Because it’s the photographs’ fault, apparently.

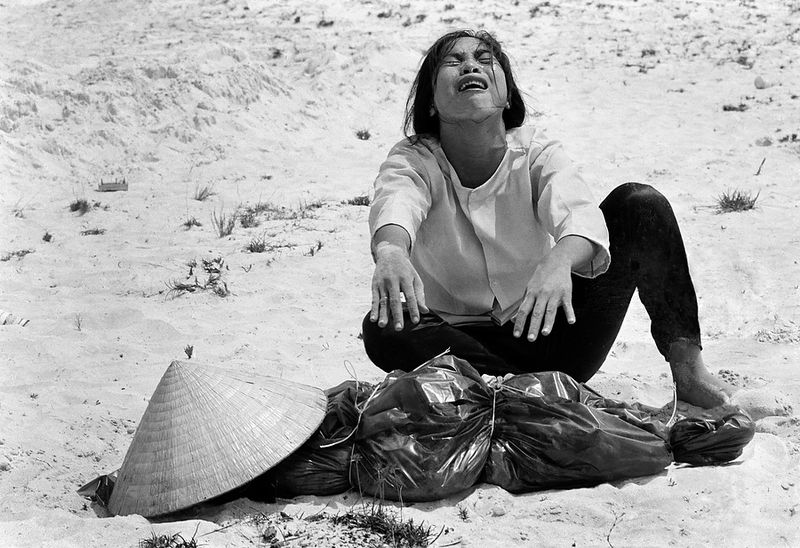

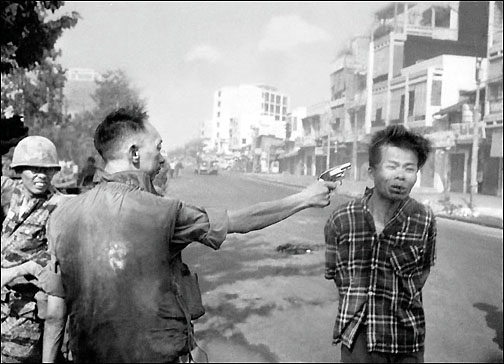

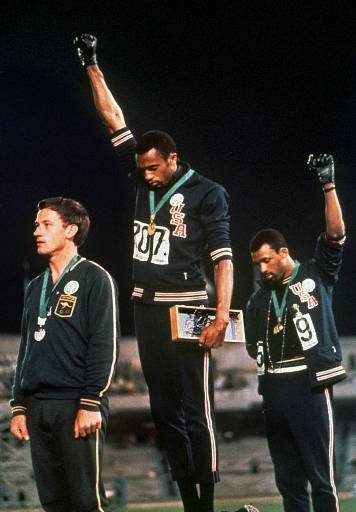

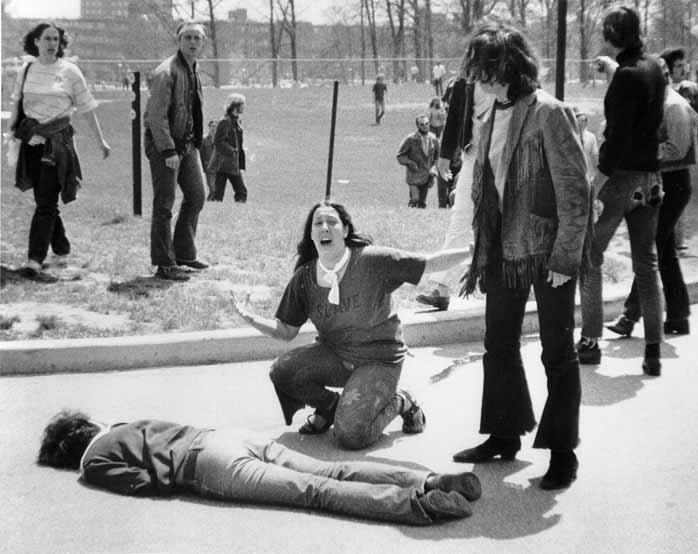

Today the New York Times featured Michael Kimmelman’s impassioned critique of the lack of public response to the carnage in Syria. “They keep coming, both the bombs and the images from Aleppo, so many of them.” The theme, and pathos, of the article is that while the bombs are effective, the images are not. Worse, they are not as effective as other images from previous catastrophes. Referring to photographs such as the Accidental Napalm icon from the Vietnam War, we are told that those images “drove news cycles for weeks, months, years, helping tip the scales of policy.”

