis that left him “eating in” more often.

I suggested that the juxtaposition of images, published as part of separate articles in the NYT on the same day, invited a civic attitude that located the problem of the economy in the psychology of private life—individuals making bad economic decisions—rather than in any inherent systemic problems with the so-called “free market.” One reader wondered if the affect of the Bernanke picture would change if we were to juxtapose it with a more tragic and typical representation of a foreclosure or eviction; another reader pondered whether it was even possible to represent systemic social problems visually without reducing them to individuals in a manner that might tend to discourage collective action. These are both excellent questions that deserve a second look.

Several days following the Bernanke’s report to Congress the NYT published this photograph as the lead-off to an article in its Week in Review:

The caption reads “EX HOMEOWNER Esta Alchino of Orlando, Fla., was late paying her mortgage and lost her house.” Both this photograph and the one of Whittey point to individuals caught in the equity crisis, of course, but in this case the photograph is framed by the title of the article, “What’s Behind the Race Gap?” The difference is pointed, for the earlier article focuses on how an acquistive individual, is being “pinched” by the economy and his risky economic decisions; here our attention is directed to Esta Alchino as a representative of racial difference, and thus, presumably, a systemic state or condition, i.e., racial discrimination.

The tension between the two photographs is particularly conspicuous. He sits in his home amongst his prized possessions, she stands in front of (or is it behind?) what used to be her home with nothing but the clothes on her back. Both look out of the frame to the viewer’s left, what we conventionally understand to be the past, but what they purport to see behind them is somewhat different as he exudes a devil may care attitude, a gambler who made poor choices but will be back to play again as soon as he has recovers his stake, as is the promise of the American dream; she wipes tears away in contemplation of a profound loss as she looks back on a national history of racism in which the “dream” seems always out of reach for our dark skinned citizens. The key to the two photographs might well be how the citizens/actors are located within their respective scenes. His home is large, lavishly adorned, and full of light with the promise of more by simply opening the shades behind him—a simple personal choice; her former home is small and dilapidated, lacking any adornment whatsoever, and drab by almost any standard, even as it sits in the full light of day. He is the lord of his manor, accompanied by his dogs; she is completely isolated and disconnected, visually homeless and without any sort of shelter, either physical or symbolic. She is literally alone in the world.

The question is, how might we understand this later photograph as an indication of a systemic problem? What makes Alchino more an illustration of racial discrimination than simply an ineffective liberal economic actor? This is no easy question, but part of an answer can be found in considering how Alchino is framed as something like an “individuated aggregate,” an individual posed to stand in for an entire class or race of people. Here that is marked in part by the fact that she is never once mentioned in the accompanying article that features two neighborhoods in Detroit, a city that is a fair distance from Orlando. We know nothing about her beyond the fact of her race and that she could not make her mortgage payment. We are never even told why she could not make the payment, though we are told that on par high-cost subprime mortgages tend to be concentrated in “largely black and Hispanic neighborhoods.” As such, she stands in as a victim of circumstance, and as the article underscores, the circumstance is a potent and often ignored systemic racism.

The additional question is how we might understand the portrait of Bernanke differently in comparison to the image of Alchino, who is arguably more representative of those harmed by the equity crisis than Whittey. Here, of course, Bernanke’s countenance now changes some, as his prayerful pose seems sorrowful and contrite—worried less about the difficulties of his own job, than about the conditions of people like Alchino. But of course, this comparison is problematic as well, for if we go back to the words he spoke that day, there is nothing that indicates a concern for systemic problems of any kind, either rooted in economic policy or more deeply in the kind of implicit de facto racial profiling that seems to be pronounced within the mortgage industry. What the different comparison of the images does speak to is the need for more sustained consideration of how any particular photograph operates within the visual economies in which it appears.

Photo Credits: Doug Mills/New York Times; Joe Raedle/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

![]()

Eddie Adams’ photo of General Nguyen Nguc Loan executing a bound Vietcong prisoner of war remains one of the searing indictments of the criminal conduct of that war.

