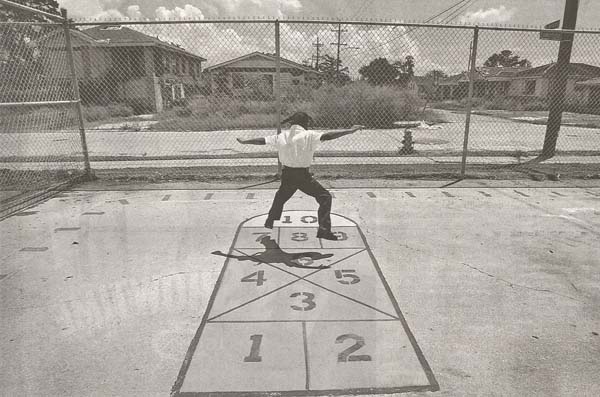

The lemonade stand. It is as American as apple pie, a time-honored tradition deeply rooted in the American dream and its Horatio Alger ethos. All it takes is an old soapbox or small table; some lemons, sugar, and ice; a few paper cups; a hand scrawled sign and, of course, some good old American initiative. For many children it is their first encounter with the spirit of capitalism, and hey, even if there isn’t much monetary profit at .10¢ or even .25¢ a cup, there is the social capital gained by cooperating with friends and neighbors, and learning how to encounter the marketplace, both of which may be far more important civic lessons.

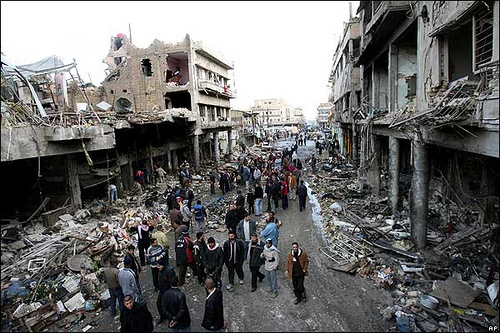

A safe and open marketplace is essential to a vital democratic public culture. What better way, one might then imagine, to demonstrate the success of our military surge in Iraq than to show a safe marketplace operating in the Al-Anbar Province, one of the most volatile and dangerous places in all of Iraq. And more, what better way to show that safety than with “a young Iraqi boy selling lemonade in the town of Ramadi …”

Prior to the surge, Al-Anbar Province had been the “hub of [the] Sunni insurgency.” But apparently not anymore, as over 6,000 U.S. troops walk the streets, along with a growing Iraqi police force and tribes of “provincial volunteers.” That the police force is beleaguered and the volunteers bear a striking resemblance to vigilante groups doesn’t seem to matter, for here in Ramadi, seventy miles west of Baghdad on the Euphrates River, safety and commerce seem to rule as the marketplace is open for commerce and, as the caption tells us, a young boy sells lemonade. At least according to the caption, one might imagine themselves on a street corner in middle America.

Upon a second glance, however, it is not clear that all is well. The eye is drawn initially to the boy who we might expect to see smiling for the camera or making a sales pitch to a potential customer. But there is none of that. The tentative and concerned look on his face and the gestural attitude of his body suggest that he is far from at ease with the situation. And with good reason, for the soldier and his weapon pose an ominous presence as they simultaneously frame and obscure the scene—perhaps a metaphor for U.S. military presence in Iraq writ large. Indeed, one has to wonder how truly safe things can be if something on the order of international martial law is needed to insure the everyday routines of domestic commercial life.

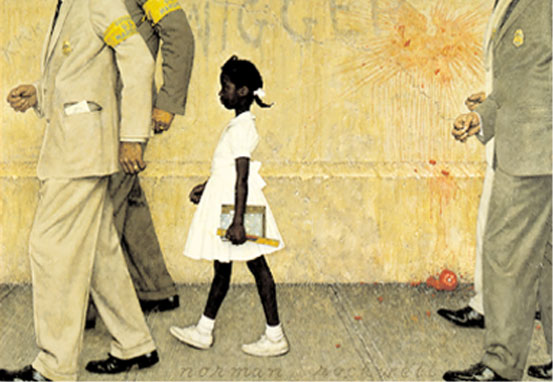

The contrast between the two images points in some measure to the problem of the project of exporting liberal democracy. A liberal democratic public culture relies upon the sense of trust that is generated by the kind of social capital we see being invested in the photograph of the two young girls at the top (or in any of the hundreds of pictures that you will encounter if you google “lemonade stand”). Such images are tinged with nostalgia and too easily romanticize our bourgeois and middle class sensibilities, and we need to be very careful about being too proud of ourselves in this regard, but the sense of trust and cooperation that they depict is necessary to such a politics. It is not the only thing, of course—the opportunity for free and open dissent come to mind as no less important—but it is essential. And it is hardly the cultural or civic attitude that is generated by a massive and sustained foreign military presence or roving tribes of provincial volunteers. To accent the point, one need only visualize the scene of the two girls at the top—innocent, pure, and white—with the soldier and his weapon framing and overshadowing the scene. It is virtually unimaginable.

Photo Credits: Central Ohio Center For Education, Richard Mills/The Times

![]()