Americans like to think that the world revolves around the U.S. For vivid demonstration of a different perspective, look at this photo, which is dated September 11, 2007:

The caption said, “German herders guide a decorated cow and other cattle Tuesday on the move from high alpine summer pastures to lower altitudes in the mountains near Bad Hindelang, in southern Germany.”

Even without the 9/11 date, this picture strikes me as uncanny. The bucolic scene could be from centuries ago, except for the state-of-the-art hiking boots, perfectly machined clothing, and farmers who obviously have never wanted for food, good health care, and all the other benefits of late-modern European civilization. The cow’s ornate decoration is equally incongruous, like something found in a tourist boutique Christmas Store rather than on modern livestock who are blessed (as these probably are) if they can stay out of a wretched feedlot. Above all, these are German herders, and the idea that they are part of the labor force of a modern, high-tech nation just doesn’t mesh with the incredibly relaxed, ambulatory slowness of the scene. They obviously are walking at a cow’s pace–for those of you who don’t know, that is really s l o w–and they are doing so easily, comfortably. While I was getting edgy waiting impatiently for a traffic light to turn green, these guys were ambling through a verdant alpine valley. And what little work they were doing by walking downhill was being made into ritualized play.

Whether acting out an invented tradition or authentic examples of the German volk, the incongruity is extended further by the boy in the foreground. While mountain people should be hardy, wild, and reclusive, he looks so open and gentle. Though likely to grow up like the physically impressive men behind him, he appears vulnerable, still formed in the soft clay of childhood. He is presented directly to the viewer as if we ought to take him in, and so the photograph suggests that this pastoral scene might become part of our world. The herders are walking into our space, perhaps to bring their green harmony with them.

That sense of peace seems a long way from 9/11 and the urban canyons of New York or Chicago, but there are sharper contrasts beyond that. This photograph appeared in the New York Times on September 13:

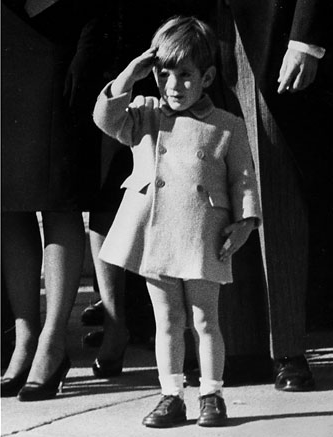

The story featured a sense of incongruity: “In Southern Sudan, Peace Alters a Way of Life.” Peace can do that, particularly when contrasted with rape, murder, starvation, forced migration, and other forms of terror that are never mentioned by the Times reporter. This picture isn’t about war, however, but about third world deprivation. The point of the story is that the Dinka way of life is becoming harder to sustain as young people are lured to the city. This boy is on the cusp: he herds the cattle, yet wears modern clothes. His indeterminate age symbolizes his indeterminate position: the caption informs us that his parents don’t know his age but guess he is about 11 or 12, i.e., about to enter the transition to adulthood. There are no adults in the picture, and the Western reader will conclude from the parent’s ignorance that they are either primitive or negligent, neither of which bodes well for a child caught between two worlds.

The photograph pushes this point. We are looking up at the boy as if he were in a position of power. But it is the wrong kind of power: he is a boy doing adult labor. This mismatch is reinforced by seeing his clothes come up short, by his sullen expression, and by the contrast with the open vista behind him. He is a capable herder but yoked to the cattle. His herding stick suggests the yoke and is matched by another stick protruding upwards to create an artificial border within the picture. The boy is already hardened by child labor in the desert and confined by the boundaries of his primitive society. (The benefits of living in this traditional society are no part of the story or the photograph.) Though revealing some of the incongruities of contemporary Dinka life, this photograph is not uncanny but rather one that makes reality seem hardened, depressing, and perhaps hopeless.

Two photographs, two boys herding cattle, two very different worlds on the same planet.

Photographs by Christof Stache/Associated Press, Evelyn Hockstein/New York Times.

1 Comment