Adams went to his grave insisting that the photograph was being misused because the execution was a justifiable act in the context of the battle for Saigon. That may be so, but the literal dimension of the image has from the beginning been irrelevant to its distribution, interpretation, and acclaim. The photograph’s rhetorical power comes from its symbolic and ethical implications in respect to the justification of the war itself. Whatever else was happening on the street that day, this image provides stunning illustration that the war was spiraling far out of control–militarily, politically, and morally.

If this interpretation of the photograph is valid, it nonetheless remains one of many. As John and I elaborate in No Caption Needed, iconic images are important not only because of the role the images play at the time of their initial distribution, but also subsequently as they become templates for artistic imitation and improvisation across a wide range of media, arts, topics, and standpoints. This image from a recent art fair in New York City is only the latest example:

According to the review of the show, you are looking at Xiang Jing’s “Bang!” (2002), a work in painted fiberglass. That this image was selected from the hundreds at the show probably is testament to the continuing power of the iconic image, although we also should recognize the reviewer’s rationale: “Ms. Xiang’s sculpture embodies the mood of the first Asian Contemporary Art Fair . . . Fizzy and entertaining on the surface, it has a disquieting underside.” Likewise, the reviewer remarks that “the playful surface of ‘Bang!’ masks a half-repressed trauma.”

I’m not so sure that anything is being “masked” or “half-repressed.” The language of art criticism, and not least its depth psychology, really doesn’t get this one right. There is no underside to this image: the horror is right there on the fizzy surface.

One might wonder why Adams’ photograph was mentioned at all. Jing’s artwork has reversed virtually everything of note in the original image: the figures are women instead of men, civilians instead of soldiers, wearing stylish contemporary clothes instead of the de facto uniforms of the past, highly expressive instead of stony faced or having a tight grimace, hairless instead of having hair, positioned right to left instead of left to right, backed into a corner instead of an open street, colored statues rather than people in a black and white photograph, and fictional instead of real. The “killer” is even more obviously transformed, as she is using a finger instead of a gun, facing the viewer, looking away from the victim, and smiling. And why is a Chinese artist appropriating American photojournalism about the Vietnam War to depict contemporary young women?

Just as the meaning of the iconic photograph quickly escaped the photographer’s sense of scene, our response to this work of art is not likely to be tied to knowledge of the artist’s intentions. If there is no intended connection between the two images, then the sculpture still is troubling, if somewhat puzzling. If the viewer makes the connection, intended or not, part of the experience of the artwork, then it instantly becomes deeply disturbing. Now the social violence of adolescence acquires the killing power of warfare, while the passage of time suggests that killing is becoming ever more casual, routine, normative, and even enjoyable. And just as the traumatic image from Vietnam lives on it the contemporary artwork, so does a history of war, dislocation, and layered betrayals continue to shape contemporary life, not least in societies experiencing both hidden violence and comprehensive modernization.

Don’t be too quick to guess which nation I might be referring to. On reflection, it can make sense after all to speak of surface and depth. “Bang!” might place the medium of photojournalism under the medium of sculptural art, as with a palimpsest, to suggest that under the fizzy surface of modern consumer culture there still are layers of personal and collective violence.

Finally, a footnote: The title “Bang!” may be a double allusion, including both the Adams photograph and another iconic image from the Vietnam War: the photograph of a naked girl running away from the napalm drop on her village. The name of the village was Trảng Bàng.

Photo Credit: Al Lowe

Our primary goal with this blog is to talk about the ways in which photojournalism contributes to a vital democratic public culture. Much of the time that means we are focusing on what purport to be more or less serious matters. But as John Stewart and Stephen Colbert often remind us, democracy needs irony, parody, and pure silliness as much as it needs serious contemplation. For our part, we will dedicate our Sunday posts to putting some of that silliness on display in what we call “sight gags,” democracy’s nod to the carnivalesque. Sometimes we will post pictures we’ve taken, or that have been contributed by others, or that we just happen to stumble across as we navigate our very visual public culture. And we won’t just be limited to photography, as a robust democratic visual culture consists of much more. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.

