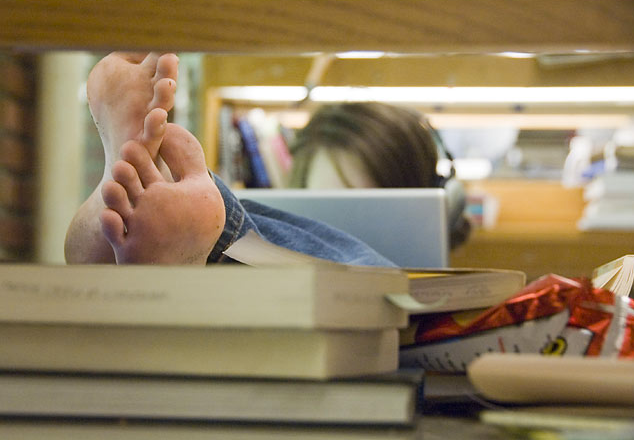

I pulled this photo out of the Images in the News at the Chicago Tribune online a month or so ago:

Unfortunately, I’ve lost the photo citation, but maybe that will turn up. I’ve decided that the picture is too striking to be buried for want of a footnote. The paper knew as much, for the photograph certainly isn’t “News.” You are looking at four river otters swimming, something they do every day.

The image captures much more than four otters in the water. The silver sheen fuses light, water, and animals into a single, perfectly unified event. The otters are completely at home in the water, moving together with the flow of the river, the flow of all of nature’s energies. And yet they also look like they are made of molten metal, crafted forms emerging out of a bath of silver alloy. Caption it “Metal World” and you have a movie still. More seriously, the photograph alludes to the art and history of photography, as if a silver gelatin substrate has been beautifully brought to the surface of the image.

Whether you see the aesthetic unity of the image as the eloquence of nature or art, the question remains of what it has to say. And the otters aren’t so much at home as on the move. They seem to push purposively through the water, tightly coordinated, like a team or other work group. The four are entrained, and entrainment is both an important feature of social life and an artistic technique in photojournalism. Entrainment also can be suggested by mechanical reproduction of the same image, so once again the image channels the art, in this case, the aesthetic element and cultural anxiety marked by Walter Benjamin’s famous essay on “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” This photograph provides the multiplied image within the frame rather than through reproduction of the photograph itself (as I’ve done), but it is the more fitting for that.

The photograph fundamentally isn’t about itself, however. I think the uncanny quality comes from the combination of the light, the entrainment, and the implicit analogy between one species and another. They are coordinated very much as humans can be: working together while each still exhibiting individuality. Although each is looking in a different direction, these four animals may look much more uniform than individuated, but that may be due to our inability to see them from inside their own social experience. Is the difference between humans and otters that they are much the same while we are each an individual person, or is that belief merely the mistaken result of our ignorance, our inability to enter their world? The photograph, which may have been selected for merely “aesthetic” reasons, poses significant questions about who we are and what we value.

Such comparisons may be more than academic exercises. The river otters are among the many species endangered with extinction. Seeing them as if they were artificial otters in some liquid metal bath of the future, perfect reproductions of the extinct species, makes me realize that they then could just as well be a team of specialized workers finely engineered for the industrial environment of that world. Looking at the picture again, I see the complexity and beauty of nature, and also a possible future that includes not only the otter’s extinction but ours.