The question naturally becomes, what’s wrong with us? The usual suspects are trotted out: bigotry, social media, and compassion fatigue not least among them. Well, sure, all of those factors could be in play, but once again photography is being framed.

Let’s start with the facts: First of all, coverage of the war in Syria–and the refugee crisis it has created–has motivated many governments and many individuals to help. Hundreds of millions of dollars in government and charitable aid have been supplied, and thousands have opened their doors around the world. The photographs probably had something to do with that. The fact that some of them are as recognizable as earlier icons attests to their likely contribution, as do many testimonials.

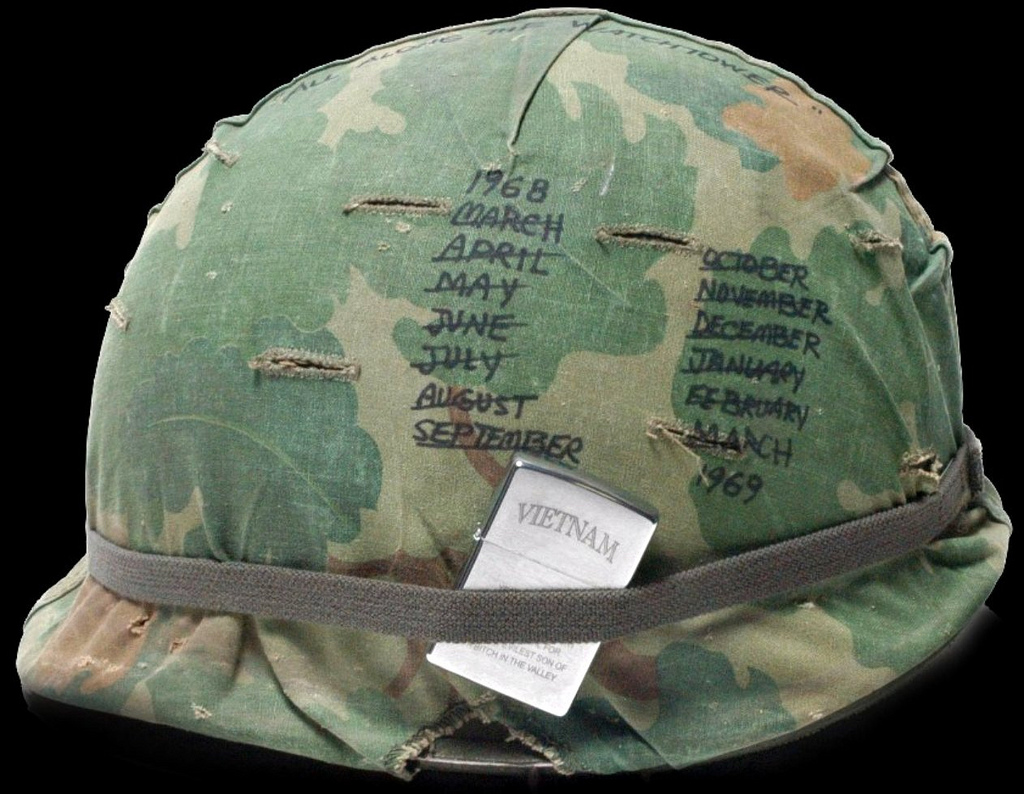

But they didn’t do it all, which gets to the next problem. Those great images from the past did not drive news cycles for years. Those of us who have studied iconic photographs have learned that their value does not depend on a direct causal effect. The news cycle moves on regardless, while the iconic images develop over time. (If they don’t persist, they aren’t iconic.) They come to have many uses and may have long wave influence, but they don’t end the war or the famine or otherwise stop history in its tracks.