Call for Papers

Home, School, Play, Work: The Visual and Textual Worlds of Children

October 31 and November 1, 2008

Worcester, Massachusetts

The Center for Historic American Visual Culture (CHAViC) and the Program in the History of the Book in American Culture (PHBAC) at the American Antiquarian Society seek papers that explore the visual and textual worlds of children in America from 1700 to 1900. We welcome proposals that address the creation, circulation, and reception of print, manuscript, and other materials produced for, by, or about children.

Submissions may address any aspect of eighteenth and nineteenth-century textual, visual, or material culture that relate to the experience or representation of childhood. Suggested topics include popular prints for or of children, board and card games, children’s book illustration, visual aspects of children’s books and magazines, early photography and children, performing children (theater, dance, the circus), dolls and puppets, child workers in art and printing industries, images of children and race, representations of childhood sexuality, the architecture of childhood spaces (schoolrooms, nurseries), children’s clothing, children’s appropriation of commodities, children’s handiwork (samplers, dolls, toys), and theories of visuality or textuality and childhood.

Please send a one-page proposal for a 20-minute paper and a brief CV by January 10, 2008, to:

Georgia Barnhill, Director of CHAViC

185 Salisbury Street

Worcester, Massachusetts 01609-1634

gbarnhill@mwa.org

About the Conference Committee

The conference committee is chaired by Patricia Crain, professor of English at New York University. Other members include Joshua Brown, executive director of the American Social History Project at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York; Martin Bruckner, professor of English, University of Delaware; Andrea Immel, curator of the Cotsen Children’s Library, Princeton University Library; Paula Petrik, professor of history and art history at George Mason University; Laura Wasowicz, curator of children’s literature at AAS; Caroline Sloat, AAS director of scholarly publications; and Georgia Barnhill, curator of graphic arts and director of CHAViC.

This photograph from a hospital in Iraq has all the elements of comedy except the laughter.

A man and a boy–probably father and son–are awaiting treatment following a suicide truck bomb attack. They are the lucky ones.

I’ve posted before on the normalization of war, and recently on the importance of seeing and valuing the little things in life to resist war’s empire. This photo is both engaging and troubling precisely because it rests on the cusp between those two attitudes. On the one hand, it is a hard news photograph that documents the arbitrary, unjust violence of war. On the other hand, it is a soft news photograph that draws on the techniques of Life Magazine human interest portraiture.

The hard news photo shows civilians drenched in their own blood, having to make do with improvised bandages while waiting for care in an overburdened and decaying hospital. The soft news photo shows two social types in all too typical poses: the boy in t-shirt and blue jeans peeking out from the mess he’s made, as if sitting in the principal’s office at school. The adult holding a compress to his aching head as he wearily, dutifully accepts yet another of the responsibilities of parenting. The one furtively studies the adults around him while wondering if he’s going to catch it. The other makes the call cementing his complicity in the mess, and, oy, what a headache.

If this were the only photograph of the civil war, there would be much to fault. Why make light of violence; aren’t we denying their suffering and our own culpability? Surely we could be shown more of the horror of war and the arrogance, viciousness, allegiances, and betrayals that are its cause. This photo is part of a very large archive, however, and so it has a different role to play.

I don’t want to come down decisively on one side or the other regarding the photo’s ambiguity. I do want to feature something else, something that may be the reason the photo is ambiguous and why that itself can be a resource for photojournalism and public understanding. I think the humor in the photo–the comedy without laughter–is a testament to the humanity and dignity of the ordinary Iraqi citizen. Look again at the jeans, t-shirt, slouching posture, and expression of the boy, and the man’s sweater, watch, cellphone, and richly complicated look of responsibility: these are the habits of people not yet remade by war. That a man carefully buttoned his cuffs and put a sweater on, perhaps because nagged to do so, is a commitment to normalcy. That he can make the call as if after a car accident, exasperated but relieved–and not terrorized–that is an achievement.

Once again, the war against war can be seen in the details, and photography has to risk banalty and sentimentality to tell that story. What remains is for the rest of us to see it for what it is, and not simply conclude that war is a part of life and really not so bad after all. To do that would be another betrayal.

Photograph by Emad Matti/Associated Press and the Washington Post.

