President Obama’s declaration that we will remove all combat troops from Iraq by the end of 2010 is something of a moment for celebration (if leaving a country that we occupied and brought to its knees under false pretenses and is now caught in the throes of sectarian violence can be seen as a moment of joy), but the pleasure of that announcement has to be mitigated a good deal by the fact that he has also committed an additional 17,000 troops to the war in Afghanistan (on top of the 32,000 troops already there). Al Qaeda is ensconced in the caves and hills of the Afghanistan mountains and the Taliban does arguably pose a national security threat to the U.S., so this may be justified at some level, though whether it is a winnable war or not—or what a victory here would actually look like—are certainly open question (just ask the leaders of the former Soviet Union … if you can find any of them). But what is troubling is the way in which we seem to have convinced ourselves that the reason we having been fighting this war, at least in part, has been to save the women of Afghanistan.

To be sure, I have no doubt that the women of Afghanistan are treated in ways that are horribly inhumane and cannot possibly be justified in any way by appeals to cultural differences or long standing traditions. But there is a continuing and nagging cultural meme that presumes to justify U.S. military presence in Afghanistan as somehow connected to securing the human right of these women. It’s not part of the official rationale for our being there as far as I know, though I do recall Laura Bush making such a public appeal a few years back, but the concept nevertheless seems to float along within the public discourse in a network of vaguely connected narratives and cultural associations that functions as a sort of moral imperative for our presence there; and here’s the point: it does this in a way that distracts attention from the larger public debate we should be having about our national interests and concerns in this part of the world and how we should go about accomplishing them.

The presence of this meme was given visual prominence this past week on the front page of the NYT as part of a story (and a website slide show) dedicated to the idea that talk of women’s rights in Afghanistan is starting to take hold and with the clear implication that it is a direct effect of the U.S. defeat of the Taliban in 2001. The photograph is of a seventeen year old woman by the name of Mariam, who had been forced to marry a forty-one year old blind man at the age of eleven and was then beaten and otherwise abused because she failed to conceive. She eventually fled and found refuge in a woman’s shelter

The narrative is full of pathos, and one would have to be cold hearted not to be deeply affected by it, but what distinguishes it from numerous other such stories one can find on the internet is the image that anchors the report, a photograph that bears distinct resemblance to the photograph of the now famous “Afghan Girl” that graced the cover of National Geographic in 1985 and again in 2002, and has been a persistent sign of U.S. concern for the plight of women and war refugees caused by the Soviet aggression. And so instead of focusing attention on the fact that we will increase our military presence in Afghanistan to nearly 60,000 troops, we are encouraged to a state of self-satisfaction in the knowledge that we have somehow done better than the evil empire that preceded us in a war that seems never to end.

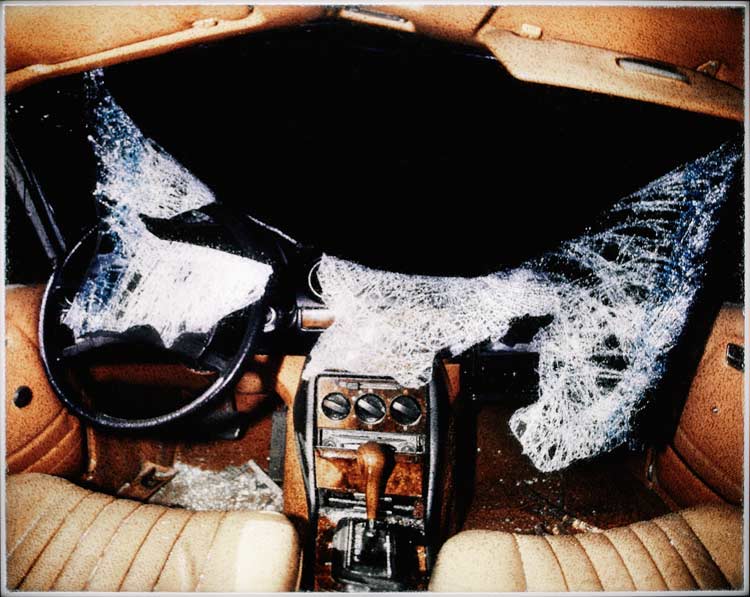

But there is more. For one week earlier the NYT reported on the plight of Iraq’s war widows. According to the United Nations 10 percent of all Iraqi women aged 15 to 80 are widowed—740,000 in all—and without the resources to sustain themselves, often forced to resort to begging, prostitution, or “temporary marriages” required to procure even a modicum of state support. Many if not most of these women were widowed by sectarian violence unleashed by the U.S. invaston and at least some—there is no way of knowing exactly how many—have lost their families to American gunfire and missile attacks, such as Nacham Jaleel Kadim, age 23, pictured below who lost both her twin sisters and her husband.

If we are truly concerned about the plight of women in the Islamic world perhaps we should start here.

Photo Credit: Lynsey Addano and Johan Spanner for the New York Times