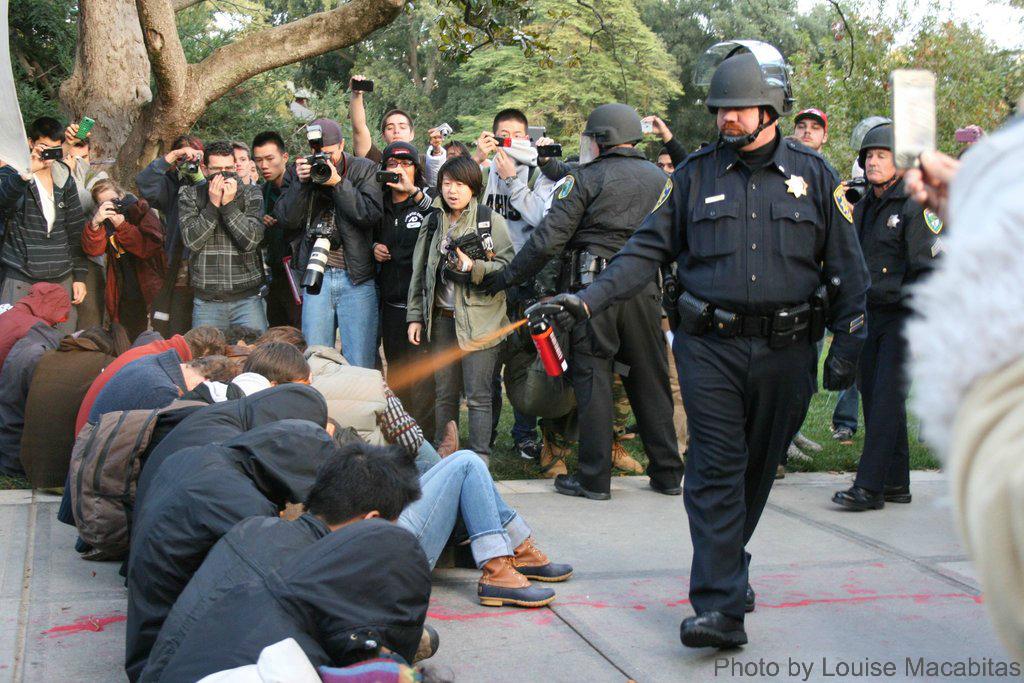

And neither does anything else, which gets to the next problem with the conventional critique of photography’s ineffectiveness. How many words have been written about Aleppo? How many articles and editorials and blog posts? How many special reports and pastoral letters and letters to the editor? Why don’t these texts have to bear the burden of ineffectiveness? They, too, are ephemeral, they don’t drive the news cycle for long periods of time, and although they bear witness they don’t provoke mass protests.

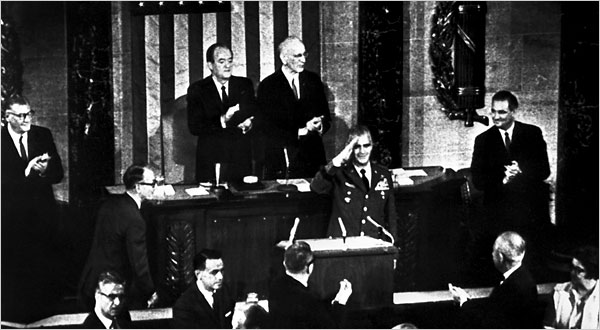

Nor does this mean that the public is hopelessly indifferent. As we’ve argued before (here and here), for anything to be persuasive, a lot has to be in place. A political process, just to take one example. The public has not been indifferent, it still has stores of compassion, we are perfectly capable of using social media and caring at the same time, and support from the bigots isn’t needed. But there have been massive failures of governance and diplomacy, and political leaders should be held accountable.

The catastrophe in Aleppo was not inevitable, and there still is great need to resolve the conflicts there and elsewhere in the region. Kimmelman is right about the most important things: We should feel horror and shame when watching the destruction of Aleppo. The public should demand help for those are displaced and destroyed by war, and for an end to the war. He also is wise in suggesting that an effective protest movement is likely to require “slow, brick by brick construction.” It always has–and those doing the killing can count on that. The problem is complex, and so many alternatives large and small need to be tried.

If social media can help as well, so much the better. If photographs can make a difference, we should be grateful we have them. But let’s not kid ourselves. The fault is not primarily in ourselves or in our media. Aleppo has been allowed to die, and while it has happened on our watch, those who are responsible have yet to be confronted.

UPDATE: Readers might want to see similar arguments set forth (in French) here and summarized here.

Cross-posted: a slightly adapted version is at Reading the Pictures.