For many of us, Veterans Day has come and gone. That was, let’s see, Monday, right? Working parents knew if their kids were out of school, and others missed getting the mail, but whatever the inconvenience, the day was just that–a day. Even among those few who attended the commemoration ceremonies, the time spent there will have been brief. And so it is that a well-intentioned civic ritual perpetuates a lie. For those who grieve, there is no Veterans Day. To understand this painful truth, we need look no farther than this photograph:

The caption read, “Terry Giannoni (right) found names of friends of the wall of dead at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Plaza in Chicago on Sunday.” (The official day of commemoration was Sunday, November 11, with Monday the 12th becoming the federal holiday.) I’m not sure which is more revealing, the simple statement that he found “the names of friends” or the heavy sadness in his grim expression and hunched, protective posture. Those soldiers have been dead for over thirty years, and yet they are still remembered as friends. Their deaths still weigh down the heart. Those who once were laughter and good times and the simple pleasure of being together, have lingered long after as loss, regret, and who knows what other difficult emotions. And if friends still grieve, imagine how parents and lovers have suffered. War never lasts a day; it lasts forever.

The photograph is eloquent because of how it draws together simple things to reveal the truth of war’s continuing harmfulness. This is a local memorial with ordinary people–no national site, color guard, or officials–and so the emotional tone is honest and direct. Those feelings are the more deeply sensed for not being highly expressive, and that mute recognition is reflected in the simple decor and design of the memorial. The numbing isolation of grief is communicated by the distances between the two men in the picture and between Giannoni and the panel of names, while the black/white divide on the wall reminds us of the terrible finality of death.

There is one more thing: the way that time saturates the image. Giannoni’s grey/white hair and craggy features mark the years since the Vietnam War. The man in the left rear reinforces this passage: long hair now comes with a bald spot, and the blue jeans and jacket now are worn on a middle-aged body. On the panel behind them we can see two dates: 1969 and 1970. These were the first two years of the Nixon administration, the first two years of the “secret plan” to bring us “peace with honor,” a plan that brought an additional 20,000+ American deaths and somewhere around a million Vietnamese deaths to secure disengagement on terms very similar to those available in 1968. Time was not on anyone’s side in Vietnam. Since then, it has carried grief and anger relentlessly through the years.

Photograph by Chuck Berman/Chicago Tribune.

This image is at once unusual and deeply familiar, no matter where you imagine it taking place.

The incongruity comes, of course, from seeing a dude in gangsta attire going down a buffet line within what looks like the perfect example of the Generic Hotel banquet room. More to the point, this guy is out of place, whether the place is Libya, where he actually was, or Atlanta or Chicago or any other city center.

For all that, the scene will be all too familiar to many viewers. This is the generic modernity inhabited by the middle class whether they are at work or at a wedding or some other weekend event. If you’ve seen one room like this, you’ve seen them all. And for all the effort that goes into pretending that today’s buffet is better than the rest, it rarely is. This one doesn’t even make the effort. The tackiness of the scene becomes obvious because of how he looks–that cheap jacket makes the aluminum warmers and stacked plates all the more obvious–while the long view exposing the table legs and chair backs makes all the decor seem all too typical.

And this is where things get interesting. The New York Times story captioned by the picture was titled “Rebel Unity is Scarce at the Darfur Talks in Libya.” It seems that the big fish boycotted the peace conference, leaving only small fry like our man at the buffet line. No one was interested in talking with the lesser lords of the desert, who were left to kill time in the hotel. In fact, the story reported that those present usually descended on the buffets together, but the photographer obviously wanted to show something other than eating.

So, what is being shown? It could be that small tribal leaders are out of place in modern diplomatic settings. Since he doesn’t really belong there–as you can see just by looking at him–then he ought to go back to the Darfur “street” from whence he came. In short, he shouldn’t have presumed to be there at all. (Never mind that he will have come at personal inconvenience, expense, and risk, and that he probably is able to wreak havoc somewhere if so inclined.)

