I don’t like to belabor a point, but as long as a few Republican senators stonewall any serious attempt to withdraw from the war in Iraq, the press and the rest of us will have to keep up the drumbeat for change. So we have yet another set of images from Iraq, these in conjunction with a special series in the Chicago Tribune that followed a troop of soldiers Inside the Surge. The photo essay shows the troops in camp, on the move, playing with kids in the street, and the like. The usual stuff of embedded coverage. And as happens often enough, they catch something of the other side of the myth of GIs handing out candy bars. Like this:

The caption reads, “The sister and nephew of a suspected insurgent cry during a nighttime raid of a house by soldiers in Bonecrusher Troop.” Hey, someone might say, it could all be an act. Ok, it could, although we are told later in the story that the suspect was released. And even if mom is acting, or perhaps trying to be reasonable, look closely at the boy. He is terrified. Hunching down into himself, close to crumpling, his face a mask of fear and shame and pain; he will not forget this night.

I’m also struck by several other elements in the photo. One is the standard of living. These are not the wretched poor of the “Arab street.” It is much more likely that they are middle class, exactly the people who were least likely to object to the changes promised by the Bush administration. Their usual preoccupation of the evening probably would be not building bombs but rather keeping the boy at his homework. I also notice that the room is so clean and spare. The emptiness of the room might be an indirect sign of the boredom and general social deprivation that is the common experience of so many civilians trapped in the war zone. In order to avoid the danger of life outside, they are confined to a few rooms and left with each other and the TV, if the power is on.

And then there is the gun in the right foreground. (That gun has appeared more than once in American photojournalism, as John noted here.) Sure, it’s pointed down, but were it to be raised boy and mother would be right in the immediate line of fire. No wonder the boy is afraid. Cordoned by soldiers on each side, mother and child beseech one who turns his back to them while the other holds them under the gun.

And they are not the only soldiers in the house. Here is another photo:

The caption reads, “Staff Sgt. Stephen Yacapin of Bonecrusher Troop’s 3rd Platoon searches a bedroom for weapons or other evidence of insurgent activity during a raid in Baghdad.” Like the mythical WMDs, he will not find weapons here either. We can see what does turn up, including a purple comforter, a hairbrush and comb, hair gels or something of that sort, snapshots of family or friends, a magazine or folder in English, a purse–not exactly the raw materials of a terrorist cell. We also can see that he’s tearing the room apart. Maybe he’s going to put everything back in place, but it is going to be hard to stack the drawers again and put square corners on the bedsheets while outfitted like a storm trooper from Star Wars. I do not question his need to be outfitted for combat, but what is the Bonecrusher Troop doing in anyone’s bedroom?

And from the look of it, it could be anyone’s bedroom. I’ll bet I could get everything there from Target. Putting that room back together may not be hard to do, and the mess may be be a great harm, but surely they will feel that this raid was a violation of their intimate space, for that is what has happened.

These photos are not the whole story, nor are they any more true literally that those that show soldiers being friendly. But they should remind us that the Iraqi citizens’ experience of the US occupation is deeply personal. Pundits who pretend to ponder the great question of Why They Hate Us need look no farther then these images. This is not about the clash of civilizations, the supposed oxymoron of Islamic democracy, or any other Big Idea. This is about being terrified in one’s own home.

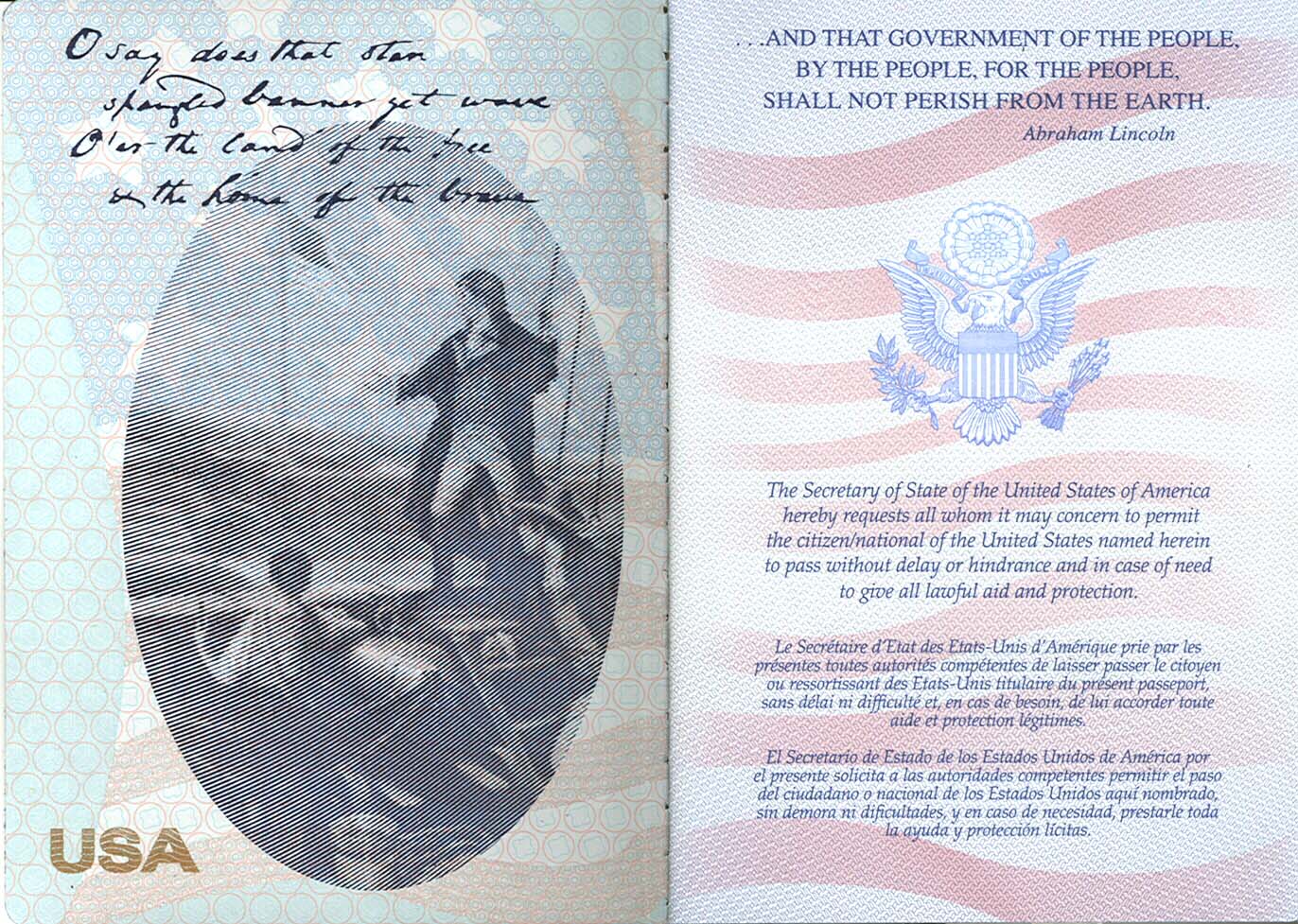

You would think Americans could empathize: Recall these words from the Declaration of Independence:

He [the King of Great Britain] has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his assent to their acts of pretended legislation:

For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us . . .

Of course, many Americans do understand, in part because they have seen photographs like these. The general public is not the problem.

Photographs by Kuni Takahesi for the Chicago Tribune.

3 Comments