That interpretation might do, but I think the photograph deconstructs on precisely that point. For one, he is behaving exactly as he should; from the measured manner in which he is holding the serving tongs, it looks as though he’s been through a buffet line many times. More important, the tackiness of the rest of the scene speaks volumes. The problem isn’t that he’s there, but that the room is otherwise empty (save for the single waiter at the end of the table). The room itself looks like a mere shell, an artificial trompe l’oeil of modern life superimposed on the backdrop of the desert, clan politics, and constant cycles of violence. Perhaps the conference would have worked had the room been full of all the leaders and their entourages, but this photograph hints otherwise.

Maybe the problem isn’t the homeboy but the hotel. More precisely, perhaps the problem is that peace is no more to be brokered in the neutral space of Generic Modernity than it could be found in the dangerous places of the Darfur borderlands. Nor are the scenes themselves the problem. The hotel, like the desert, brings with it a particular conception of politics, negotiation, and peace. Each activates different modes of organization, modes of speech, and images of the future. My guess is that if peace is to come to Darfur, and to many other places around the world, those involved will have to find another place to meet that is neither the war zone nor the modern hotel. That is, they will have to find another way to talk and think together that is neither entirely outside of modernity nor within its most typical structures and assumptions.

You will have seen the recent photographs of Pakistani lawyers demonstrating in the streets of Islamabad and then being punched, kicked, clubbed, and hauled off to jail. You won’t see what will happen to them in the Pakistani prisons, but that surely will include more brutality and probably torture. And what is incredible is that the demonstrators will have known that when they went into the streets. Their heroism is a rare and beautiful thing that has not been captured fully by any photo that I’ve seen.

But they are more than heroes–they are lawyers who have been working for years on behalf of the rule of law and liberal-democratic constitutional government. And they are less than heroes–ordinary people struggling to achieve something action heroes never see: the normal life of a modern civil society. That’s why I like this photo:

The New York Times caption said, ” Lawyers meeting on Monday at the bar association offices in the Pakistani capital, Islamabad.” This image captures both the pervasive weight of oppression and the incredible ordinariness of life as it is when people are allowed to live and work together without fear.

The steep odds and dark prospect before them are evident in the expression of the man in the foreground as that is reinforced by the serious faces all around the room. His expression shows that there are no good options, and that all that they have could be slipping away, and that he knows this. He has not caved, however: his forward posture, cocked head, and intense look suggest a man still capable of action, and the crowded presence of his colleagues all around the room is mute testimony to that resolve.

Heroism is seen in broad strokes, and what I love about this photograph are the many small details. The two thumbs touching in the right foreground, a practiced gesture of waiting. The sliver of leg showing between sock and pants cuff; the coffee cup and water glasses abandoned on the table; the dark furniture and wood paneling seen in almost every lawyer’s office in the world. The clothes and decor are nice–Pakistan does have a middle class—but they are above all conventional, the ordinary background of modernity.

What unites these opposing attitudes of normalcy and oppression is the fact that those in the room are waiting. Images, like texts but often even more so, are condensed interactions. If nothing else, they structure a relationship between the subject of the picture and the viewer; often they depict patterns of interaction that can resonate outside the frame. The people in this photograph are waiting, and that can evoke many contexts: they could be in a doctor’s waiting room or a funeral parlor or a green room or a bomb shelter. They could be waiting because someone is late or because someone is missing. They could be hoping that late results would reverse the tide of electoral defeat, or for the verdict in a court case, or for the results of an exam or an interview. They could be at a consulate anywhere in the world. If there were no exit, they could be in Hell.

Thus, the photograph is above all else an image of waiting, and with that it evokes both terror and a promise. The terror is that they are already doing what they will be doing in prison: waiting for something much worse to come. The promise is like that sliver of bare leg: the hope that some day, if others would join their fight for a liberal democratic society, they would be able to enjoy a world where one is secure enough to suffer only boredom and the occasional fashion mistake.

We need to continue to see the familiar images of street demonstrations, but we need photographs like this one of the silent spaces of political life. Then perhaps the professional class in this country can see themselves in the picture. Over here, lawyers know they are not “hired guns” or “ambulance chasers.” I hope they can look at this picture and understand that their colleagues in Islamabad are not “extremists and radicals.” They are heroes, but we should stand by them because they are ordinary people who should not have to be heroic.

Photograph by John Moore/Getty Images.